Concepts

- there are two benefits of multithreading - responsiveness and performance

- repeat - remember multithreading gives both the features above

- concurrency means performing different tasks on the same core. instead of waiting for one task to entirely complete first, we perform both simultaneously in a time-shared manner. it increases responsiveness

- concurrency is also called multi tasking. remember - we do not even need different cores for this

- parallelism means performing different tasks on different cores. it increases performance

- throughput is the number of tasks completed per unit time

- latency is the time taken per unit task

- how are the two different

- for optimizing throughput, since the tasks themselves are different, they just need to be scheduled on different threads in parallel, and that automatically increases the throughput. therefore, fewer considerations exist

- for optimizing latency, we would probably break a single task into smaller subtasks. considerations -

- what parts of the original task can be performed in parallel and which parts have to be done sequentially

- how to aggregate the smaller chunks of results into the final result

- in case of multithreading, components like heaps get shared across the threads, while components like stack and instruction pointer are scoped to a single thread

- what is stored inside the stack -

- local primitive types, e.g. if we declare an

int a = 1inside a method - primitive formal parameters - similar to above -

int add(int a, int b) - references created inside functions are stored in stack

- local primitive types, e.g. if we declare an

- what is stored inside the heap -

- all the objects (not references) are stored in heap

- members of a class - primitive values and non primitive references - should be stored in heap - note how these when declared inside functions are stored in stacks as discussed above

- ideally this makes sense - remember, each thread is executing a different instruction, so each of them needs its own instruction pointer etc

- a frame is created for every method call - this way, when a method gets over, it is popped off from the stack - last in first out - main method gets popped of last from the stack

- a lot of frames in the stack can result with a stack overflow exception if we end up with too many frames

- heap belongs to a process, and all threads can write to / read from the heap at any given time

- all objects are stored in the heap till there is a reference to them, after which they get garbage collected by the garbage collector

- note - we can write

System.gc(), which hints the jvm to run this garbage collector - strength of java is this automatic memory management, which we do not have to worry about

- when we execute a program, it becomes a process i.e. it gets loaded into the memory from the disk and a thread is used to execute it

- there are often way more processes being executed than cores in a cpu. so, using context switching, one thread at a time gets cpu and, gets paused and another thread is scheduled on the cpu

- context switching has overhead, and doing a lot of it can lead to something called thrashing

- however, context switching between the threads of the same process is much cheaper than context switching between the threads of different processes, since a lot of components like heaps are reused

- when the operating system has to chose between scheduling multiple tasks on a thread, and if for e.g. it schedules a computationally expensive task first, it can lead to the starvation of other smaller tasks

- so, to combat issues like this, there are various algorithms used by the operating system to calculate the priority of a task

- we can also programmatically provide a priority which gets used in the calculation above

- a thing that struck me - when writing applications, do not base your conclusions off the computer you are running your code on, base it off how it would work on the server

- number of threads = number of cores is the best way to start, since context switching as discussed earlier consumes resources

- however, it is only optimal if the threads are always performing some computation, and never in blocked state. if the threads perform some io, then a thread performing some computation can take its place

- also, modern day computers use hyper threading i.e. the same physical core is divided into multiple virtual cores. this means that a core can run more than one thread in modern cpus

Thread Creation

- we create an instance of

Threadand to it, we pass an object of a class that implementsRunnable. itsrunmethod needs to be overridden. all of this can be replaced by a lambda java 8 onwardsThread thread = new Thread(() -> System.out.println("i am inside " + Thread.currentThread().getName())); thread.start(); - if instead of using

Runnable, we extend theThreadclass, we get access to a lot of internal methods - when we run

Thread.sleep, we instruct the os to not schedule that thread until the timeout is over - note misconception - invoking this method does not consume any cpu i.e. it is not like a while loop that waits for 5 seconds

- we can set a name of a thread to make it helpful when debugging, using

thread.setName() - we can set a priority between 1 and 10 using

thread.setPriority - we can use

thread.setUncaughtExceptionHandlerto catch “unchecked exceptions” that might have occurred during the execution of the thread, and thus cleanup resources - we can shut down the application entirely from any thread using

System.exit(0)

Thread Coordination

- the application will not terminate until all threads stop

- but, we might want to interrupt a thread so that the thread can maybe understand that the application wants to terminate, and accordingly handle cleaning up of resources

Thread thread = new Thread(new Task()); thread.start(); thread.interrupt(); - the interruption can be handled gracefully in two ways as described below

- if our code throws an interrupted exception, calling

interruptwill trigger it, and then we can handle it. other examples where this exception happens are for calls likethread.join()andobject.wait()public class Task implements Runnable { @Override public void run() { try { Thread.sleep(20000); } catch (InterruptedException e) { System.out.println("[inside catch] i was interrupted..."); } } } - else we can check the property

isInterruptedand handle it accordinglypublic class Task implements Runnable { @Override public void run() { Date date = new Date(); while ((new Date()).getTime() - date.getTime() < 10000) { if (Thread.currentThread().isInterrupted()) { System.out.println("[inside loop] i was interrupted..."); break; } } } }

- if our code throws an interrupted exception, calling

- background / daemon threads there might be a case when what the thread does need not be handled gracefully, and it is just an overhead for us to check for e.g. the

isInterruptedcontinually. so, we can set the daemon property of the thread to true. this way when the thread is interrupted, it will be terminated without us having to handle itThread thread = new Thread(new Task()); thread.setDaemon(true); thread.start(); thread.interrupt(); - also, unlike normal threads, where the application does not close if any thread is running, a daemon thread does not prevent the application from terminating

- if we implement

Callableinstead ofRunnable, we can also throw anInterruptedExceptionwhen for e.g. we see thatisInterruptedis evaluated to true. this means the parent thread calling this thread will know that it was interrupted in an adhoc manner - threads execute independent of each other. but what if thread b depends on the results of thread a?

- busy wait - one way could be we run a loop in thread b to monitor the status of thread a (assume thread a sets a boolean to true). this means thread b is also using resources, which is not ideal

- so, we can instead call

threadA.join()from thread b, thread b goes into waiting state till thread a completes - we should also consider calling the join with a timeout, e.g.

threadA.join(t) - my understanding - if for e.g. the main thread runs the below. first, we start threads t1 and t2 in parallel of the main thread. now, we block the main thread by calling

t1.join(). the main thread will be stopped till t1 completest1.start(); t2.start(); t1.join(); t2.join(); - scenario 1 - t1 completes before t2, the main thread resumes, and again will be stopped till t2 completes

- scenario 2 - t1 completes after t2. the main thread resumes and will not wait for t2 since it has already completed

Thread Pooling

- thread pooling - reusing threads instead of recreating them every time

- tasks are added to a queue, and the threads pick them up as and when they become free

- so, when tasks are cpu intensive, we should have number of threads closer to core size, and when tasks are io intensive, we should have higher number of threads, but remember that -

- too many threads can cause performance issues as well due to context switching

- threads are not trivial to create, they are resource intensive

- java provides 4 kinds of thread pools -

FixedThreadPool,CachedThreadPool,ScheduledThreadPoolandSingleThreadedExecutor - fixed thread pool executor - polls for tasks stored in a queue. there can be many tasks, but a set number of threads which get reused. the queue should be thread safe i.e. blocking

int numberOfProcessors = Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors(); ExecutorService executorService = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(numberOfProcessors); executorService.execute(new Runnable() {...}); - cached thread pool executor - it looks at its threads to see if any of them are free, and if it is able to find one, it will schedule this task on the free thread. else, it will spawn a new thread. too many threads is not too big of a problem, thanks to the keep alive timeout discussed later. however, expect out of memory exceptions if too many tasks are added to the executor, because threads are resource intensive

ExecutorService executorService = Executors.newCachedThreadPool(); - to remember - threads occupy a lot of space in main memory, hence can cause out of memory exceptions if not controlled properly

- scheduled thread pool executor - it used a delay queue, so that the tasks get picked up by the threads after the specified delay or schedule. this means tasks might have to be reordered, which is done by the queue itself.

schedulecan help trigger the task after a certain delay,scheduleAtFixedRatecan help trigger it like a cron at regular intervals whilescheduleAtFixedDelaycan help schedule the next task a fixed time period after the previous task was completedScheduledExecutorService executorService = Executors.newScheduledThreadPool(5); executorService.schedule( () -> System.out.println("hi from " + Thread.currentThread().getName()), 5, TimeUnit.SECONDS ); - single thread pool executor - like fixed thread pool executor with size of pool as one. the advantage is for e.g. all the tasks will be run in order of creation

- all thread pool executors create new threads if the previous thread is killed for some reason

- there are a variety of parameters that can be added to the executors

- core pool size - minimum number of threads that are always kept in the pool

- max pool size - maximum number of threads that can be present in the thread pool. it has value

INTEGER.MAX_VALUEby default for cached and scheduled thread pool executor, while the same value as core pool size for fixed and single thread pool executor - keep alive timeout - the time till an idle thread is kept in the pool, after which it is removed. keep alive is only applicable to cached and scheduled thread pool executors, since in fixed and single thread pool executors, the number of threads do not change

- note that keep alive timeout does not change the core pool threads. this behavior can however be changed using

allowCoreThreadTimeOut - queue - the different types of executors use different queues based on their requirements. the queues also need to be thread safe

- e.g. a fixed and single thread pool executor has a fixed number of threads, so there can potentially be infinite number of tasks that get queued up, because of which it uses a

LinkedBlockingQueue - cached thread pool spawns number of threads equal to the number of tasks, so it uses a

SynchronousQueue, which only needs to hold one task - scheduled thread pool uses

DelayedWorkQueueso that the tasks are returned from the queue only if the condition of cron etc. is met

- e.g. a fixed and single thread pool executor has a fixed number of threads, so there can potentially be infinite number of tasks that get queued up, because of which it uses a

- rejection handler - assume all threads are occupied and the queue is full. in this case, the thread pool will reject the task that it gets. how it rejects the task is determined using the rejection policy. the different rejection policies are -

- abort - submitting the new task throws

RejectedExecutionException, which is a runtime exception - discard - silently discard the incoming task

- discard oldest - discard the oldest task from the queue to add this new task to the queue

- caller runs - requests the caller thread itself to run this task

- abort - submitting the new task throws

- till now, to obtain an instance of

ExecutorService, we were using static methods onExecutors. we can also usenew ThreadPoolExecutor()and then pass our own core pool size, queue, etc. configuration parameters as the constructor arguments - we need to shut down the executor in a clean way. we can initiate it using

executorService.shutdown(). this will throw theRejectedExecutionExceptionfor any new tasks that are submitted to it, but at the same time will complete both all the currently executing tasks and queued up tasks - if we run

shutdownNow, it will returnList<Runnable>for the queued up tasks and clear the queue, but complete all the currently executing tasks awaitTermination(timeout)will terminate the tasks if they are not completed by the specified time- we also have helper methods like

isShutdown()andisTerminated() - if a task wants to return a value, we use

Callableinstead ofRunnable - however, the

executemethod onExecutorServiceonly works if we implementRunnableinterface. if we implementCallableinterface, we have to usesubmit - the return value of

Callableis wrapped around aFuture.future.get()is a blocking call i.e. the thread calling it will not move ahead until the future resolves. so, we can also usefuture.get(timeout)ExecutorService executorService = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(1); Future<Integer> result = executorService.submit(() -> { Thread.sleep(4000); return (new Random()).nextInt(); }); Thread.sleep(3000); // this simulates that we were able to perform 3 seconds worth of operations // in the main thread while the task thread was performing its blocking stuff System.out.println("result = " + result.get()); - we can cancel the task using

future.cancel(false). this means that the thread pool will remove the task from the queue. the false means that if a thread is already running the task, it will not do anything. had we passed true, it would have tried to interrupt the task - we also have helper methods like

future.isDone()andfuture.isCancelled() - suppose we have a list of items, and for each item, we want to perform a series of processing

Future<Package> package$ = executorService.submit(() -> pack(order)); Future<Delivery> delivery$ = executorService.submit(() -> deliver(package$.get())); Future<Email> email$ = executorService.submit(() -> sendEmail(delivery$.get()));notice how the calling thread is blocked by all

getof future. instead, we could use -CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> pack(order)) .thenApply((package) -> deliver(package)) .thenApply((delivery) -> sendEmail(delivery)) // ... - in the above case, we have specified a series of steps to run one after another and since we do not care about the results in our main thread, the assigning of tasks to threads is managed by java itself. the main thread is not paused by the get calls. notice how we also do not need to specify any executor

- if we use

thenApplyAsyncinstead ofthenApply, a different thread can be used to execute the next operation instead of the previous one - internally,

CompletableFutureuses fork join pool, but we can specify a custom executor as well, e.g.thenApplyAsync(fn, executor)

Race Condition

- race condition - happens where resource is shared across multiple threads

public class SharedResourceProblem { public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception { Integer count = 10000000; Counter counter = new Counter(); Thread a = new Thread(() -> { for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) { counter.increment(); } }); Thread b = new Thread(() -> { for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) { counter.decrement(); } }); a.start(); b.start(); a.join(); b.join(); System.out.println("shared resource value = " + counter.getCount()); // shared resource value = 15 } } class Counter { private int count = 0; public void increment() { count += 1; } public void decrement() { count -= 1; } public int getCount() { return count; } } - the

resource += 1andresource -= 1operations are not atomic, it comprises of three individual operations -- getting the original value

- incrementing it by one

- setting the new value

- solutions - identify critical sections and use locks, make operations atomic, etc

Synchronized

- we can wrap our code blocks with a critical section, which makes them atomic. this way, only one thread can access that block of code at a time, and any other thread trying to access it during this will be suspended till the critical section is freed

- say we use

synchronizedon multiple methods of a class - once a thread invokes one of the synchronized method of this class, no other thread can invoke any other synchronized method of this class. this is because using synchronized on a method is applied on the instance (object) of the method

- the object referred to above is called a monitor. only one thread can acquire a monitor at a time

- method one - prefix method signature with synchronized (refer the counter example earlier. the shared resource print would now print 0)

public synchronized void increment() { // ... } - another method is to use synchronized blocks

synchronized (object) { // ... } - using blocks, the code is much more flexible since we can have different critical sections locked on different monitors

- if using synchronized on methods, two different methods of the same class cannot be executed in parallel - the monitor there is the instance itself

- however, when using synchronized blocks, we can do as follows inside different methods of the same class -

Object lock1 = new Object(); Object lock2 = new Object(); // ... synchronized(lock1) { // ... } synchronized(lock2) { // ... } - note - reduce critical section size for better performance

Atomic Operations

- so, assignment to references and primitive values in java are atomic

this.name = nameinside for e.g. a constructor is atomicint a = 8is atomic

- however, an exception in this is assignment to longs and doubles. since it is 64 bit, it happens in 2 operations - one assignment for the lower 32 bit and another one for the upper 32 bit

- the solution is to declare them with volatile, e.g.

volatile double a = 1.2 - using volatile makes operations on longs and doubles atomic

- also, java has a lot of atomic classes under

java.util.concurrent.atomicas well - remember - when we use volatile, we make assignment atomic, not operations like

a++atomic - my doubt probably cleared - then what is the use for e.g.

AtomicReference, if assignment to reference is already an atomic operation? we can do as follows (a metric example discussed later)AtomicReference<State> state$ = new AtomicReference<>(); state$.set(initialValue); State currentState = state$.get(); State newSate = computeNewState(); Boolean isUpdateSuccess = state$.compareAndSet(currentState, newState);

Data Race

- remember - race condition and data race are two different problems

- data race - when the order of operations on variables do not match the sequential code we write. this happens mostly because there are optimizations like prefetching, vectorization, rearranging of instructions, etc

class Pair { private int a = 0; private int b = 0; public void increment() { a++; b++; } public void check() { if (b > a) { System.out.println("well that doesn't seem right..."); } } }calling the class -

Pair pair = new Pair(); Thread t1 = new Thread(() -> { while (true) pair.increment(); }); Thread t2 = new Thread(() -> { while (true) pair.check(); }); t1.start(); t2.start(); t1.join(); t2.join(); - our expectation is that since b is read before a and a is incremented before b, there is no way even with a race condition that b can be bigger than a. however, due to data race, we do hit the print statement

- data race is also where we can use

volatile. volatile guarantees the order of instructions being executedprivate volatile int a = 0; private volatile int b = 0; - this is called the visibility problem

- basically, the two threads have their own local cache, but also have a shared cache. they write the value to the local cache, but this does not

- either update the shared cache

- or the second thread’s local cache does not refresh its value from the shared cache

- however, when we use volatile, it refreshes / synchronizes both the shared cache and the local cache of all threads

- basically, code before access to a volatile variable gets executed before it, and code after the access to a volatile variable after. this is called the happens before relationship

- while we could have just used synchronized for both the methods above, realize the advantage of using volatile over synchronized. with synchronization, we lose out on the multithreading, since our functions would have been invoked one at a time. in this case, the two methods are still being invoked concurrently

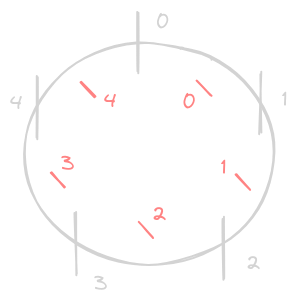

- if we have n cores, for each core we have a register. then we have an associated l1 cache on top of each register. l2 cache can be shared across multiple cores, and finally we have only one l3 cache and ram

![multithreading]()

- java memory model - it is an enforcement that jvm implementations have to follow so that java programs have similar behavior everywhere, and the different optimizations of instructions, cache, etc. do not affect the functioning of the program

Locking Strategies and Deadlocks

- coarse-grained locking - meaning we use one lock for everything, just like having synchronized on all methods, not performant. its counterpart is fine-grained locking

- coarse grained locking example - make all methods of the class synchronized

- cons with fine-grained locking - we can run into deadlocks more often

- conditions for a deadlock -

- mutual exclusion - only one thread can hold the resource at a time

- hold and wait - the thread acquires the resource and is waiting for another resource to be freed up

- non-preemptive - the resource is released only when the thread is done using it and another thread cannot acquire it forcefully

- circular wait - a cyclic dependency is formed where threads wait for resources acquired by each other

- one way to prevent deadlocks is to acquire locks in our code in the same order. this need not be considered when releasing the locks

- another way can be to use techniques like

tryLock,lockInterruptibly, etc (discussed later) - reentrant lock - instead of having a synchronized block, we use this reentrant lock

Lock lock = new ReentrantLock(); - unlike synchronized where the block signals the start and end of the critical section, locking and unlocking happens explicitly in case of reentrant locks

- to avoid deadlocks caused by for e.g. the method throwing exceptions, we should use it in the following way -

lock.lock(); try { // critical section } finally { lock.unlock(); } - it provides a lot of methods for more advanced use cases like

getOwner,getQueuedThreads,isHeldByCurrentThread,isLocked, etc - the name

Reentrantcomes from the fact that the lock can be acquired by the thread multiple times, which means it would have to free it multiple times as well, e.g. think about recursive calls. we can get the number of times it was acquired usinggetHoldCount - another benefit of using reentrant locks is fairness - e.g. what if a thread repeatedly acquires the lock, leading to the starving of other threads? we can prevent this by instantiating it using

new ReentrantLock(true) - note that introducing fairness also has some overhead associated with it, thus impacting performance

- if we do not set to true, what we get is a barge in lock i.e. suppose there are three threads waiting for the lock in a queue. when the thread originally with the lock releases it, if a new thread not in the queue comes up to acquire the lock, it gets the lock and the threads in the queue continue to stay there. however, if we had set the fairness to true, the thread with the longest waiting time gets it first

- so, two problems - “fairness” and “barge in lock” are solved by reentrant lock

- if the lock is not available, the thread of course goes into the suspended state till it is able to acquire the lock

- we can use

lockInterruptibly- this way, another thread can for e.g. callthis_thread.interrupt(), and an interrupted exception is thrown. this “unblocks” the thread to help it proceed further. had we just used lock, the wait would have been indefinitetry { lock.lockInterruptibly(); } catch (InterruptedException e) { // cleanup and exit } - similar to above, we also have the

tryLockmethod, which returns a boolean that indicates whether a lock was successfully acquired. it also accepts timeout as a parameter, what that does is self-explanatory - this can help, for e.g. in realtime applications to provide feedback continuously without pausing the application entirely

while (true) { if (lock.tryLock()) { try { // critical section } finally { lock.unlock(); } } else { // some logic } // some logic } - so, we saw how reentrant lock, which while works like synchronized keyword, has additional capabilities like telling current owner and locking using different strategies like

lockInterruptiblyandtryLock - when locking till now, we used mutual exclusion to its fullest. but, we can be a bit more flexible when the shared resource is just being read from and not written to

- multiple readers can access a resource concurrently but multiple writers or one writer with multiple readers cannot

- this is why we have

ReentrantReadWriteLockReentrantReadWriteLock lock = new ReentrantReadWriteLock(); Lock readLock = lock.readLock(); Lock writeLock = lock.writeLock(); - fairness in

ReentrantReadWriteLockworks the same way asReentrantLock, except that if the thread waiting for the longest time was a reader, all reader threads in the queue are freed up to read - of course, base decisions off of type of workloads - if workload is read intensive, read write lock is better, otherwise we might be better off using the normal reentrant lock itself

Inter Thread Communication

- semaphore - it helps restrict number of users to a resource

- remember - locks only allow one user per resource, but semaphores allow multiple users to acquire a resource

- so, we can call a lock a semaphore with one resource

Semaphore semaphore = new Semaphore(number_of_permits); - when we call

semaphore.acquire()to acquire a permit, and the number of permits reduces by one. if no permits are available at the moment, the thread is blocked till a resource in the semaphore is released - similarly, we have

semaphore.release() - optionally, i think both

acquireandreleaseaccept n, the number as an argument which can help acquire / release more than one permit - another major difference from locks - there is no notion of owning thread in semaphores unlike in locks - e.g. a semaphore acquired by thread a can be released by thread b. so, thread a can acquire it again without having ever released it

- this reason also makes semaphores are a great choice for producer consumer problems. producer consumer problem using semaphores -

- we need a lock so that multiple threads cannot touch the queue at one go

- we start with the full semaphore being empty and the empty semaphore being full, since there are no items initially

- look how we use semaphore’s philosophy to our advantage - consumer threads acquire full semaphore while producer threads release it

- my understanding of why we need two semaphores - e.g. if we only had full semaphore - producer releases it and consumer acquires it - how would we have “stopped” the producer from producing when the rate of production > rate of consumption? its almost like that the two semaphores help with back pressure as well

Integer CAPACITY = 50; Semaphore empty = new Semaphore(CAPACITY); Semaphore full = new Semaphore(0); Queue<Item> queue = new ArrayDeque<>(CAPACITY); Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

- producer code -

while (true) { empty.acquire(); Item item = produce(); lock.lock(); try { queue.add(item); } finally { lock.unlock(); } full.release(); } - consumer code -

while (true) { full.acquire(); Item item; lock.lock(); try { item = queue.poll(); } finally { lock.unlock(); } consume(item); empty.release(); } - some different inter thread communication techniques we saw till now -

- calling

interruptfrom one thread on another thread. this is then further used in techniques likelockInterruptibly - calling

joinfor a thread to wait for another thread to complete its job - using

acquireandreleaseon semaphore

- calling

- conditions flow -

- one thread checks a condition, and goes to sleep if the condition is not met

- a second thread can “mutate the state” and signal the first thread to check its condition again

- if the condition is met, the thread proceeds, else it can go back to sleep

- note - conditions come with a lock, so that the “state” being modified can be wrapped with a critical section

- note - when we call

awaiton the condition, it also releases the lock before going to sleep, so that the second thread described in the flow above can acquire the lock to mutate the state. so, even though the thread which was waiting gets signaled to wake up, it also needs to be able to acquire the lock again, i.e. the other threads modifying state need to release the lock - placing the condition inside the while loop helps so that even if signalled, it will again start waiting if the condition is not met yet

- first thread -

ReentrantLock lock = new ReentrantLock(); Condition condition = lock.newCondition(); lock.lock(); try { while (condition x is not met) { condition.await(); } } finally { lock.unlock(); } - second thread -

lock.lock(); try { // modify variables used in condition x... condition.signal(); // despite signalling, thread one does not wake up, we need to unlock the lock first } finally { lock.unlock(); }

- conditions also have advanced methods like -

await(timeout)- just like locks have timeouts to prevent indefinite waitingsignalAll- usingsignal, only one of all the threads waiting on the condition wake up,signalAllwakes all of them up

- the class Object, and therefore all objects have methods

wait,notifyandnotifyAll - therefore, without using any special classes -

- simulate conditions using

wait,notifyandnotifyAll - simulate locks using

synchronized

- simulate conditions using

- note - recall how when using conditions we were wrapping it via locks. we need to do the same thing here i.e. wrap using synchronized block in order to be able to call notify

- first thread -

synchronized (this) { while (condition x is not met) { wait(); } } - second thread. my understanding - but needs to happen on same object and inside different method -

synchronized(this) { // modify variables used in condition x... notify(); }

- first thread -

- when we call

waiton an object, the thread it was called on continues to be in waiting state until another thread callsnotifyon that object notifywill wake up any random thread that was sleeping, and to wake up all threads we can usenotifyAll- note, important, my understanding - the order of operations should not matter i.e. calling

notifyvs changing of state - because everything is inside a critical section, inside the same monitor - if we think about it, the

lock.lock()andlock.unlock()are the starting and ending ofsynchronizeblocks respectively,condition.await()is likewait()andcondition.signal()likenotify() - introducing locks can make our code more error-prone, more subject to deadlocks etc. however, it makes the code more flexible, e.g. unlike synchronized blocks which have to exist within a single method, locks can be acquired and freed from different methods

- using locks result in issues like deadlocks if coded improperly

- our main objective is to execute instructions as a single hardware operation

- we can achieve this by using Atomic classes provided by java

AtomicInteger count = new AtomicInteger(initialValue); count.incrementAndGet(); - recall how we had discussed that

a = a + 1actually consisted of three atomic operations, which has all been condensed down into one using these java helper classes - so, recall the counter example in shared resource earlier, and how we had solved it using synchronized. we can now get rid of the

synchronizedand implement it as follows -public void increment() { count.incrementAndGet(); } - the disadvantage of using these classes is of course that only each operation by itself is atomic, a series of such calls together is not atomic, so it may be good only for simpler use cases

- a lot of operations use

compareAndSetunderneath, and we have access to it to. it sets the value to the new value if the current value matches the expected value. otherwise, the old value is retained. it also returns a boolean which is true if the current value matches the expected valuecount.compareAndSet(expectedValue, newValue); AtomicReferencecan be used for any object type to get and set values in a thread safe i.e. atomic way, and we can use methods like compareAndSet on it- e.g. notice how below, the synchronized keyword is not used for addSample, but we still have a thread safe implementation by using

compareAndSet. note how and why we use a loop - if the old value stays the same before and after calculating the new value, then update using the new value, else recalculate using the new value using the “new old value”class Metric { int count = 0; int sum = 0; } class MetricAtomic { AtomicReference<Metric> metric$ = new AtomicReference<>(new Metric()); public void addSample(int sample) { Metric currentMetric; Metric newMetric; do { currentMetric = metric$.get(); newMetric = new Metric(); newMetric.count = currentMetric.count + 1; newMetric.sum = currentMetric.sum + sample; } while (!metric$.compareAndSet(currentMetric, newMetric)); } } - we often have a lot of tasks but not so many threads. some objects are not thread safe i.e. cannot be used by multiple threads. however, they can be used by multiple tasks being executed on the same thread. coding this ourselves can be tough, which is why we have

ThreadLocal, which basically returns a new instance for every thread, and reuses that instance when a thread asks for that instance againpublic static ThreadLocal<Car> car = ThreadLocal.withInitial(() -> new Car()); - spring uses the concept of this via

ContextHolders in for instance,RequestContextHolder,TransactionContextHolder,SecurityContextHolder, etc. my understanding - since spring follows one thread per-request model, this way, any of the services, classes, etc. that need access to information can get it easily. it is like setting and sharing state for a request

High Performance IO

- what is blocking io - when cpu is idle, e.g. when reading from database etc

- such io bound tasks block the thread till they return the result

- io bound tasks are very common in web applications etc

- how it works internally -

![io bound]()

- the controllers like network cards return the response to the dma (direct memory access)

- the dma writes it to the memory

- the dma notifies the cpu that the response is available

- the cpu can now access the memory for variables

- so, during this entire duration, the thread that was processing the request that involved the io task (and thus reaching out to the controller) was sitting idle and thus was blocked

- this is why number of threads = number of cores does not give us the best performance when we have more io bound instead of cpu intensive tasks

- this is why we have a “thread per request model” in spring mvc, which i believe caps at 200 threads to prevent out of memory errors etc

- it has caveats like -

- creating and managing threads are expensive - recall how it has its own stack etc

- number of context switching increases, which too is an expensive operation - recall thrashing

- assume that there are two kinds of calls a web server supports - one that makes a call to an external service and one that calls the database. assume the external service has a performance bug, which makes the first call very slow. this way, if we had for e.g. 150 requests for first call and 150 for the second call (assume 200 is the default thread pool size in embedded tomcat), the 150 instances of the second call would start to be affected because of the 150 instances of the first call now

- so, the newer model used by for e.g. spring web flux is asynchronous and non blocking

- the thread is no longer blocked waiting for the response - a callback is provided which is called once the request is resolved

- so now, we can go back to the thread per core model - which is much more optimal

- there can be problems like callback hell etc, which is solved by using libraries like project reactor for reactive style of programming, which is more declarative to write

Virtual Threads

- till now, the

Threadclass we saw was actually a wrapper around an actual os thread - these are also called platform threads - since they map one to one with os threads

- virtual threads - they are not directly related to os threads. they are managed by the jvm itself

- this makes them much less resource intensive

- the jvm manages a pool of platform threads, and schedules the virtual threads on these platform threads one by one

- once a virtual thread is mounted on a platform thread, it is called a carrier thread

- if a virtual thread cannot progress, it is unmounted from the platform thread and the platform thread starts tracking a new virtual thread

- this way, the number of platform threads stay small in number and are influenced by the number of cores

- there is no context switching overhead just like in reactive programming - what we are saving on here - frequent normal (hence platform hence os threads) context switching is replaced by frequent virtual thread context switching

- creation techniques -

Runnable runnable = () -> System.out.println("from thread: " + Thread.currentThread()); new Thread(runnable).start(); // platform thread (implicit) // from thread: Thread[#19,Thread-0,5,main] Thread.ofPlatform().unstarted(runnable).start(); // platform thread (explicit) // from thread: Thread[#20,Thread-1,5,main] Thread.ofVirtual().unstarted(runnable).start(); // platform thread // from thread: VirtualThread[#21]/runnable@ForkJoinPool-1-worker-1 - note - virtual threads are only useful when we have blocking io calls, not when we have cpu intensive operations

- this happens because unlike the usual model where our thread had to sit idle for the blocking call, the platform thread never stops here and is always working, it is the virtual thread that is sitting idle, and hence we optimize our cpu usage because we are using our platform threads optimally

- so, developers still write the usual blocking code, which simplifies coding, as compared to say reactive programming

- underneath, the blocking calls have been refactored for us to make use of virtual threads so that the platform threads are not sitting idle

- e.g. cached thread pools replacement is new virtual thread per task executor - we do not have to create pools of fixed size - we use a thread per task model and all the complexity is now managed by jvm for us bts

- when we are using normal threads for blocking calls e.g. using jpa, the thread cannot be used. what we can do is use context switching to utilize the cpu better. however, this model meant we needed a lot of platform threads, and managing them, context switching between them, etc has a lot of overhead, which is why maybe embedded tomcat for instance had a cap of about 200 threads. now with virtual threads, there is no cap needed, so it can be used via cached thread pool executor equivalent, but here there would never be any out of memory etc issues like in cached thread pool executor, since virtual threads are very lightweight

- some notes -

- virtual threads are always daemon, and making them non daemon will throw an exception

- virtual threads do not have a concept of priority

Miscellaneous Notes

- io bound threads are prioritized more than computation based threads

- since most of the time of ios threads is spent in waiting state

- and most of the time of cpu bound threads is spent in computation

- maybe this is related to concepts of starvation etc somehow

- why context switching is expensive - the entire state of the thread has to be saved in memory - all the stack, instruction pointer, local variables inside the method, etc

- thread yield - helps hint to the scheduler that the current thread wants to give up its processor

- can be used by computationally expensive threads to hint the scheduler that they want to give up the processor for another thread

- the priority we set manually only serves as a hint - the os can choose to accept / ignore it

thread.start()is not the same asthread.run()-thread.run()simply runs the runnable we pass to it inside the calling threadpublic static void main(String [] args) { Thread thread = new Thread(() -> System.out.println("Hello from " + Thread.currentThread().getName())); thread.setName("New Thread"); thread.run(); // Hello from main }- Thread.State - an enum, with the following states -

- NEW - created but not yet started

- RUNNABLE - thread is available for execution / already executing on some processor

- BLOCKED - blocked for a monitor / lock

- WAITING - a thread goes into this state after we call

object.wait()orsome_thread.join()- so, the idea is that the thread now waits for some other thread’s action?- a thread can also go “out” of this state after we call

object.notify()from elsewhere to wake this thread up

- a thread can also go “out” of this state after we call

- TIMED_WAITING - same as above but with timeouts? threads on calling

Thread.sleepalso go to this state - TERMINATED - after thread has finished execution

- when we override the

startmethod, we need to callsuper.start() - when we say

Thread.sleep(x), first the thread goes into timed_waiting state. after the time when it does go into runnable state, there is no guarantee that the thread will iimediately be scheduled on a core - a core might be occupied by some other thread - an

IIllegalMonitorStateExceptionis thrown if we try to callawait/signalon a Condition without locking thelockfirst

Example - Rate Limiting Using Token Bucket Filter

- a bucket gets filled at the rate of 1 token per second

- the bucket has a capacity of n

- there can be multiple consumers - when they ask for a thread, they should get a token - they will be stalled till a token is available

- producer code -

@SneakyThrows private void produce() { while (true) { synchronized (this) { if (tokens < capacity) { tokens += 1; } notifyAll(); } Thread.sleep(1000); } } void startProducing() { Thread producerThread = new Thread(this::produce); producerThread.setDaemon(true); producerThread.start(); } - consumer code -

@SneakyThrows void consume() { synchronized (this) { while (tokens == 0) { wait(); } tokens -= 1; } } - final total bucket code -

static class Bucket { int tokens; int capacity; public Bucket(int capacity) { this.capacity = capacity; tokens = 0; } private void produce() { ... } private void startProducing() { ... } private void consume() { ... } }

A Good Test

- notice how since we start after 7 seconds, the first 5 consumer threads get their token instantly

- while the remaining three threads take 1 second each

- output -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

1716809831> thread 0 consumed successfully 1716809831> thread 1 consumed successfully 1716809831> thread 2 consumed successfully 1716809831> thread 3 consumed successfully 1716809831> thread 5 consumed successfully 1716809832> thread 4 consumed successfully 1716809833> thread 7 consumed successfully 1716809834> thread 6 consumed successfully

Bucket bucket = new Bucket(5);

bucket.startProducing();

Thread.sleep(7);

List<Thread> threads = new ArrayList<>();

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i++) {

Thread t = new Thread(() -> {

bucket.consume();

System.out.printf("%s> %s consumed successfully\n",

System.currentTimeMillis() / 1000, Thread.currentThread().getName());

});

t.setName("thread " + i);

threads.add(t);

}

Thread.sleep(5000);

threads.forEach(Thread::start);

for (Thread t : threads) {

t.join();

}

Example - Implementing a Semaphore

- java does have a semaphore, but we initialize it with initial permits

- there is no limit as such to the maximum permits in java’s semaphore

- implement a semaphore which is initialized with maximum allowed permits, and is also initialized with the same number of permits

- acquire -

@SneakyThrows synchronized void acquire() { while (availablePermits == 0) { wait(); } Thread.sleep(1000); availablePermits -= 1; notify(); } - release -

@SneakyThrows synchronized void release() { while (availablePermits == maxPermits) { wait(); } Thread.sleep(1); availablePermits += 1; notify(); } - actual semaphore -

static class Semaphore { private final int maxPermits; private int availablePermits; public Semaphore(int maxPermits) { this.maxPermits = maxPermits; this.availablePermits = maxPermits; } synchronized void acquire() { ... } synchronized void release() { ... } } - tips for testing -

- initialize using 1

- make the thread calling acquire slow

- make the thread calling release fast

- show release would not be called until acquire is called

Example - Implementing a Read Write Lock

- acquiring read -

@SneakyThrows synchronized void acquireRead() { while (isWriteAcquired) { wait(); } readers += 1; } - acquiring write -

@SneakyThrows synchronized void acquireWrite() { while (isWriteAcquired || readers != 0) { wait(); } isWriteAcquired = true; } - releasing read - my thought - just call

notifyto wake up just 1 writersynchronized void releaseRead() { readers -= 1; notify(); } - releasing write - my thought - call

notifyAllto wake up all writerssynchronized void releaseWrite() { isWriteAcquired = false; notifyAll(); }

Example - Dining Philosophers

- five philosophers - either eat or think

- they share five forks between them

- they need two forks to eat - so at a time, only two philosophers can eat

- remember - we can easily end up in a deadlock - assume all philosophers acquire the fork on their left, and now all of them will wait for the fork on their right. two solutions are

- only four philosophers at a time try acquiring a fork. this way, at least one philosopher will always be able to acquire two forks and it solves the problem

- all the philosophers but one try acquiring the left fork first, and then the right fork. one of them tries acquiring the right fork first. note that the order in which forks are released does not matter

- only allow picking up of the fork if both the forks are available, do not pick and hold one fork

- tip - do not insert sleeps - we will see a deadlock quickly

Table

static class Table {

private final Semaphore[] forks;

Table(int size) {

forks = new Semaphore[size];

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

forks[i] = new Semaphore(1);

}

}

@SneakyThrows

private void acquire(int philosopherId) {

forks[philosopherId].acquire();

forks[(philosopherId + 1) % forks.length].acquire();

}

private void release(int philosopherId) {

forks[philosopherId].release();

forks[(philosopherId + 1) % forks.length].release();

}

}

Philosopher

static class Philosopher {

private final Table table;

private final Integer id;

public Philosopher(Table table, Integer id) {

this.table = table;

this.id = id;

}

void start() {

while (true) {

contemplate();

eat();

}

}

@SneakyThrows

private void contemplate() {

System.out.printf("%d thinking...\n", id);

}

@SneakyThrows

private void eat() {

table.acquire(id);

System.out.printf("%d eating...\n", id);

table.release(id);

}

}

Main Method

int size = 5;

Table table = new Table(size);

List<Thread> threads = new ArrayList<>();

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

Philosopher philosopher = new Philosopher(table, i);

Thread thread = new Thread(philosopher::start);

threads.add(thread);

}

for (Thread thread : threads) {

thread.start();

}

for (Thread thread : threads) {

thread.join();

}

Solution 1

// inside constructor

eatingPhilosophers = new Semaphore(size - 1);

@SneakyThrows

private void acquire(int philosopherId) {

eatingPhilosophers.acquire();

forks[philosopherId].acquire();

forks[(philosopherId + 1) % forks.length].acquire();

eatingPhilosophers.release();

}

Solution 2

@SneakyThrows

private void acquire(int philosopherId) {

if (philosopherId == 0) {

forks[(philosopherId + 1) % forks.length].acquire();

forks[philosopherId].acquire();

} else {

forks[philosopherId].acquire();

forks[(philosopherId + 1) % forks.length].acquire();

}

}