- till now, whenever we called plot on pandas series, it was actually calling matplotlib bts

- however, it can have limitations, which is when we might want to interact with matplotlib

- most common way of importing matplotlib -

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

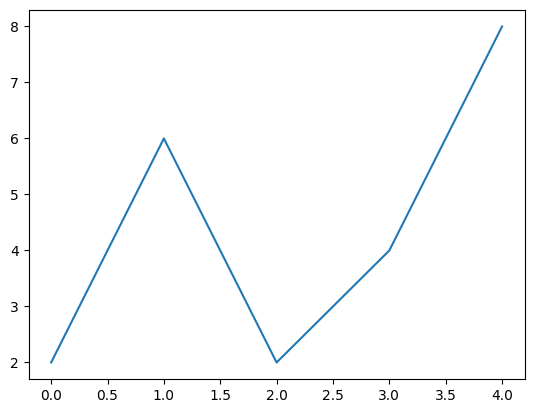

- when we do the following, it defaults values on the x axes to be 0, 1, 2, …

plt.plot([2, 6, 2, 4, 8])

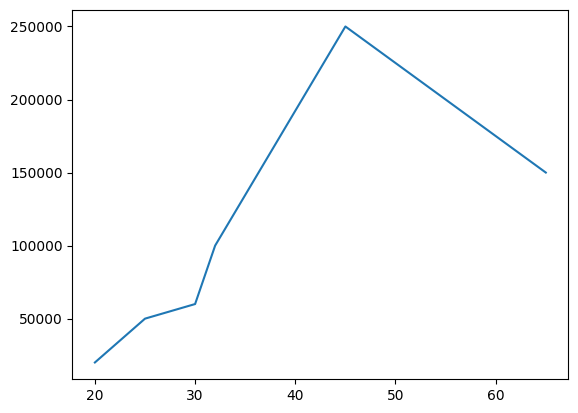

- we can specify values for both x and y as follows -

salaries = [20000, 50000, 60000, 100000, 250000, 150000]

ages = [20, 25, 30, 32, 45, 65]

plt.plot(ages, salaries)

- note - when we call plot in jupyter notebook, before the actual graph, we see a line like this -

[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x7cd66c249180>]. this is actually the output of plot, but jupyter is smart enough to show us the output at the back of it as well. we will have to call plt.show() if we are not working on a jupyter notebook - matplotlib terminology - the top level container is a figure

- a figure can have multiple axes

- each axes is a combination of labels, data, etc

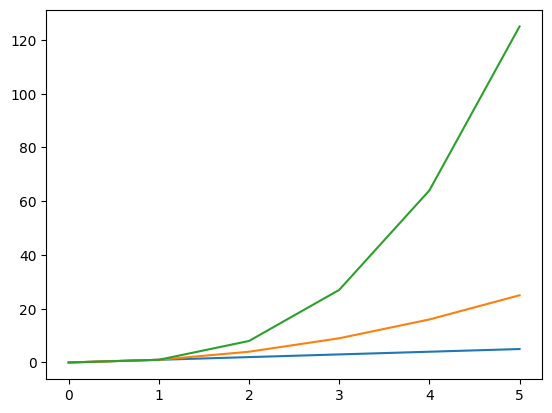

- assume we have the following sample data -

nums = range(6)

nums_squared = [num**2 for num in nums]

nums_cubed = [num**3 for num in nums]

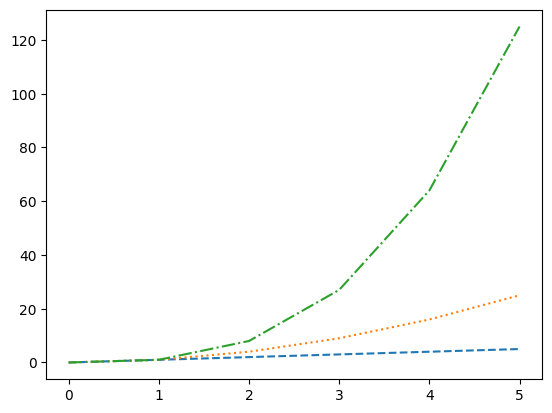

- when we have the following code, all of them are plotted on the same figure and the same axes

plt.plot(nums)

plt.plot(nums_squared)

plt.plot(nums_cubed)

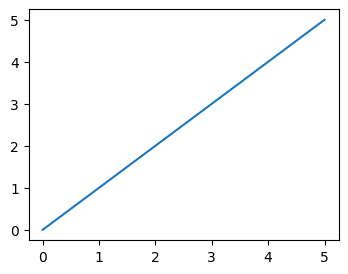

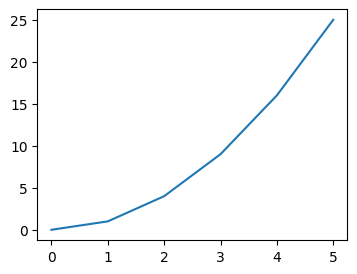

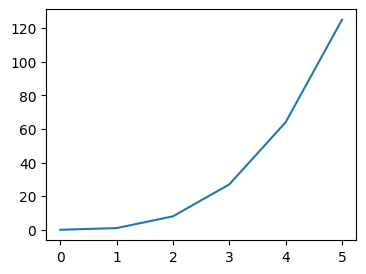

- we call figure to create a new figure and make it the current figure. so when we call plot, it basically plots on the current active figure. so, with the code below, all of them are plotted on different figures

plt.figure(figsize=(4,3))

plt.plot(nums)

plt.figure(figsize=(4,3))

plt.plot(nums_squared)

plt.figure(figsize=(4,3))

plt.plot(nums_cubed)

- note how we control the size of a figure in matplotlib - we can pass figsize and dpi or dots per inch to figure. i usually just touch figsize, which defaults to 6.4, 4.8

- we can specify the linestyle when plotting as follows. notice the shorthand at the third call as well

plt.plot(nums, nums, linestyle='dashed')

plt.plot(nums, nums_squared, linestyle='dotted')

plt.plot(nums, nums_cubed, linestyle='-.')

- when calling plot, we can specify parameters like color, linewidth, etc as well if needed

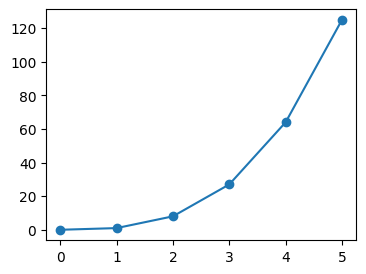

- we can also specify markers and their styling

plt.plot(nums, nums_cubed, marker='o')

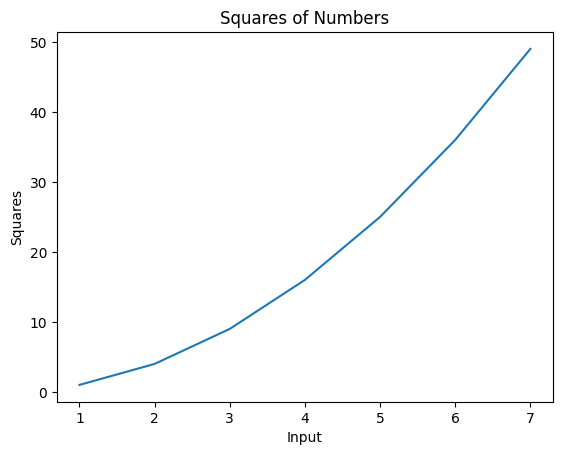

- we can use title to set a title for the axes, and labels to set labels for the x and y axis individually

plt.plot(nums, nums_squared)

plt.title("Squares of Numbers")

plt.xlabel("Input")

plt.ylabel("Squares")

- remember - all these methods we see - plot, title, xlabel and ylabel, and others that we see later - also accept a ton of options to control the size, spacing, color, positioning, etc. refer documentation as and when needed

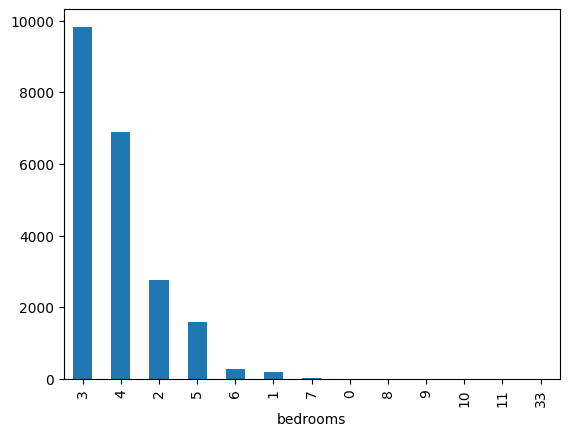

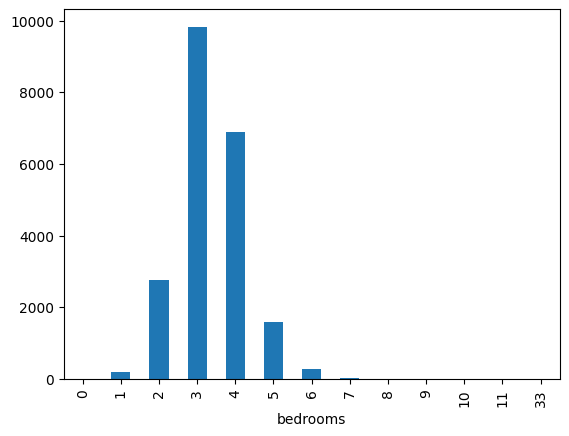

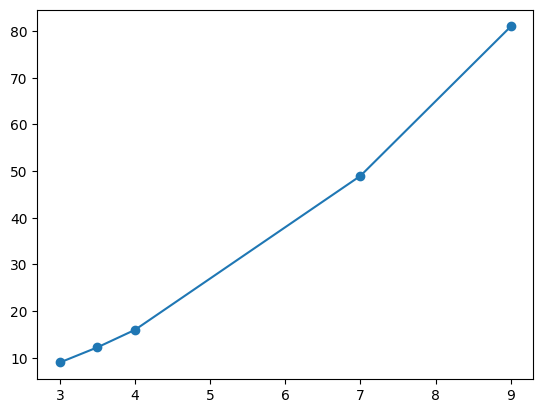

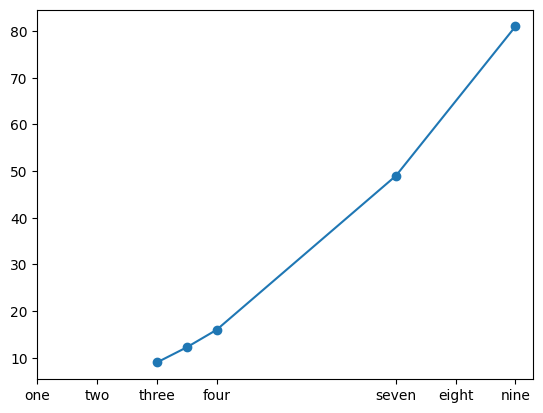

- when we try to plot the below, look at the default graph. notice how on x axis for e.g., matplotlib itself decided that it should start the ticks from 3 etc

nums = [3, 3.5, 4, 7, 9]

nums_squared = [num**2 for num in nums]

plt.plot(nums, nums_squared, marker='o')

- option 1 - we can add custom ticks using xticks and yticks. it serves two purposes -

- we can only provide the first argument. this controls what ticks should show up

- we can provide the second argument as well. this controls what the actual tick should be named inside the graph

plt.plot(nums, nums_squared, marker='o')

plt.xticks([1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9], ['one', 'two', 'three', 'four', 'seven', 'eight', 'nine'])

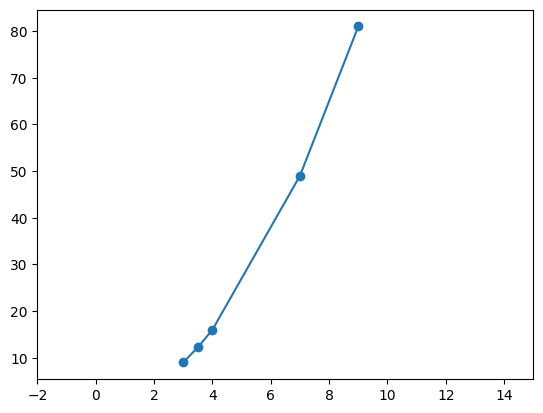

- option 2 - we can only modify the limits. e.g. we would like the x axis start from -2 and end at 20 for some reason

plt.plot(nums, nums_squared, marker='o')

plt.xlim(-2, 15)

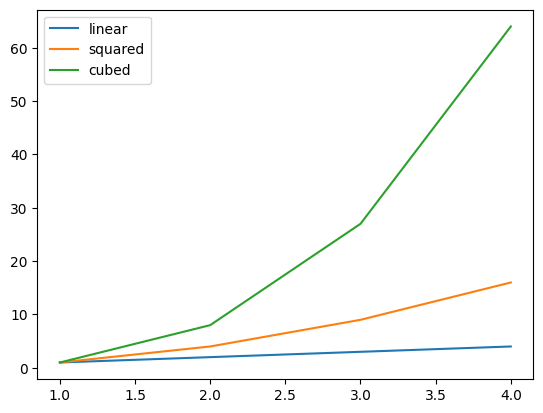

- legend - helps distinguish between the different graphs using labels when they are on the same axes in the same figure

nums = [1, 2, 3, 4]

nums_squared = [num ** 2 for num in nums]

nums_cubed = [num ** 3 for num in nums]

plt.plot(nums, nums, label='linear')

plt.plot(nums, nums_squared, label='squared')

plt.plot(nums, nums_cubed, label='cubed')

plt.legend()

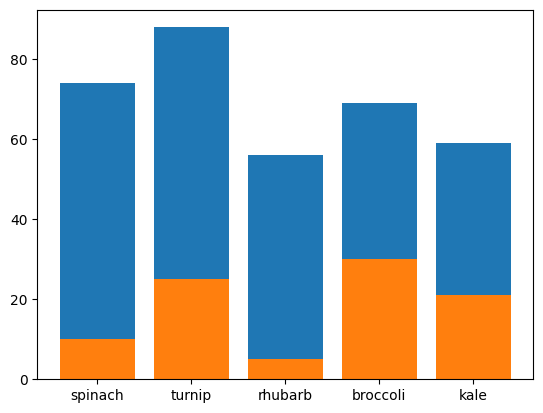

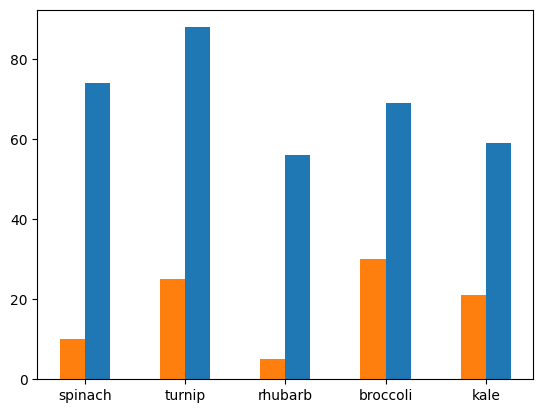

- plotting bar charts. assume we have the following data -

plants = ['spinach', 'turnip', 'rhubarb', 'broccoli', 'kale']

died = [10, 25, 5, 30, 21]

germinated = [74, 88, 56, 69, 59]

- by default, the different charts would be one on top of another -

plt.bar(plants, germinated)

plt.bar(plants, died)

- this is how i got them to show one beside another -

- i ensured width of the first graph is positive while the second one is negative, so that they appear on either sides of the x tick

- i also ensured they are 0.25% of their actual width, as this ensures the right spacing. if for e.g. i did 0.5, the second bar of a tick will touch the first bar of the next tick

- i set align to edge. this alsigns them to the edge of the tick. the default is center (refer the graph created by default above)

plt.bar(plants, germinated, width=0.25, align='edge')

plt.bar(plants, died, width=-0.25, align='edge')

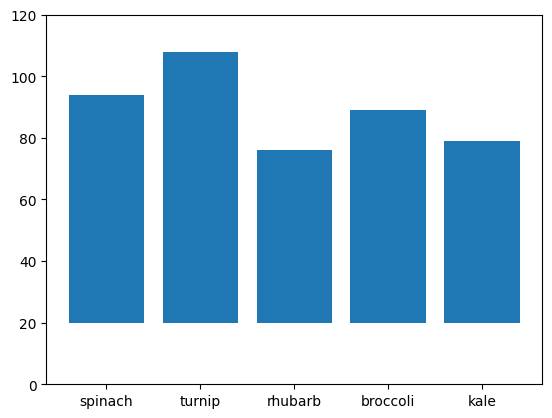

- bar also receives another keyword argument - bottom

plt.bar(plants, germinated, bottom=[20, 20, 20, 20, 20])

plt.ylim(0, 120)

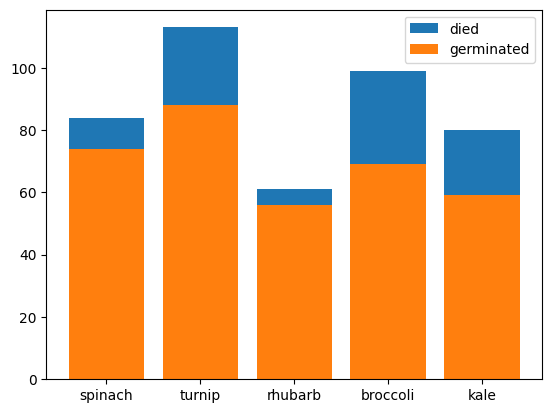

- use case of the stupidity above 🤣 - we can get the different bars to stack one on top of another. the y coordinates of one graph becomes the bottom of another

plt.bar(plants, died, bottom=germinated, label='died')

plt.bar(plants, germinated, label='germinated')

plt.legend()

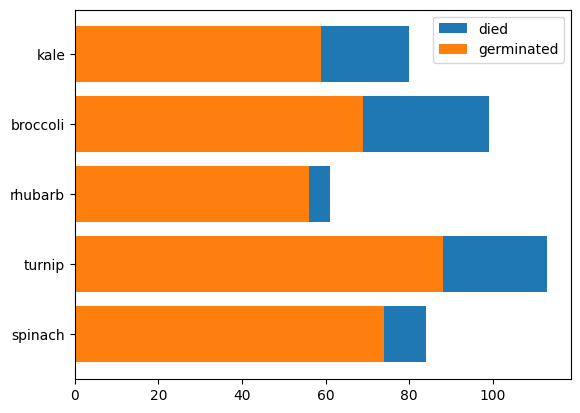

- we can use barh instead of bar for horizontal bar graphs. notice how for stacking, the bottom changes to left

plt.barh(plants, died, left=germinated, label='died')

plt.barh(plants, germinated, label='germinated')

plt.legend()

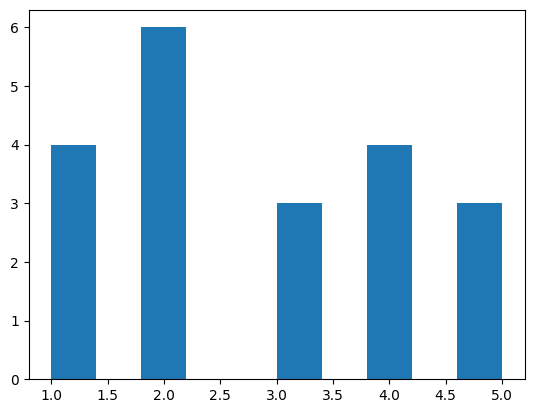

- histogram - assume we have the following data. note - i did a value count to explain the distribution of data -

nums = [1,2,2,3,5,4,2,2,1,1,3,4,4,2,1,5,2,3,4,5]

{ num: nums.count(num) for num in nums }

# {1: 4, 2: 6, 3: 3, 4: 4, 5: 3}

- when i try to create a histogram on this data, it looks as follows by default -

plt.hist(nums)

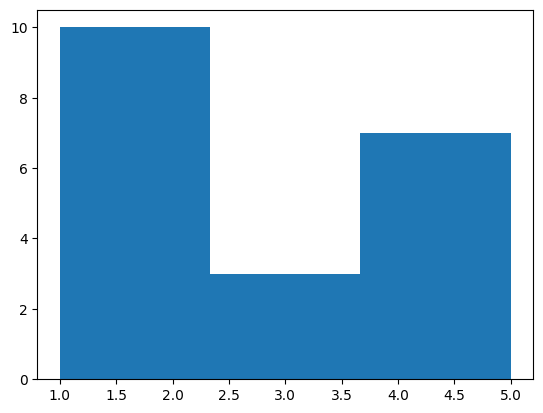

- we can configure the bins as follows. my understanding - 1 and 2 together have frequency of 10, 3 has frequency of 3 while 4 and 5 together have frequency of 7. now, the range has been divided into three parts 1-2.33, 2.33-3.66, 3.66-4.99, and the histogram has been plotted accordingly

plt.hist(nums, bins=3)

- histograms are a little different i feel because unlike pie chart, bar graph, etc where we give the actual values to be plotted, here, we only give a series of values and it autmatically calculates the frequency and bins them accordingly

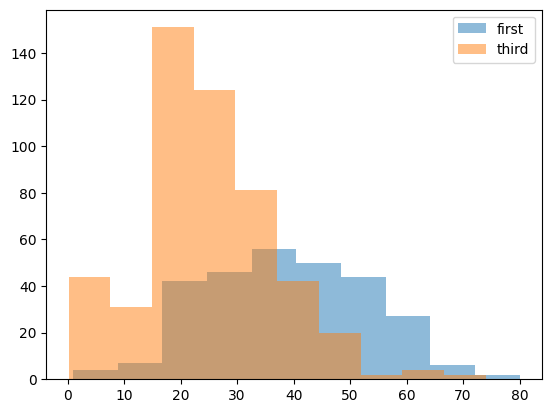

- a realisitic example - comparing the distribution of ages of people travelling in first class vs third class in the titanic. observation - more younger people were travelling in third class, wheras more older people were travelling in first class. also, note how we change the alpha to visualize them simultaneously

titanic = pd.read_csv('/content/drive/MyDrive/Python - Basic Data Analysis/titanic.csv')

# clean the age column

titanic.replace({ 'age': { '?': None } }, inplace=True)

titanic['age'] = titanic['age'].astype('float')

# extract the ages of first and third class

first_class_ages = titanic[titanic['pclass'] == 1]['age']

third_class_ages = titanic[titanic['pclass'] == 3]['age']

# plot the ages

plt.hist(first_class_ages, alpha=0.5, label='first')

plt.hist(third_class_ages, alpha=0.5, label='third')

plt.legend()

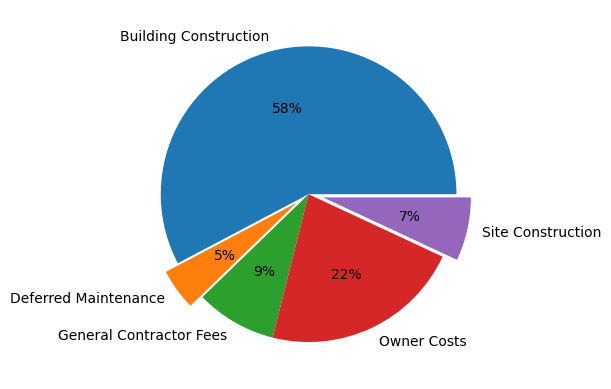

- pie charts

- we use the explode parameter to disconnect the sectors from the pie chart. the fraction determines how far out the sectors would be from the pie. the order is the same as the order of the labels

- we use the autopct parameter to add percentages inside the sectors. we are using

autopct='%.0f%%' here, if we would have used for e.g. autopct='%.2f', it would have shown in this form - 57.73 (with 2 decimal places and without the %)

plt.pie(costs, labels=labels, autopct='%0.0f%%', explode=(0, 0.1, 0, 0, 0.1))

plt.show()

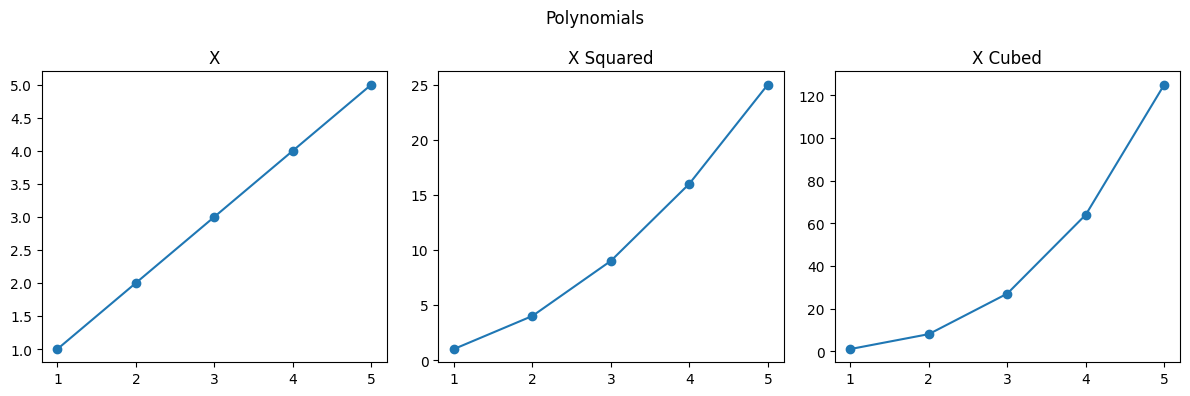

- subplots - multiple axes in the same figure

- we use subplot to tell the dimensions and the correct subplot index. in the example below, we say 1 row, 3 columns, and go 1, 2 and 3 respectively for the index

- title is used for individual axes headings while suptitle is used for the figure heading

- we call tight layout, as it helps python adjust the padding around subplots

nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

nums_squared = [num ** 2 for num in nums]

nums_cubed = [num ** 3 for num in nums]

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 4))

plt.suptitle("Polynomials")

plt.subplot(1, 3, 1)

plt.title("X")

plt.plot(nums, nums)

plt.subplot(1, 3, 2)

plt.title("X Squared")

plt.plot(nums, nums_squared)

plt.subplot(1, 3, 3)

plt.title("X Cubed")

plt.plot(nums, nums_cubed)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

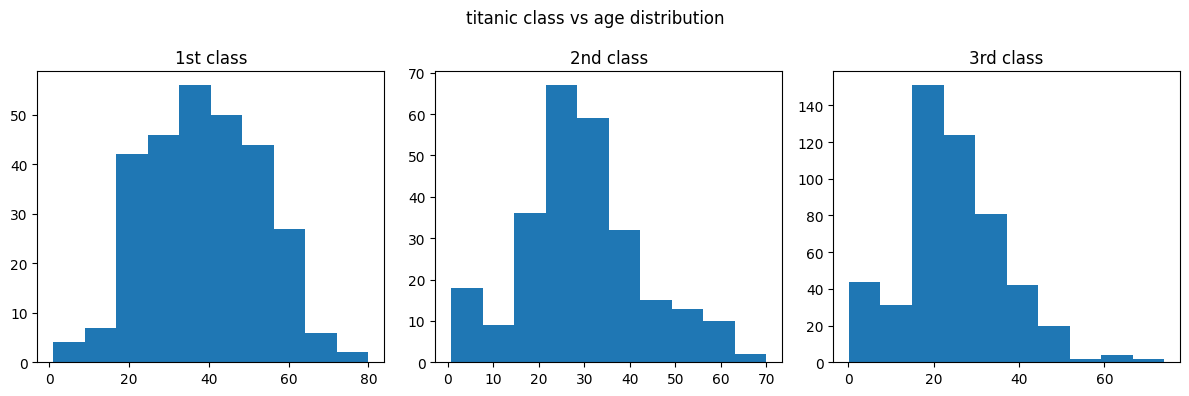

- now, imagine if we go back to our titanic example, and we want to plot all three classes - first second and third in different subplots -

titanic = pd.read_csv('/content/drive/MyDrive/Python - Basic Data Analysis/titanic.csv')

titanic['age'] = pd.to_numeric(titanic['age'], errors='coerce')

first_class_ages = titanic[titanic['pclass'] == 1]['age']

second_class_ages = titanic[titanic['pclass'] == 2]['age']

third_class_ages = titanic[titanic['pclass'] == 3]['age']

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 4))

plt.suptitle('titanic class vs age distribution')

plt.subplot(1, 3, 1)

plt.title('1st class')

plt.hist(first_class_ages)

plt.subplot(1, 3, 2)

plt.title('2nd class')

plt.hist(second_class_ages)

plt.subplot(1, 3, 3)

plt.title('3rd class')

plt.hist(third_class_ages)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

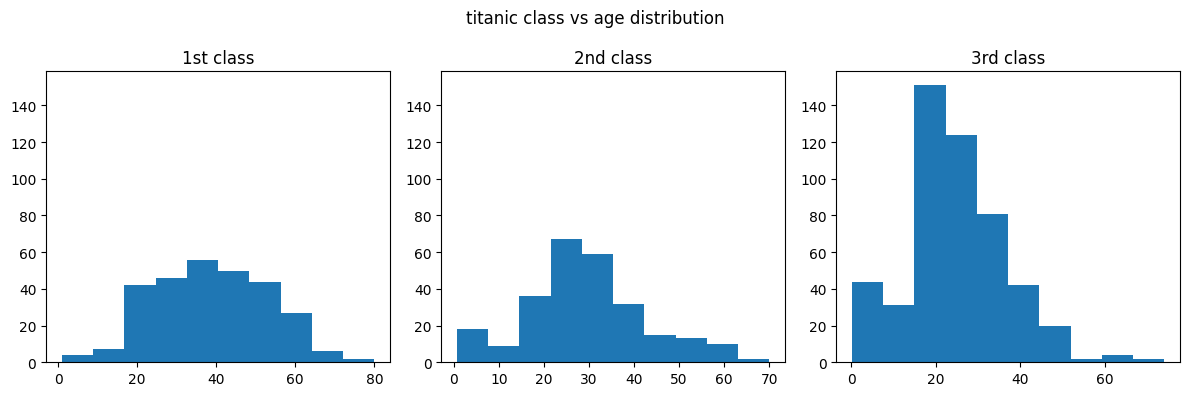

- issue - we know that the scale in the third vs other plots are different i.e. a lot more people are travelling in the third class than in the 2nd and 1st class. this is not evident right off the bat by looking at the graph. hence, we can specify the sharey parameter

# ...

axes = plt.subplot(1, 3, 1)

# ...

plt.subplot(1, 3, 2, sharey=axes)

# ...

plt.subplot(1, 3, 3, sharey=axes)

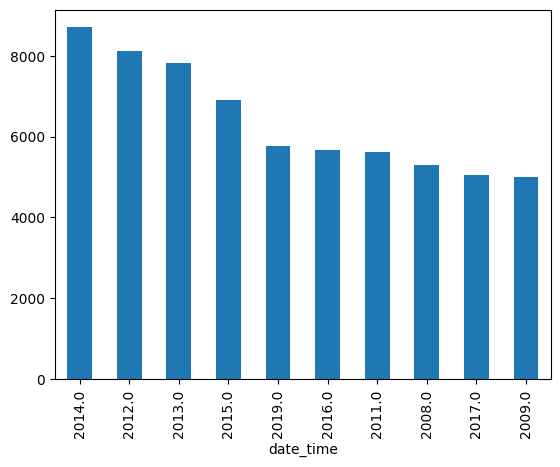

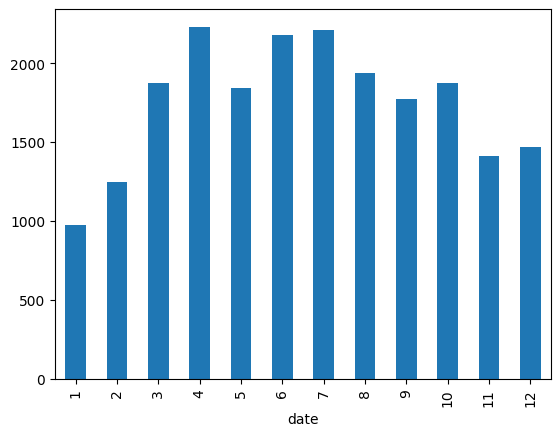

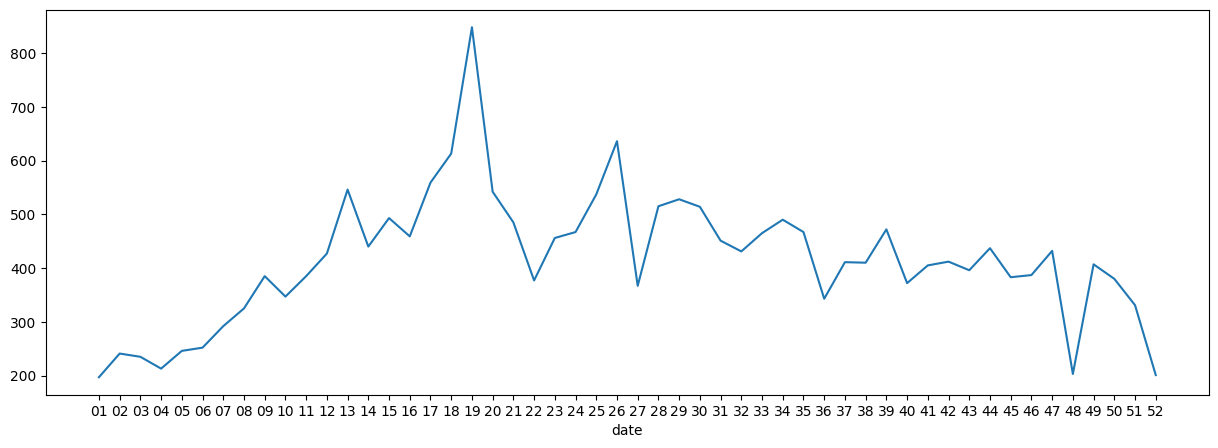

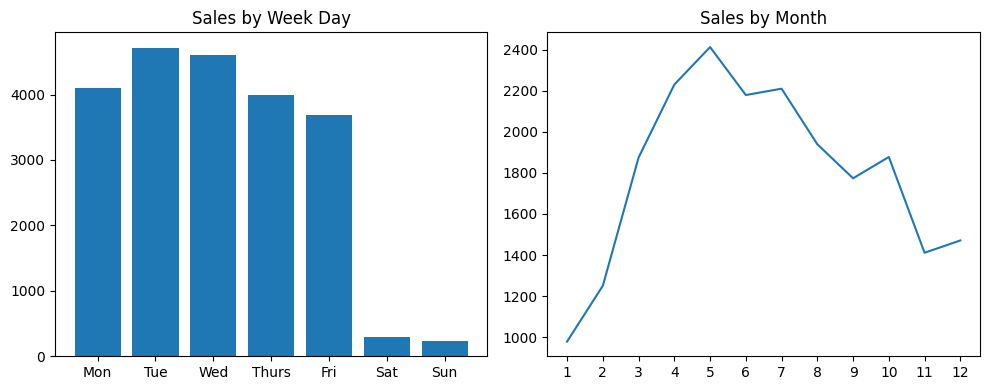

- question - write the code for achieving the below. note - do not use the plot method of pandas series and dataframes

houses = pd.read_csv('/content/drive/MyDrive/Python - Basic Data Analysis/kc_house_data.csv', parse_dates=['date'])

sales_by_month = houses['date'].dt.month.value_counts().sort_index()

# date

# 1 978

# 2 1250

# 3 1875

# 4 2231

# 5 2414

# 6 2180

# 7 2211

# 8 1940

# 9 1774

# 10 1878

# 11 1411

# 12 1471

sales_by_week_day = houses['date'].dt.day_of_week.value_counts().sort_index()

# date

# 0 4099

# 1 4715

# 2 4603

# 3 3994

# 4 3685

# 5 287

# 6 230

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 4))

plt.subplot(1, 2, 1)

week_days = ['Mon', 'Tue', 'Wed', 'Thurs', 'Fri', 'Sat', 'Sun']

plt.title('Sales by Week Day')

plt.xticks(sales_by_week_day.index, week_days)

plt.bar(sales_by_week_day.index, sales_by_week_day.values)

plt.subplot(1, 2, 2)

plt.xticks(range(1, 13))

plt.title('Sales by Month')

plt.plot(sales_by_month.index, sales_by_month.values)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

- note how we use index and values that we disccussed here

- we also had to sort by index first before beginning to plot, because value counts sorts by values by default

- notice the use of xticks for renaming the labels for weekdays. i had to do the same thing for months as well, otherwise the default was 2, 4, 6, 8…

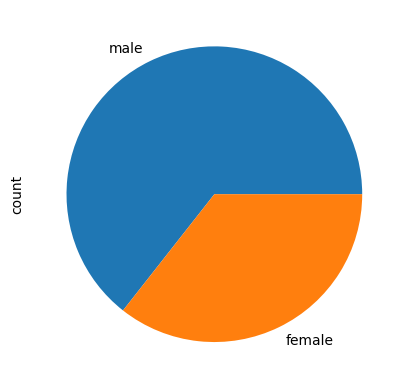

- plotting a pandas series

titanic['sex'].value_counts().plot(kind='pie')

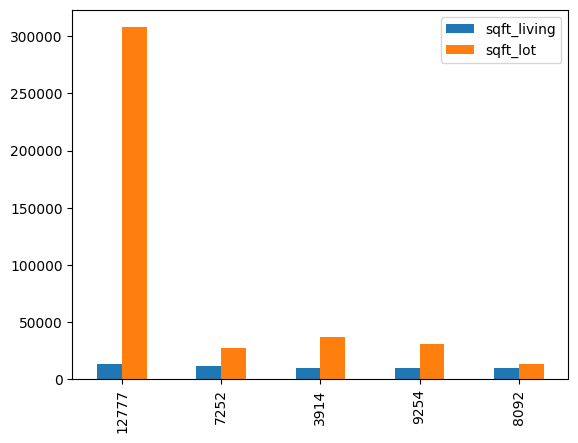

- plotting a pandas dataframe - note how it is making a bar for all columns automatically

house_area

# sqft_living sqft_lot

# 12777 13540 307752

# 7252 12050 27600

# 3914 10040 37325

# 9254 9890 31374

# 8092 9640 13068

house_area.plot(kind='bar')

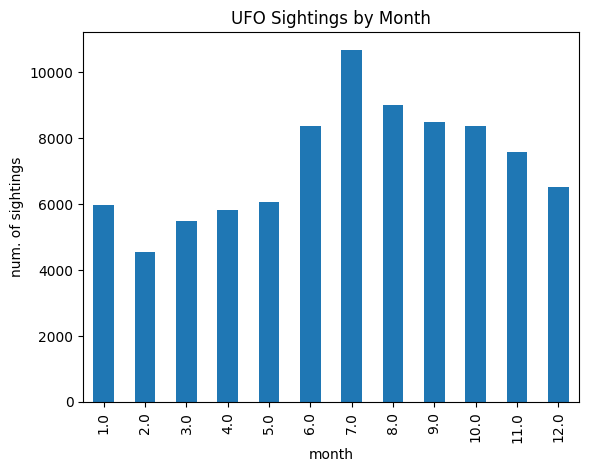

- ufo sightings by month - we use this series in the next few points, and this is what our data looks like -

ufo_sightings_by_month

# 1.0 5979

# 2.0 4559

# 3.0 5494

# 4.0 5817

# 5.0 6063

# 6.0 8357

# 7.0 10682

# 8.0 8997

# 9.0 8498

# 10.0 8371

# 11.0 7596

# 12.0 6525

- for providing parameters like title, we have two options -

- option 1 - in the same line. disadvantage - lesser options to configure styling etc

ufo_sightings_by_month.plot(kind='bar', title='UFO Sightings by Month', xlabel='month', ylabel='num. of sightings')

- option 2 - i think the central idea is instead of interacting only with pandas plot api, we mix with calls to matplotlib apis directly like we saw in matplotlib. advantage - now, we can configure styling etc

ufo_sightings_by_month.plot(kind='bar')

plt.title('UFO Sightings by Month')

plt.xlabel('month')

plt.ylabel('num. of sightings')

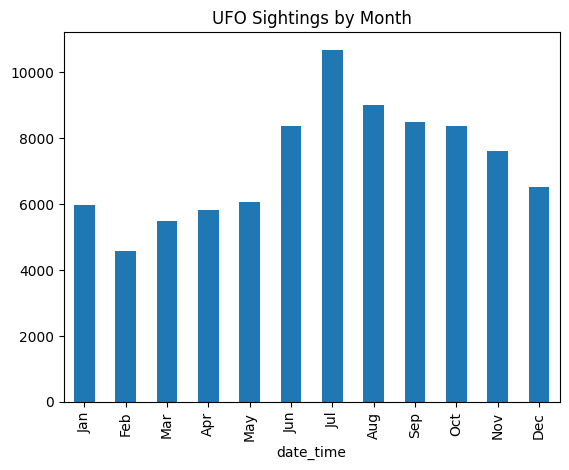

- now, we would like to use months abbreviations instead. we have multiple options -

- option 1 - use rename to rename indices

months_lookup = { idx + 1: months[idx] for idx in range(12) }

# {1: 'Jan', 2: 'Feb', 3: 'Mar', 4: 'Apr', 5: 'May', 6: 'Jun', 7: 'Jul', 8: 'Aug', 9: 'Sep', 10: 'Oct', 11: 'Nov', 12: 'Dec'}

ufo_sightings_by_month_abbrev = ufo_sightings_by_month.rename(index=months_lookup)

ufo_sightings_by_month_abbrev.plot(kind='bar', title='UFO Sightings by Month')

- option 2 - use xticks. this is useful if we just want to modify plots but it might make testing etc difficult

ufo_sightings_by_month.plot(kind='bar', title='UFO Sightings by Month')

plt.xticks(range(12), labels=months)

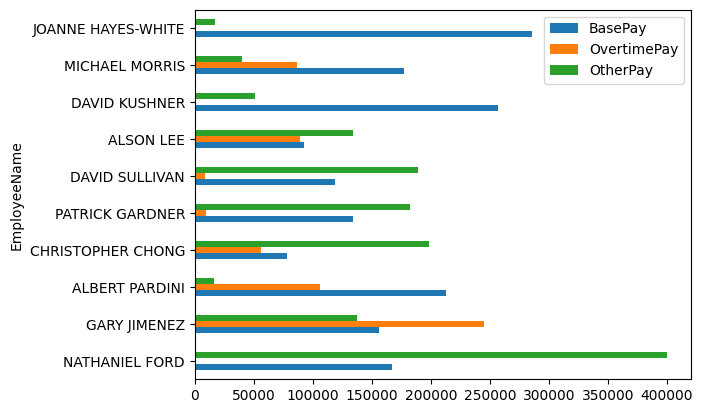

- by default, bar charts for dataframes looks as follows. understand that pandas is coming with reasonable defaults and helpers. there was so much effort was required from our end when doing this manually using matplotlib - specifying labels and legends, specifying the align property with a negative width, etc

salaries

# BasePay OvertimePay OtherPay

# EmployeeName

# NATHANIEL FORD 167411.18 0.00 400184.25

# GARY JIMENEZ 155966.02 245131.88 137811.38

# ALBERT PARDINI 212739.13 106088.18 16452.60

# CHRISTOPHER CHONG 77916.00 56120.71 198306.90

salaries.plot(kind='barh')

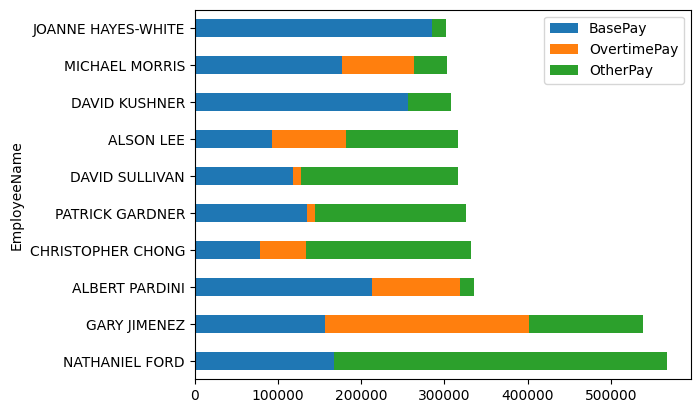

- making a stacked version too is so much easier compared to doing it via matplotlib manually by specifying bottom / left etc

salaries.plot(kind='barh', stacked=True)

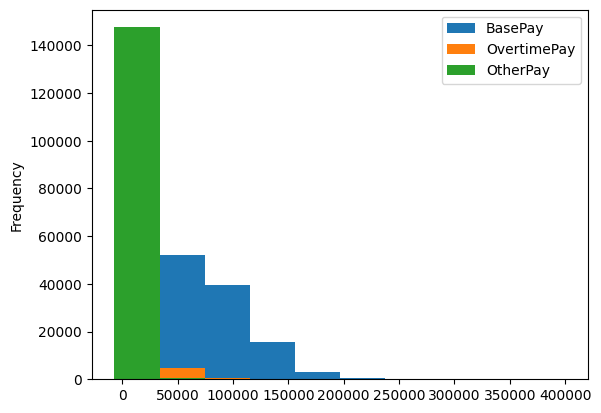

- the usual way -

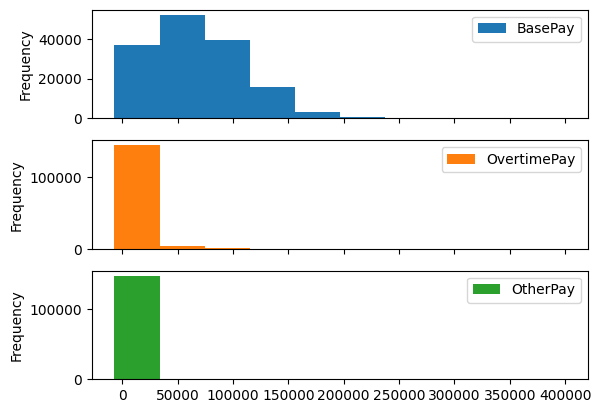

.plot(kind='hist'). it creates all graphs in the same axessalaries.plot(kind='hist')

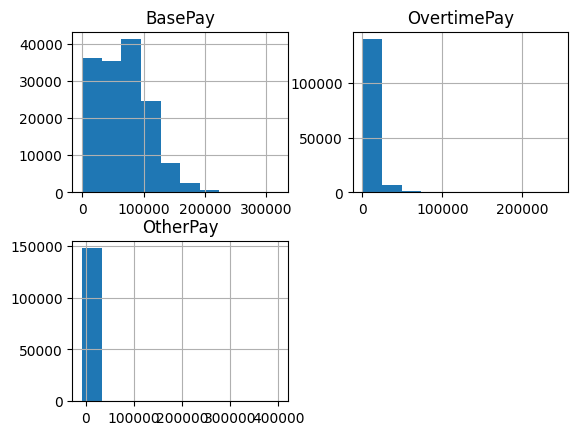

- calling

.hist() directly. it creates different axes for the different columns - feels like subplotssalaries.hist()

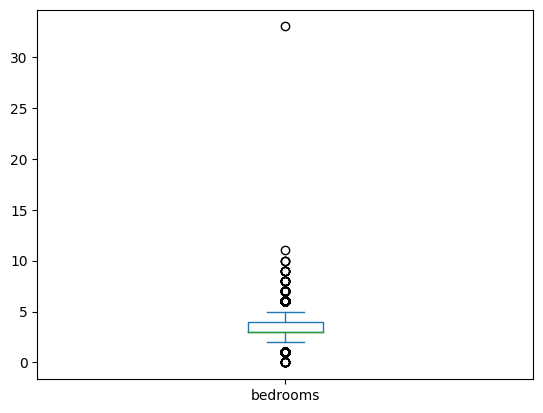

- box plot - this too helps visualize distribution of values like histogram. summary according to me, might be wrong -

- we have a line at the median (the green line)

- the general distribution of data lies between the two whiskers (the two standalone blue lines)

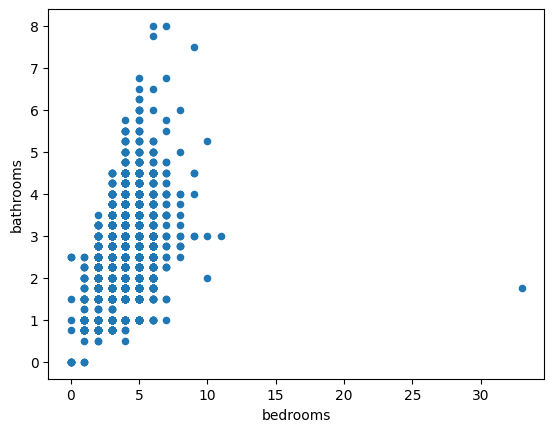

- the fliers depict the outliers (the circles). e.g. one house had 33 or so bedrooms, so look at the boxplot

houses['bedrooms'].plot(kind='box')

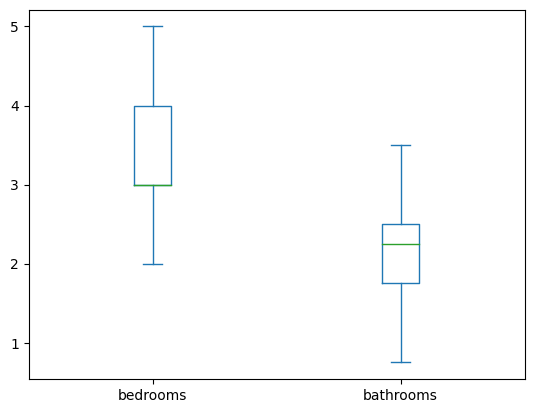

- we can view the list of configuration parameters here. e.g. we can disable the fliers

houses[['bedrooms', 'bathrooms']].plot(kind='box', showfliers=False)

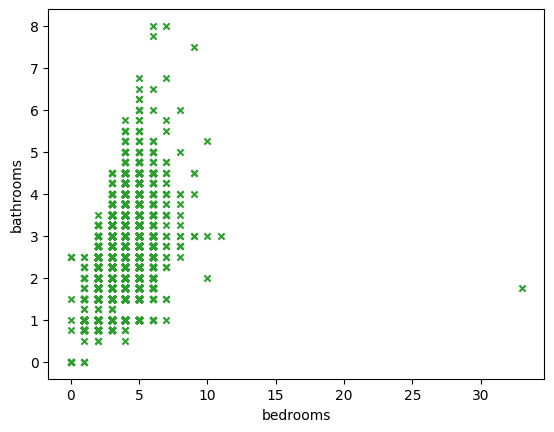

- scatter plot - how different variables, e.g. bedrooms and bathrooms correlate to eachother. refer this for different configuration options

houses.plot(kind='scatter', x='bedrooms', y='bathrooms', marker='x', c='#2ca02c')

- adding multiple graphs to the same axes on the same figure - same as we saw in matplotlib i.e. we need to call figure on plt for creating a new figure, else the current active figure is used

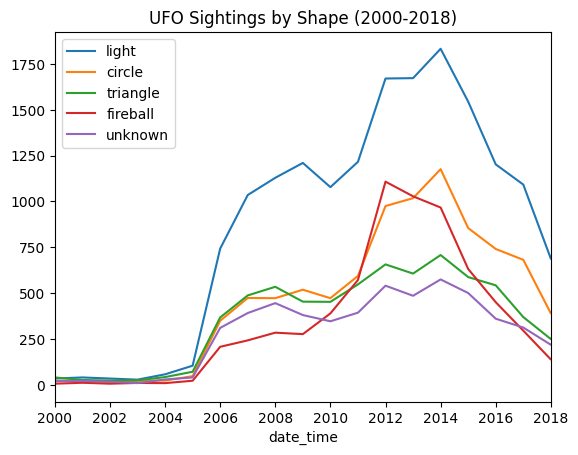

- e.g. - ufo sightings have a shape attribute. find the 5 most common shapes, and plot them on the same axes. use a legend to differentiate between them. plot them for the range 2000-2018

common_shapes = ufos['shape'].value_counts().nlargest(5)

for common_shape in common_shapes.index:

years = ufos[ufos['shape'] == common_shape]['date_time'].dt.year

years.value_counts().sort_index().plot(kind='line', label=common_shape)

plt.legend()

plt.xlim(2000, 2018)

plt.title('UFO Sightings by Shape (2000-2018)')

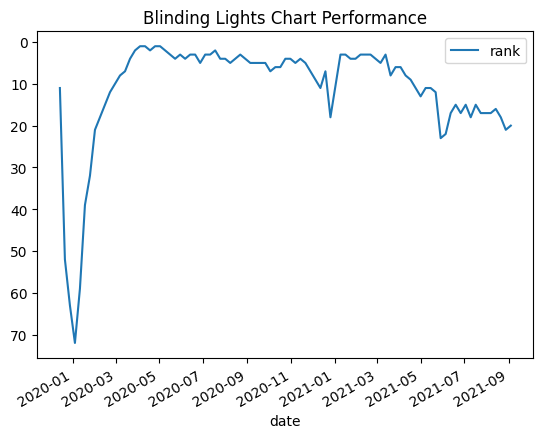

- e.g. plot how blinding lights performed on the charts. note how we can specify the x and y attributes when plotting dataframes. also, note how we can invert the y axis - a rank is better when lower, and we want to show a higher rank using a peak / lower rank using a trench

billboard_charts = pd.read_csv('/content/drive/MyDrive/Python - Basic Data Analysis/billboard_charts.csv', parse_dates=['date'])

blinding_lights = billboard_charts[billboard_charts['song'] == 'Blinding Lights']

blinding_lights.plot(y='rank', x='date')

plt.gca().invert_yaxis()

plt.title('Blinding Lights Chart Performance')

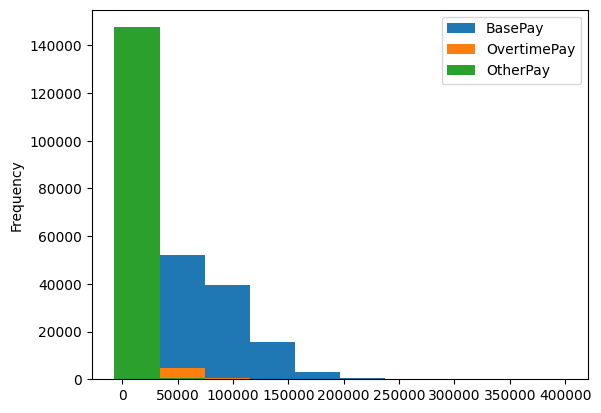

- when we try plotting a dataframe, the different columns would be plotted on the same axes by default

salaries.plot(kind='hist')

- we can create subplots instead just by passing in keyword arguments

salaries.plot(kind='hist', subplots=True)

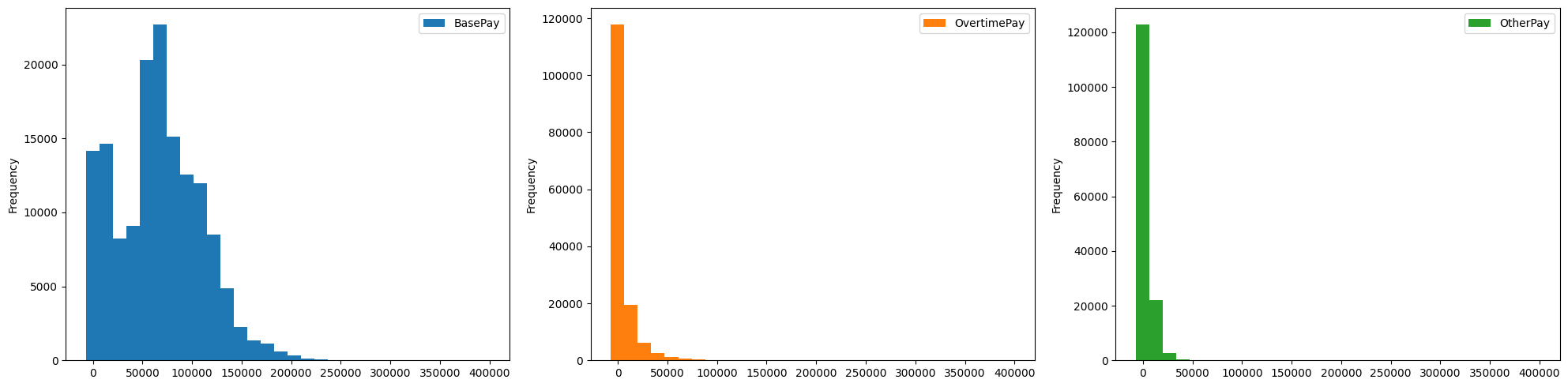

- we can configure other parameters like layout (the dimensions), sharex / sharey, etc as well, already discussed in matplotlib

salaries.plot(kind='hist', subplots=True, layout=(1, 3), figsize=(20, 5), sharex=True, bins=30)

plt.tight_layout()

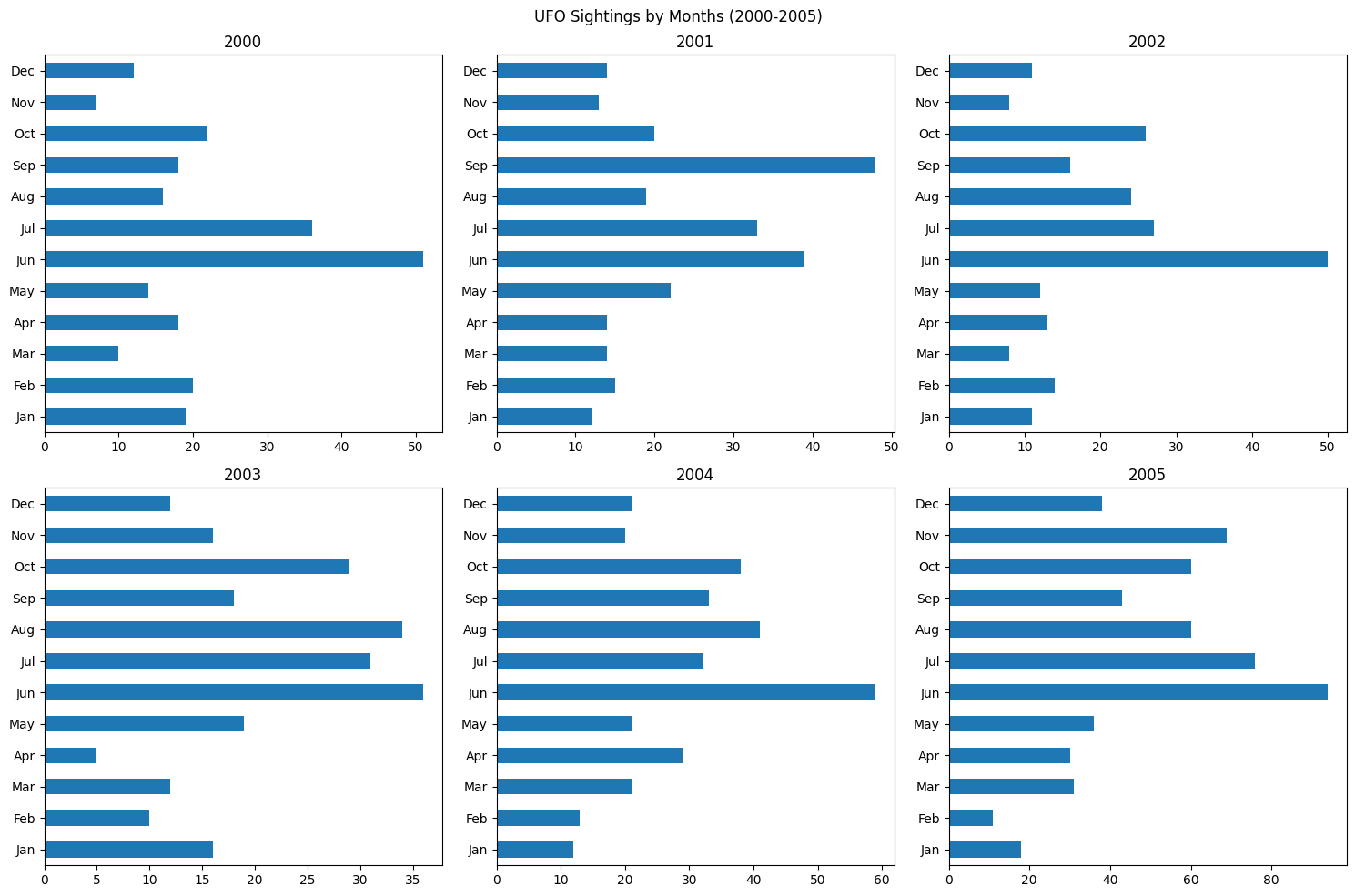

- note, my understanding - the above method of passing in true for the subplots keyword argument works because we wanted to plot the different columns of the same dataframe. what if we wanted to plot entirely different series etc on the same figure on different axes. we use a combination of interacting with matplotlib apis directly and through pandas apis. apis used -

- subplots can be called for setting the dimensions of the subplot, setting figure size, etc. it returns both the figure and the axes created in the process. the axes we receive has the same rows / columns as the dimensions we specify. note that parameters like

sharex / sharey can be passed into this subplots call as well - note how we pass in axes argument to plot of pandas series / dataframe

months = ['Jan', 'Feb', 'Mar', 'Apr', 'May', 'Jun', 'Jul', 'Aug', 'Sep', 'Oct', 'Nov', 'Dec']

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 3, figsize=(15, 10))

data_2000 = ufos[ufos['date_time'].dt.year == 2000]['date_time'].dt.month.value_counts().sort_index()

data_2000.plot(kind='barh', ax=axes[0][0], ylabel='', title=2000)

axes[0][0].set_yticks(range(12), labels=months)

data_2001 = ufos[ufos['date_time'].dt.year == 2001]['date_time'].dt.month.value_counts().sort_index()

data_2001.plot(kind='barh', ax=axes[0][1], ylabel='', title=2001)

axes[0][1].set_yticks(range(12), labels=months)

data_2002 = ufos[ufos['date_time'].dt.year == 2002]['date_time'].dt.month.value_counts().sort_index()

data_2002.plot(kind='barh', ax=axes[0][2], ylabel='', title=2002)

axes[0][2].set_yticks(range(12), labels=months)

data_2003 = ufos[ufos['date_time'].dt.year == 2003]['date_time'].dt.month.value_counts().sort_index()

data_2003.plot(kind='barh', ax=axes[1][0], ylabel='', title=2003)

axes[1][0].set_yticks(range(12), labels=months)

data_2004 = ufos[ufos['date_time'].dt.year == 2004]['date_time'].dt.month.value_counts().sort_index()

data_2004.plot(kind='barh', ax=axes[1][1], ylabel='', title=2004)

axes[1][1].set_yticks(range(12), labels=months)

data_2005 = ufos[ufos['date_time'].dt.year == 2005]['date_time'].dt.month.value_counts().sort_index()

data_2005.plot(kind='barh', ax=axes[1][2], ylabel='', title=2005)

axes[1][2].set_yticks(range(12), labels=months)

plt.suptitle(f'UFO Sightings by Months (2000-2005)')

plt.tight_layout()

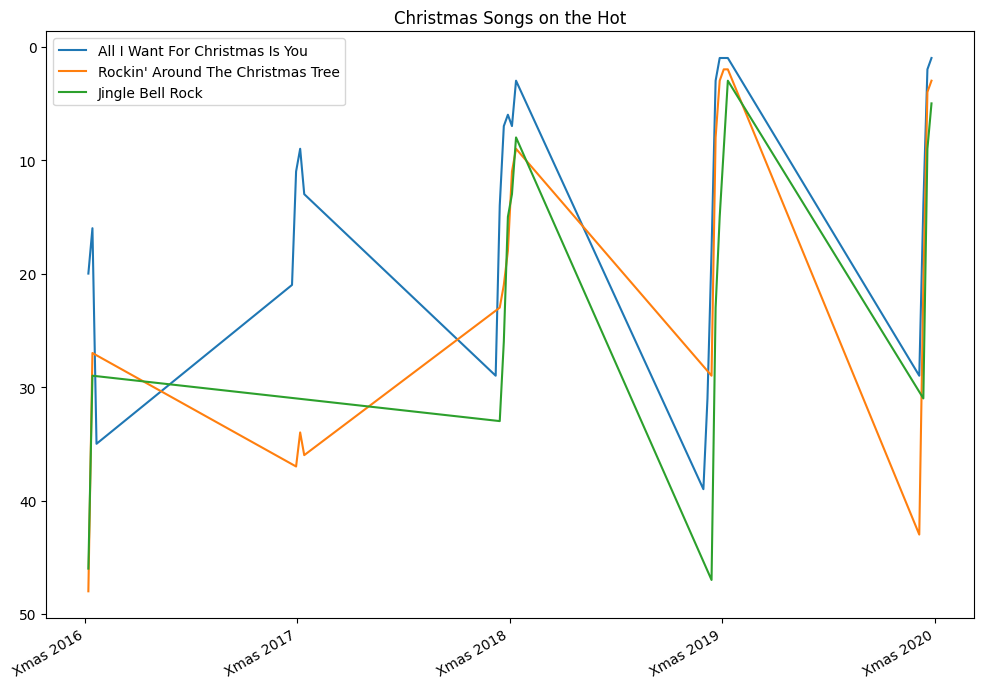

- for e.g. reproduce the graph below -

- this time around, there is just one axes. so, we can call set xticks, set title, etc on this one axes itelf

- again, since this is ranks of songs, we invert the y axis

- the labels on x axes was another challenge here, but easy when using xticks

- pandas, matplotlib, etc are smart enough to understand dates even if we specify them like strings - note how we specify strings for dates when using in between and setting xticks

years = [2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020]

christmases = [f'{year}-12-25' for year in years]

# ['2016-12-25', '2017-12-25', '2018-12-25', '2019-12-25', '2020-12-25']

songs = [

{ 'song': 'All I Want For Christmas Is You', 'artist': 'Mariah Carey' },

{ 'song': 'Rockin\' Around The Christmas Tree', 'artist': 'Brenda Lee' },

{ 'song': 'Jingle Bell Rock', 'artist': 'Bobby Helms' }

]

period = billboard_charts['date'].between(christmases[0], christmases[-1])

_, axes = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(10, 7))

plt.gca().invert_yaxis()

years = [2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020]

christmas_values = [pd.to_datetime(f'12-25-{year}') for year in years]

christmas_labels = [f'Xmas {year}' for year in years]

axes.set_xticks(christmas_values, christmas_labels)

axes.set_title('Christmas Songs on the Hot')

for song in songs:

condition = (billboard_charts['song'] == song['song']) & (billboard_charts['artist'] == song['artist'])

billboard_charts[condition & period].plot(kind='line', x='date', y='rank', ax=axes, label=song['song'], xlabel='')

plt.legend(loc='upper left')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

- for saving a figure to a local file, use

savefig(path.png)

- assume i have data for stocks of different cars like below -

car_stocks

# Symbol Date Open High Low Close Adj Close Volume

# 0 RIVN 2021-11-10 106.750000 119.459999 95.199997 100.730003 100.730003 103679500

# 1 RIVN 2021-11-11 114.625000 125.000000 108.010002 122.989998 122.989998 83668200

# 2 RIVN 2021-11-12 128.645004 135.199997 125.250000 129.949997 129.949997 50437500

- to get the mean of a particular stock, i can do the following -

car_stocks[car_stocks['Symbol'] == 'RIVN']['Close'].mean() # 127.523

- but what if i wanted the mean of all of the stocks individually in a dataframe? i can do it as follows

car_stocks.groupby('Symbol')['Close'].mean()

# Symbol

# GM 62.164615

# LCID 49.829231

# RIVN 127.523077

# Name: Close, dtype: float64

- notice how groupby gives us a pandas data frame group by object

car_stocks.groupby('Symbol')

# <pandas.core.groupby.generic.DataFrameGroupBy object at 0x77f885d61a90>

- we can call ngroups to see the number of groups -

car_stocks.groupby('Symbol').ngroups # 3

- we can call groups to see the actual groups. it is a dictionary, where the keys are the actual keys we used to group, while the values are the indices of the rows

car_stocks.groupby('Symbol').groups

# {'GM': [26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38],

# 'LCID': [13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25],

# 'RIVN': [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]}

- iterating over the dataframe group by object using a for each group - we get back a tuple of the form group name, dataframe. ofcourse, the dataframe only contains rows belonging to the group. the columns used in the group by clause would not be present in the dataframe. use case - useful when the aggregation functions available to us by default are not enough, and we want to run some custom functionality

for name, group in car_stocks.groupby('Symbol'):

print(name)

print('--------------------')

print(group[['Low', 'High']].describe())

print('\n')

# GM

# --------------------

# Low High

# mean 61.051539 63.129231

# min 57.730000 60.560001

# max 62.630001 65.180000

#

#

# LCID

# --------------------

# Low High

# mean 46.442539 51.811538

# min 39.341000 45.000000

# max 50.709999 57.750000

#

#

# RIVN

# --------------------

# Low High

# mean 119.150000 135.309230

# min 95.199997 114.500000

# max 153.779999 179.470001

- when we tried calculating the mean of the closing price earlier -

- when we did

car_stocks.groupby('Symbol'), we got back a dataframe group by object - when we added a

car_stocks.groupby('Symbol')['Close'], we got back a series group by object - we finally called

car_stocks.groupby('Symbol')['Close'].mean() to get back the mean of closing price for each symbol (i.e. stock)

- if we would have called mean on the dataframe group by object directly, we would have gotten back a dataframe -

car_stocks.groupby('Symbol').mean()

# Open High Low

# Symbol

# GM 61.937693 63.129231 61.051539

# LCID 48.761538 51.811538 46.442539

# RIVN 127.710000 135.309230 119.150000

- split, apply, combine - this is a workflow. going back to the closing price mean by stock example -

- we split into different parts - e.g. forming groups using groupby

- we then apply a function on each of the parts - e.g. performing a mean on each of these groups individually

- we finally combine the results from each of these parts - we get back a series containing means for each of the group

- we can also run multiple aggregation functions at once - below, we run it on both dataframe group by object and series group by object. running it on the dataframe group by object results in hierarchical columns -

car_stocks.groupby('Symbol')['Close'].agg(['mean', 'min', 'max'])

# mean min max

# Symbol

# GM 62.164615 59.270000 64.610001

# LCID 49.829231 40.750000 55.520000

# RIVN 127.523077 100.730003 172.009995

car_stocks.groupby('Symbol').agg(['mean', 'min', 'max'])

# Open High Low

# mean min max mean min max mean min max

# Symbol

# GM 61.937693 57.849998 64.330002 63.129231 60.560001 65.180000 61.051539 57.730000 62.630001

# LCID 48.761538 42.299999 56.200001 51.811538 45.000000 57.750000 46.442539 39.341000 50.709999

# RIVN 127.710000 106.750000 163.800003 135.309230 114.500000 179.470001 119.150000 95.199997 153.779999

- we can go more granular as well - we can run specific aggregation functions for specific columns as well -

car_stocks.groupby('Symbol').agg({ 'Open': ['min', 'max'], 'Close': ['mean'] })

# Open Close

# min max mean

# Symbol

# GM 57.849998 64.330002 62.164615

# LCID 42.299999 56.200001 49.829231

# RIVN 106.750000 163.800003 127.523077

- we can provide custom functions to agg as well - understand that this could very well have been a function from a library, and we would just have to pass its reference -

def range(x):

return x.max() - x.min()

car_stocks.groupby('Symbol')['Open'].agg(range)

# Symbol

# GM 6.480004

# LCID 13.900002

# RIVN 57.050003

- x is a pandas series, and range is called for every group - for all open prices for a particular stock, one at a time

- another example - this time, our custom aggregation function is called for multiple attributes, but everything is still the same. just that the output changes from a series to a dataframe, but the aggregation function is still called on a per attribute, per group basis

def count_nulls(x):

return len(x) - x.count()

titanic.groupby('pclass').agg(count_nulls)

# survived age sex

# pclass

# 1 0 39 0

# 2 0 16 0

# 3 0 208 0

- named aggregations - we just saw nested columns above, when we try to do multiple aggregations on multiple columns at once. this can make accessing data more complicated, since we would have to use hierarchical columns. in general, we might want to give a custom name to the result of our aggregation. we can do so using named aggregations -

car_stocks.groupby('Symbol').agg(

close_avg=('Close', 'mean'),

close_max=('Close', 'max'),

)

# close_avg close_max

# Symbol

# GM 62.164615 64.610001

# LCID 49.829231 55.520000

# RIVN 127.523077 172.009995

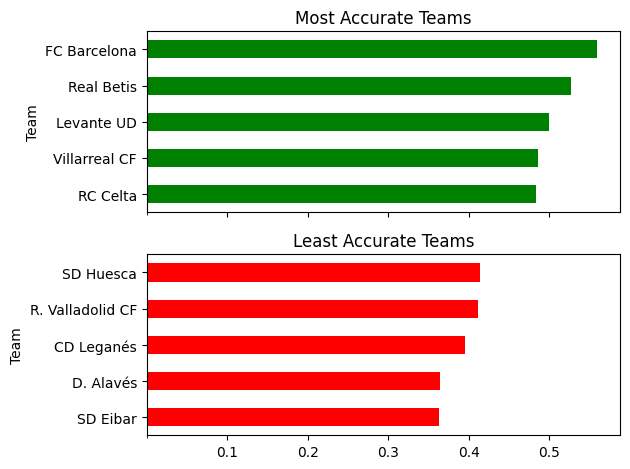

- example - we have statisctics on a per player basis for laliga, having columns for team name, shots taken, shots on target

- we would like to generate the plot below - x axis of the plot is shared

- generating the relevant data -

- first, we find total shots and shots on target by a team

- for this, we group by team, and perform sum aggregations for shots and shots on target

- we calculate accuracy using these two

- finally, we sort the data based on accuracy

team_stats = laliga.groupby('Team').agg(

total=('Shots', 'sum'),

on_target=('Shots on target', 'sum')

)

team_stats['accuracy'] = team_stats['on_target'] / team_stats['total']

team_stats.sort_values(['accuracy'], inplace=True)

team_stats

# total on_target accuracy

# Team

# SD Eibar 422 153 0.362559

# D. Alavés 299 109 0.364548

# CD Leganés 334 132 0.395210

# R. Valladolid CF 319 131 0.410658

# SD Huesca 343 142 0.413994

- generating the plot -

- most accurate teams - top 5 rows, least accurate teams - bottom 5. use head and tail to obtain them

- we have entirely different pandas plots that we would like to plot on the same figure on different axes. so, we use subplots. subplots can apart from dimensions, receive the sharex parameter

- note how we pass the axes received from subplots to plot

- we can set the xticks on (any) axes i guess

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 1, sharex=True)

team_stats.tail(5).plot(kind='barh', y='accuracy', ax=axes[0], legend=False, title='Most Accurate Teams', color='green')

team_stats.head(5).plot(kind='barh', y='accuracy', ax=axes[1], legend=False, title='Least Accurate Teams', color='red')

axes[0].set_xticks([0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5])

plt.tight_layout()

- we discuss hierarchical indexing next, but we can group by levels of hierarchical indices as well. we need to specify the levels keyword argument for that

state_pops

# population

# state year

# AK 1990 553290.0

# 1991 570193.0

# 1992 588736.0

# ... ... ...

# WY 2009 559851.0

# 2010 564222.0

# 2011 567329.0

state_pops.groupby(level=['year']).sum()

# year

# 1990 499245628.0

# 1991 505961884.0

# ...

# 2012 631398915.0

# 2013 635872764.0

- note - we specify name in this case, but we could have specified the level - 0, 1 etc as well

- if we see, the components of the hierarchical index are named, so specifying their names directly without the level keyword argument inside of groupby would have worked as well

state_pops.groupby('year').sum()

# year

# 1990 499245628.0

# 1991 505961884.0

# ...

# 2012 631398915.0

# 2013 635872764.0

- summary -

- we saw grouping using attributes by now

- but then we might want to group by index / components of hierachical index as well

- hence we could use the level keyword argument

- but then, we could use the same syntax as attributes for indices as well i.e. omit the level keyword argument

- also called multi indexing

- when we group by a single column, we get the following result -

mean_by_sex = titanic.groupby('sex')['age'].mean()

mean_by_sex.index

# Index(['female', 'male'], dtype='object', name='sex')

mean_by_sex

# sex

# female 28.687071

# male 30.585233

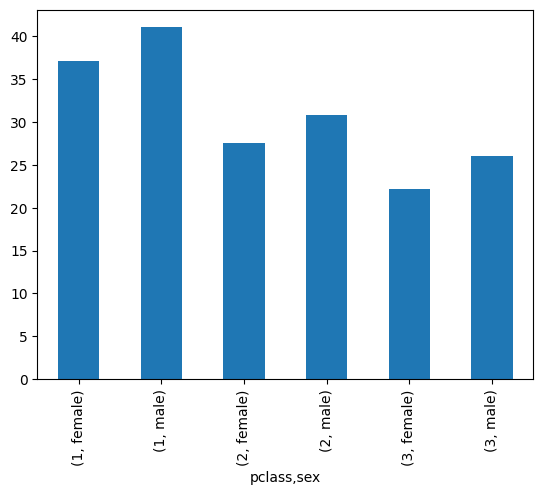

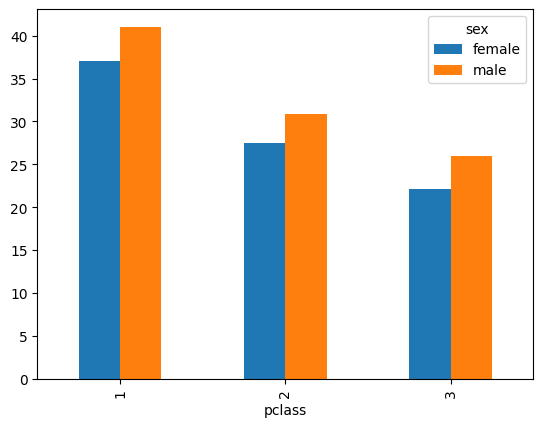

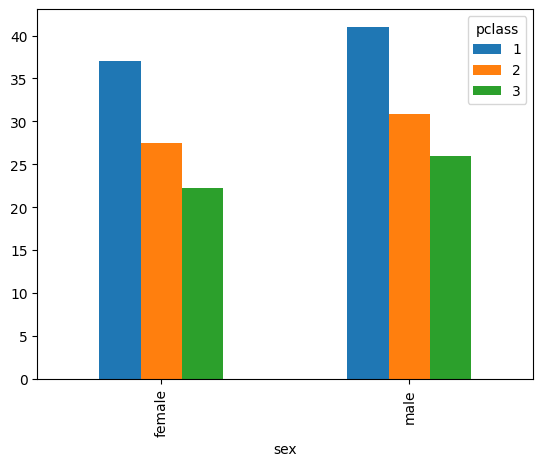

- however, when we group by multiple columns, we get the following result -

mean_by_pclass_and_sex = titanic.groupby(['pclass', 'sex'])['age'].mean()

mean_by_pclass_and_sex.index

# MultiIndex([(1, 'female'),

# (1, 'male'),

# (2, 'female'),

# (2, 'male'),

# (3, 'female'),

# (3, 'male')],

# names=['pclass', 'sex'])

mean_by_pclass_and_sex

# pclass sex

# 1 female 37.037594

# male 41.029250

# 2 female 27.499191

# male 30.815401

# 3 female 22.185307

# male 25.962273

- so, labels instead of being a plain index are now multi index

- above, we showed a multi index with a series, below is an example of a multi index with a dataframe. the index in this case is the same as the one we got when doing a mean of age, only the entire data structure changes from a series to a dataframe

titanic.groupby(['pclass', 'sex']).mean(numeric_only=True)

# survived age sibsp parch fare

# pclass sex

# 1 female 0.965278 37.037594 0.555556 0.472222 37.037594

# male 0.340782 41.029250 0.340782 0.279330 41.029250

# 2 female 0.886792 27.499191 0.500000 0.650943 27.499191

# male 0.146199 30.815401 0.327485 0.192982 30.815401

# 3 female 0.490741 22.185307 0.791667 0.731481 22.185307

# male 0.152130 25.962273 0.470588 0.255578 25.962273

- typically when seting up an index, we want it to -

- be unique - having the same index for multiple rows in a dataframe does not give an error. but, it is typically not advisable - e.g. loc would give us multiple rows

- make our data easily accessible - use for e.g. semantic index / natural key

- imagine we have the following dataframe -

state_pops = pd.read_csv('data/state_pops.csv')

state_pops

# state year population

# 0 AL 2012 4817528.0

# 1 AL 2010 4785570.0

# ... ... ... ...

# 1270 USA 2011 311582564.0

# 1271 USA 2012 313873685.0

- we can set up a custom hierarchical index for this dataset

state_pops.set_index(['state', 'year'], inplace=True)

state_pops

# population

# state year

# AL 2012 4817528.0

# 2010 4785570.0

# 2011 4801627.0

# USA 2013 316128839.0

# 2009 306771529.0

# 2010 309326295.0

- if we try sorting the index, by default, the data is sorted in the order of levels - e.g. the data is sorted first by state, and for a state, the rows are sorted by years

state_pops.sort_index()

# population

# state year

# AK 1990 553290.0

# 1991 570193.0

# 1992 588736.0

# WY 2009 559851.0

# 2010 564222.0

# 2011 567329.0

- assume we want to sort the data by years only. so, all the data for the lowest year should come first and so on. we can do the below -

state_pops.sort_index(level=1)

# population

# state year

# AK 1990 553290.0

# AL 1990 4050055.0

# ... ... ...

# WV 2013 1854304.0

# WY 2013 582658.0

- finally, assume we would like to sort in ascending order of state but then descending order of year. we can do the below -

state_pops.sort_index(level=[0, 1], ascending=[True, False])

# population

# state year

# AK 2013 735132.0

# 2012 730307.0

# ... ... ...

# WY 1994 480283.0

# 1993 473081.0

- finally - we were using numbers for levels till now, but names are supported as well - e.g. we can use

state_pops.sort_index(level=['year'], inplace=True) - indexing - behavior around slicing etc is pretty similar to what we studied here, just that we need to be wary of levels

- accessing by the first level only - we get back a dataframe, and not a series

state_pops.loc['WY']

# population

# year

# 1990 453690.0

# 1991 459260.0

# 1992 466251.0

- accessing by all levels - we get back a series, where the indices are the columns. we need to provide a tuple with the values for all the levels.

state_pops.loc[('WY', 2013)]

# population 582658.0

- note - we can still use slicing etc when using tuples -

state_pops.loc[('WY', 2010) : ('WY', 2013)]

# population

# state year

# WY 2010 564222.0

# 2011 567329.0

# 2012 576626.0

# 2013 582658.0

- till now, we saw accessing using the 1st level and all levels. what if we would like to access using some intermediate level(s)?

- first, recall from updating, if we have a normal dataframe without the hierarchical indexing, we would use loc as follows (remember that

: by itself means everything - all indices / all columns depending on where it is used) -titanic

# pclass survived

# 0 1 1

# 1 1 1

# 2 1 0

titanic.loc[:, 'pclass']

# 0 1

# 1 1

# 2 1

titanic.loc[:, ['pclass']]

# pclass

# 0 1

# 1 1

# 2 1

titanic.loc[:, :]

# pclass survived

# 0 1 1

# 1 1 1

# 2 1 0

- so, extending on the above for a dataframe with hierarchical indexing, my understanding is we will need extra commas for the extra levels. so, back to our original question of how to access using selective levels when we have hierarchical indexing - we can for e.g. just use

: for the levels for which we want everything, and specify singular values using a, specify ranges like a:b, specify selected values using [a,b] etc based on use casestate_pops.loc[:,:,]

# population

# state year

# AK 1990 553290.0

# 1991 570193.0

# ... ... ...

# WY 2009 559851.0

# 2010 564222.0

# since we specify only one year

# pandas would eliminate this column altogether

state_pops.loc[:,2010,:]

# population

# state

# AK 713868.0

# AL 4785570.0

# AR 2922280.0

# AZ 6408790.0

# CA 37333601.0

# CO 5048196.0

state_pops.loc[:,[2010,2013],:]

# population

# state year

# AK 2010 713868.0

# 2013 735132.0

# AL 2010 4785570.0

# 2013 4833722.0

# ... ... ...

# WV 2010 1854146.0

# 2013 1854304.0

# WY 2010 564222.0

# 2013 582658.0

state_pops.loc[:,2010:2012,:]

# population

# state year

# AK 2010 713868.0

# 2011 723375.0

# 2012 730307.0

# AL 2010 4785570.0

# 2011 4801627.0

# ... ... ...

# WV 2011 1855184.0

# 2012 1856680.0

# WY 2010 564222.0

# 2011 567329.0

# 2012 576626.0

- cross section or

xs is another useful alternative to the loc syntax when using hierarhcical indexing. i will stick to loc for now though

- for accessing all values of a column, we use the syntax

df['col_name'], but this would not work for index column(s) - to access the values of an index when a dataframe does not have hierarchical indexing, we use

df.index - what if we wanted to access the components of a hierarchical index? assume our dataframe looks like this -

# population

# state year

# AK 1990 553290.0

# 1991 570193.0

# 1992 588736.0

# ... ... ...

# WY 2009 559851.0

# 2010 564222.0

# 2011 567329.0

- to access the index values of a particular position, we can use the following -

state_pops.index[0] # ('AK', 1990)

state_pops.index[1] # ('AK', 1991)

state_pops.index[2] # ('AK', 1992)

- to access all the index values, we have two options according too my understanding -

- option 1 - access via the levels property. but, it will only have the unique values - it would not be an accurate representation of our data

state_pops.index.levels

# FrozenList([['AK', 'AL', 'AR', 'AZ', 'CA', 'CO', 'CT', 'DC', 'DE', 'FL', 'GA', 'HI', 'VT', 'WA', 'WI', 'WV', 'WY'],

# [1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013]]

state_pops.index.levels[0]

# Index(['AK', 'AL', 'AR', 'AZ', 'CA', 'CO', 'CT', 'DC', 'DE', 'FL', 'GA', 'HI',

# 'VT', 'WA', 'WI', 'WV', 'WY']

state_pops.index.levels[1]

# Index([1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001,

# 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013],

- option 2 - accessing via get level values. usecase - recall how we performed filtering using column attributes -

df[df['col'] > 500]. we can do the same when using option 2. our conditions will look like this now - df[df.index.get_level_values(1) > 500]state_pops.index.get_level_values(0)

# Index(['AK', 'AK', 'AK', 'AK', 'AK', 'AK', 'AK', 'AK', 'AK', 'AK',

# ...

# 'WY', 'WY', 'WY', 'WY', 'WY', 'WY', 'WY', 'WY', 'WY', 'WY'],

state_pops.index.get_level_values(1)[:50]

# Index([1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001,

# 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013,

# 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001,

# 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013,

# 1990, 1991],

- concat - concatenate series / dataframes

import pandas as pd

s1 = pd.Series(['a', 'b', 'c'])

s2 = pd.Series(['d', 'e', 'f'])

pd.concat([s1, s2])

# 0 a

# 1 b

# 2 c

# 0 d

# 1 e

# 2 f

- we can set ignore index to true if our index was not semantic. notice the difference in the index values above and below

pd.concat([s1, s2], ignore_index=True)

# 0 a

# 1 b

# 2 c

# 3 d

# 4 e

# 5 f

- we can concatenate by index follows -

pd.concat([s1, s2], axis='columns')

# 0 1

# 0 a d

# 1 b e

# 2 c f

- however, this is not just putting side by side - it is actually using the index values to join. e.g. -

food = pd.Series(

data=['avocado', 'blueberry', 'cucumber'],

index=['a', 'b', 'c']

)

animals = pd.Series(

data=['dolphin', 'bear', 'chameleon'],

index=['d', 'b', 'c']

)

pd.concat([food, animals], axis='columns')

# 0 1

# a avocado NaN

# b blueberry bear

# c cucumber chameleon

# d NaN dolphin

- notice the column names would be numeric by default. we can change that using the keys keyword argument

pd.concat([food, animals], axis='columns', keys=['khana', 'janwar'])

# khana janwar

# a avocado NaN

# b blueberry bear

# c cucumber chameleon

# d NaN dolphin

- note - we saw NaN earlier, because the join is outer by default. we can set it to inner as well

pd.concat([food, animals], axis='columns', join='inner')

# 0 1

# b blueberry bear

# c cucumber chameleon

- till now, we were combining series. now, we combine dataframes. assume we have the data below -

harvest_21 = pd.DataFrame(

[['potatoes', 9001], ['garlic', 1350], ['onions', 87511]],

columns=['crop', 'qty']

)

# crop qty

# 0 potatoes 9001

# 1 garlic 1350

# 2 onions 87511

harvest_22 = pd.DataFrame(

[[1600, 'garlic'], [560, 'spinach'], [999, 'turnips'], [1000, 'onions']],

columns=['qty', 'crop']

)

# qty crop

# 0 1600 garlic

# 1 560 spinach

# 2 999 turnips

# 3 1000 onions

- when we try to concatenate the two dataframes, we get the below. note - even though the ordering of columns for the two dataframes were different, pandas combines them using the column names

pd.concat([harvest_21, harvest_22])

# crop qty

# 0 potatoes 9001

# 1 garlic 1350

# 2 onions 87511

# 0 garlic 1600

# 1 spinach 560

# 2 turnips 999

# 3 onions 1000

- assume we have another dataframe with an extra column -

harvest_23 = pd.DataFrame(

[['potatoes', 900, 500], ['garlic', 1350, 1200], ['onions', 875, 950]],

columns=['crop', 'qty', 'profit']

)

# crop qty profit

# 0 potatoes 900 500

# 1 garlic 1350 1200

# 2 onions 875 950

- if we now try concatenating two dataframes with difference in columns, we get NaN for the missing columns

pd.concat([harvest_22, harvest_23])

# qty crop profit

# 0 1600 garlic NaN

# 1 560 spinach NaN

# 2 999 turnips NaN

# 3 1000 onions NaN

# 0 900 potatoes 500.0

# 1 1350 garlic 1200.0

# 2 875 onions 950.0

- to change this behavior, we can specify inner for the join type

pd.concat([harvest_22, harvest_23], join='inner')

# qty crop

# 0 1600 garlic

# 1 560 spinach

# 2 999 turnips

# 3 1000 onions

# 0 900 potatoes

# 1 1350 garlic

# 2 875 onions

- the ignore index parameter behaves in the same way, already discussed

- we can also set up hierarchical indexing using the keys parameter - e.g. it is typical to analyze files for different years simultaneously, and we might want to encode this information in the form of a hierarchical index for the dataframe

pd.concat([harvest_21, harvest_22, harvest_23], join='inner', keys=[2021, 2022, 2023])

# crop qty

# 2021 0 potatoes 9001

# 1 garlic 1350

# 2 onions 87511

# 2022 0 garlic 1600

# 1 spinach 560

# 2 turnips 999

# 3 onions 1000

# 2023 0 potatoes 900

# 1 garlic 1350

# 2 onions 875

- its closer to a database style join and is more flexible than concat since we can combine using columns instead of relying on the index

teams = pd.DataFrame(

[

["Suns", "Phoenix", 20, 4],

["Mavericks", "Dallas", 11, 12],

["Rockets", "Houston", 7, 16],

["Nuggets", "Denver", 11, 12]

],

columns=["team", "city", "wins", "losses"]

)

# team city wins losses

# 0 Suns Phoenix 20 4

# 1 Mavericks Dallas 11 12

# 2 Rockets Houston 7 16

# 3 Nuggets Denver 11 12

cities = pd.DataFrame(

[

["Houston", "Texas", 2310000],

["Phoenix", "Arizona", 1630000],

["San Diego", "California", 1410000],

["Dallas", "Texas", 1310000]

],

columns=["city", "state", "population"]

)

# city state population

# 0 Houston Texas 2310000

# 1 Phoenix Arizona 1630000

# 2 San Diego California 1410000

# 3 Dallas Texas 1310000

- now, if we perform a merge, an inner join is performed using the common column name automatically -

teams.merge(cities)

# team city wins losses state population

# 0 Suns Phoenix 20 4 Arizona 1630000

# 1 Mavericks Dallas 11 12 Texas 1310000

# 2 Rockets Houston 7 16 Texas 2310000

- we can set the how parameter for join type. as we saw, it is inner by default, but we can set it to outer, left, right, etc

teams.merge(cities, how='left')

# team city wins losses state population

# 0 Suns Phoenix 20 4 Arizona 1630000.0

# 1 Mavericks Dallas 11 12 Texas 1310000.0

# 2 Rockets Houston 7 16 Texas 2310000.0

# 3 Nuggets Denver 11 12 NaN NaN

- cross join is also there - all rows of one dataframe with all rows of the other dataframe

- by default, the same column name was used explicitly. we can however, specify the column(s) explicitly using the on keyword argument

teams.merge(cities, on='city')

- note - we can specify multiple columns for the on parameter as well based on use case

- what if the two dataframes have similar column names, and are not being used for joining? pandas will suffix them with _x and _y by default. e.g. below, the name column is being used for the join, so it is only present once. however, the score column is not, and therefore it is preset with a suffix

midterm = pd.DataFrame(

[['shameek', 42], ['colt', 45]],

columns=['name', 'score']

)

final = pd.DataFrame(

[['shameek', 85], ['colt', 97]],

columns=['name', 'score']

)

midterm.merge(final, on='name')

# name score_x score_y

# 0 shameek 42 85

# 1 colt 45 97

- we can however, specify the suffixes to append -

midterm.merge(final, on='name', suffixes=['_midterm', '_final'])

# name score_midterm score_final

# 0 shameek 42 85

# 1 colt 45 97

- also note how we had to specify on explicitly, otherwise both name and score would be used. since there is no data with the same value in both tables, we end up with an empty result set

- uses matplotlib underneath, and works well with pandas

- typically imported as sns

import seaborn as sns

- to play around with seaborn, we can use any of the datasets present here via load dataset. it returns the pandas dataframe

tips = sns.load_dataset('tips')

tips

# total_bill tip sex smoker day time size

# 0 16.99 1.01 Female No Sun Dinner 2

# 1 10.34 1.66 Male No Sun Dinner 3

# 2 21.01 3.50 Male No Sun Dinner 3

- note - for the default theme of sns to kick in which kind of looks good, run the following

sns.set_theme()

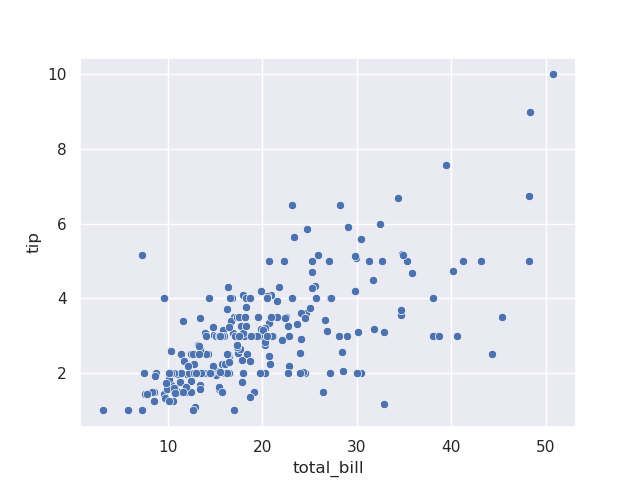

- for a scatterplot, we can do the following -

sns.scatterplot(tips, x='total_bill', y='tip')

- note - the exact above result could have been achieved without seaborn as well -

tips.plot(kind='scatter', x='total_bill', y='tip')

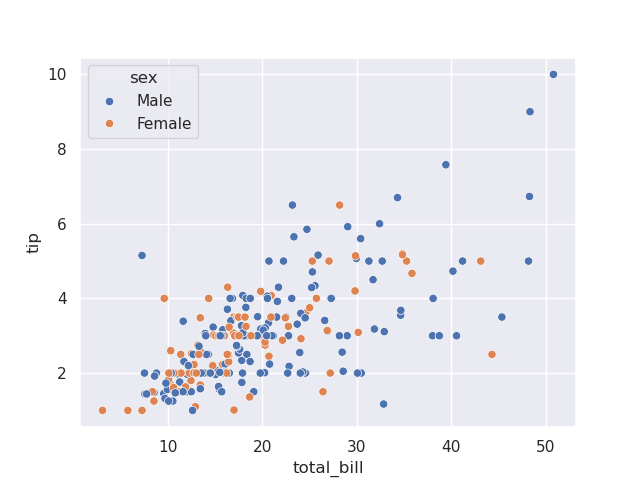

- but, now, look how we can simply pass hue for different scatter plots based on color on the same axes -

sns.scatterplot(tips, x='total_bill', y='tip', hue='sex')

- further, we can pass in style for different scatter plots based on marker on the same axes

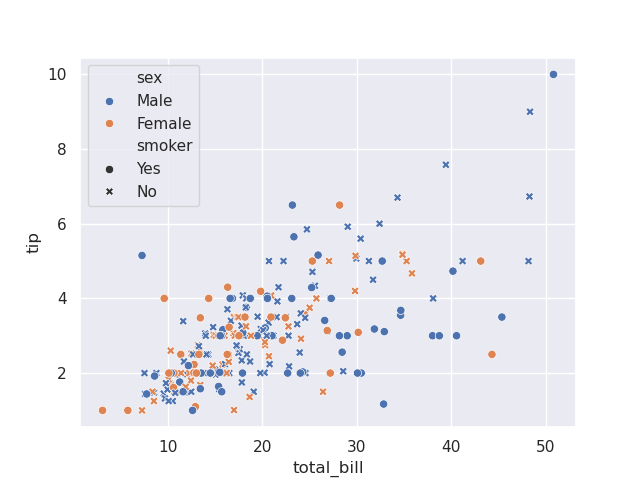

sns.scatterplot(tips, x='total_bill', y='tip', hue='sex', style='smoker')

- note - if we use the same column for hue and style, the marker and color both change, thus maybe improving readability

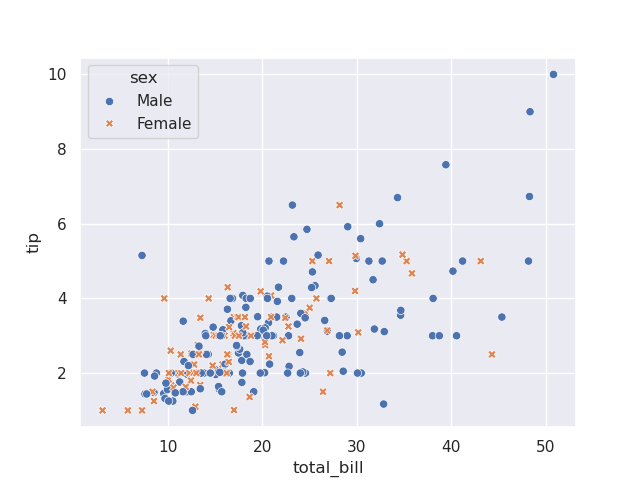

sns.scatterplot(tips, x='total_bill', y='tip', hue='sex', style='sex')

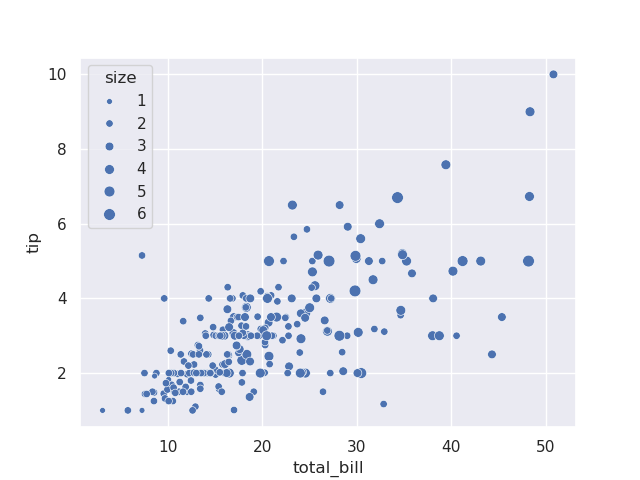

- e.g. assume tips have a size column, which represents the number of people together. we can add the size keyword argument, which changes the size of the marker

sns.scatterplot(tips, x='total_bill', y='tip', size='size')

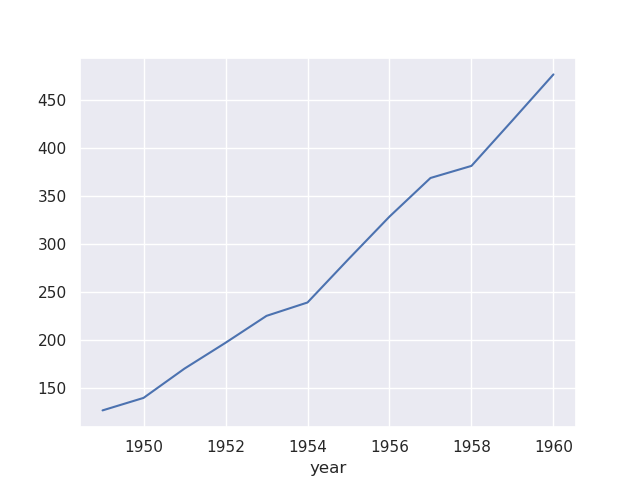

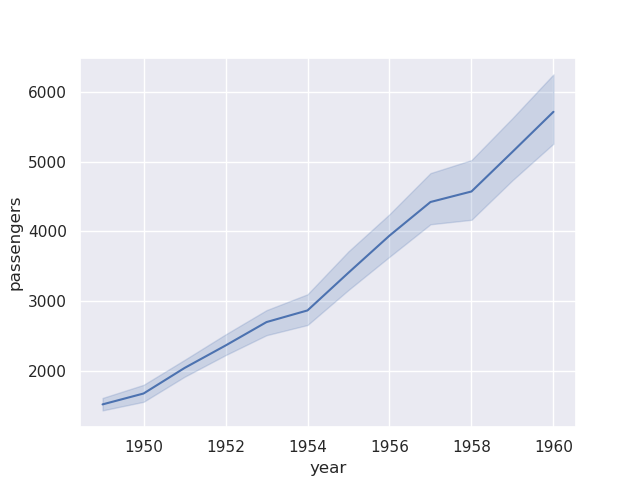

- assume we have a dataset for flights like so i.e. we have 12 records per year for each of the months -

flights = sns.load_dataset('flights')

flights

# year month passengers

# 0 1949 Jan 112

# 1 1949 Feb 118

# 2 1949 Mar 132

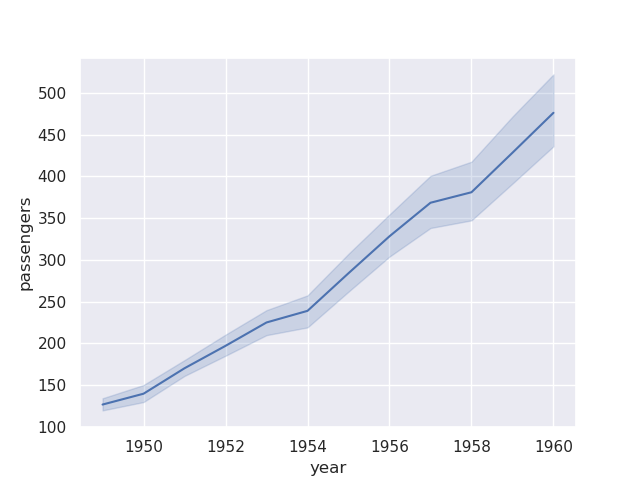

- e.g. we try to create a lineplot below. but, we do not specify how it should plot the multiple records that it gets for a passenger in a year. it plots using the estimator as mean by default

sns.lineplot(flights, x='year', y='passengers')

- if we wanted to achieve this ourselves using matplotlib, we would have to group it and then use the aggregation function like below -

flights.groupby('year')['passengers'].mean().plot()

- estimators are pandas functions. we can also provide a custom estimator, e.g.

sum as so -sns.lineplot(flights, x='year', y='passengers', estimator='sum')

- note how there is also a confidence interval that seaborn also adds to the plot. we can control its width, method, etc using error bar. setting it to None would remove it completely

sns.lineplot(flights, x='year', y='passengers', estimator='sum', errorbar=None)

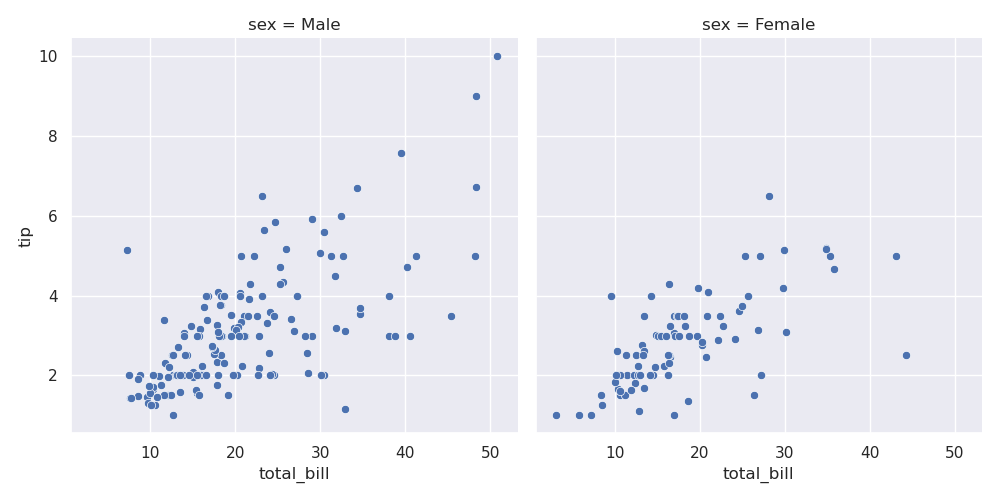

- my understanding - seaborn has two kinds of plots - figure level plots and axes level plots. the ones we saw above - lineplot and scatterplot are axes level plots their corresponding figure level plot is relplot or relational plot

# initial

sns.scatterplot(data=tips, x='total_bill', y='tip')

# using relplot

sns.relplot(data=tips, x='total_bill', y='tip', kind='scatter')

- but now, we can easily put different subplots / different axes on the same figure

- e.g. assume we would like to have different columns for the different values of sex

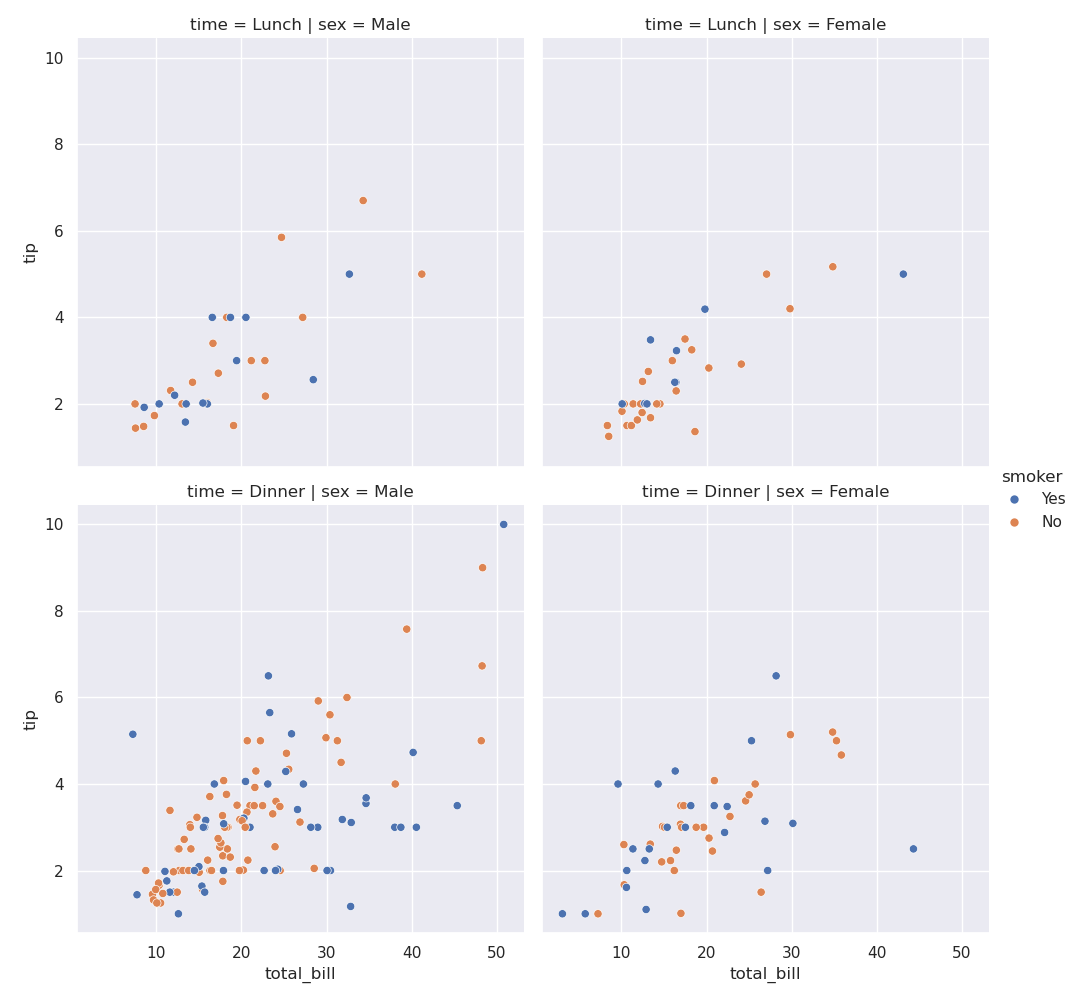

sns.relplot(data=tips, x='total_bill', y='tip', row='time', col='sex', hue='smoker')

- a more involved example. break into -

- columns using sex

- rows using time - lunch or dinner

- different colors for smokers and non smokers

sns.relplot(data=tips, x='total_bill', y='tip', row='time', col='sex', hue='smoker')

- controlling figure size for axes level plots - we make the figure call first

plt.figure(figsize=(4, 3))

sns.scatterplot(data=tips, x='total_bill', y='tip')

- controlling figure size for figure level plots - relplot creates a figure for us bts, so we cannot call the figure ourselves. instead, we control size of each facet i.e. subplot using height and aspect (ratio between height and width)

sns.relplot(data=tips, x='total_bill', y='tip', row='time', col='sex', hue='smoker', height=3, aspect=2)

- relation plots - relation between two things x and y

- distribution plots - distribution of data, e.g. histogram

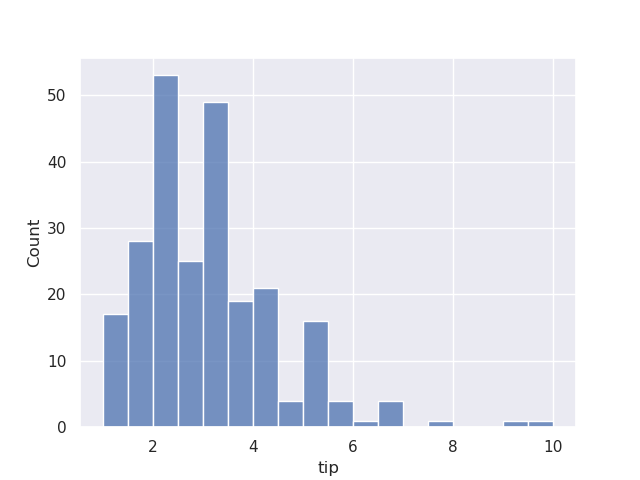

- histogram example - assume we try to visualize the tips dataset -

sns.histplot(data=tips, x='tip')

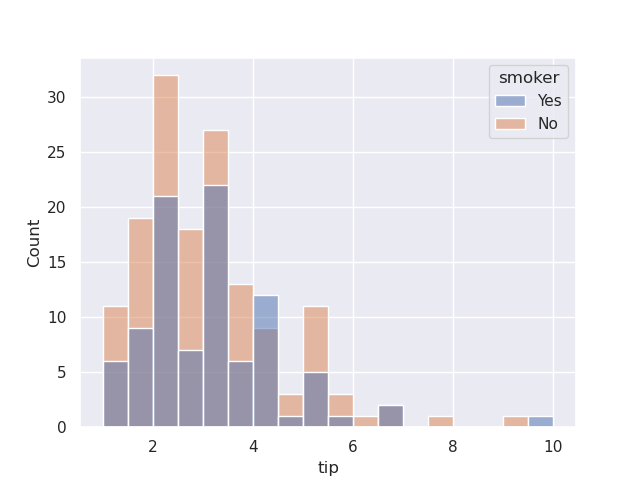

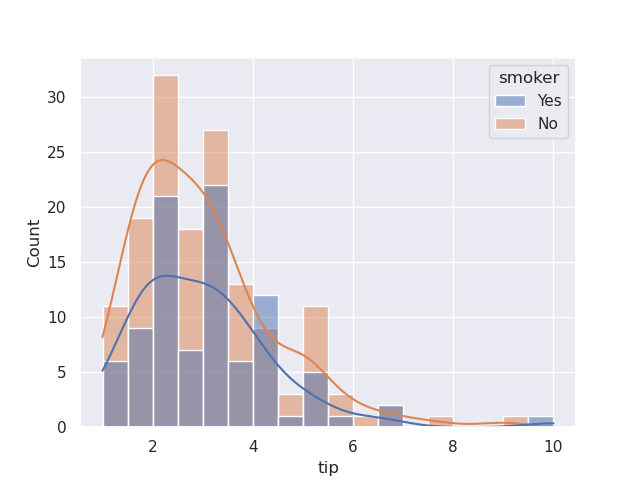

- if we use hue, by default, they would come one on top of another. the opacity is such that they are see through -

sns.histplot(data=tips, x='tip', hue='smoker')

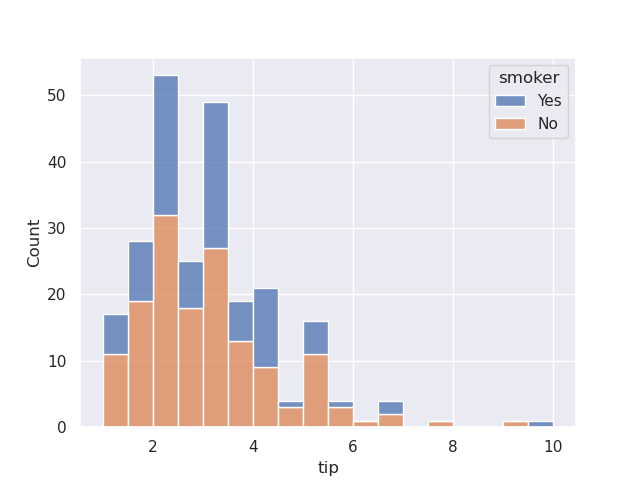

- we can configure it to be stacked instead of appearing one on top of another

sns.histplot(data=tips, x='tip', hue='smoker', multiple='stack')

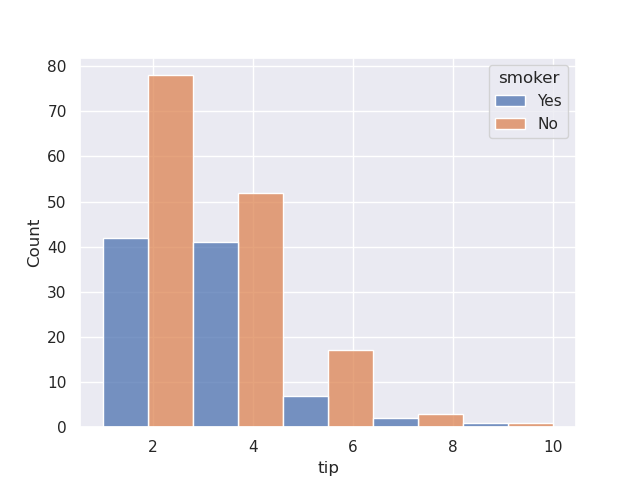

- we can also set multiple to be dodge, so that appear one beside another. note how i also configure bins in this case

sns.histplot(data=tips, x='tip', hue='smoker', multiple='dodge', bins=5)

- finally, we can add the kde curve to the histogram plot as well by setting kde to true

sns.histplot(data=tips, x='tip', hue='smoker', kde=True)

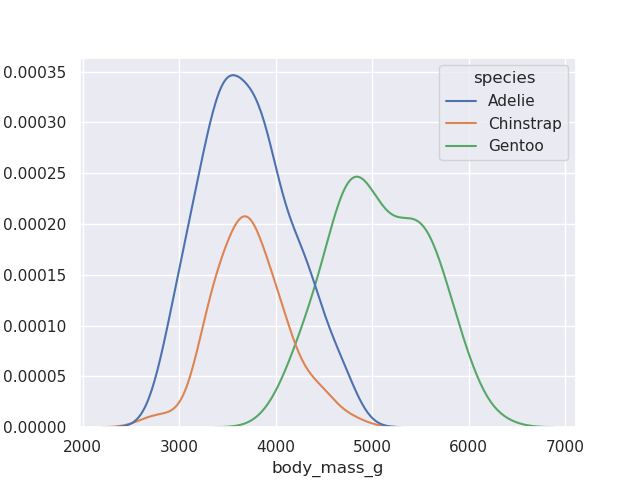

- above, we ovrlayed the kde curve on top of the histogram. however, we can add a standalone kde curve as well. below, we try to visualize the weights of different species of penguins simultaneously

sns.kdeplot(data=penguins, x='body_mass_g', hue='species')

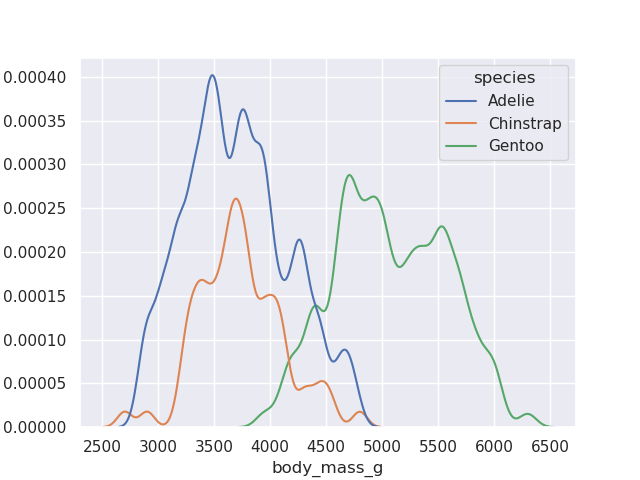

- finally, we can also configure the precision by adjusting the bandwidth

sns.kdeplot(data=penguins, x='body_mass_g', hue='species', bw_adjust=0.4)

- histograms / kde plots are also called as univariate distribution plots i.e. we only look at the distribution of a single feature

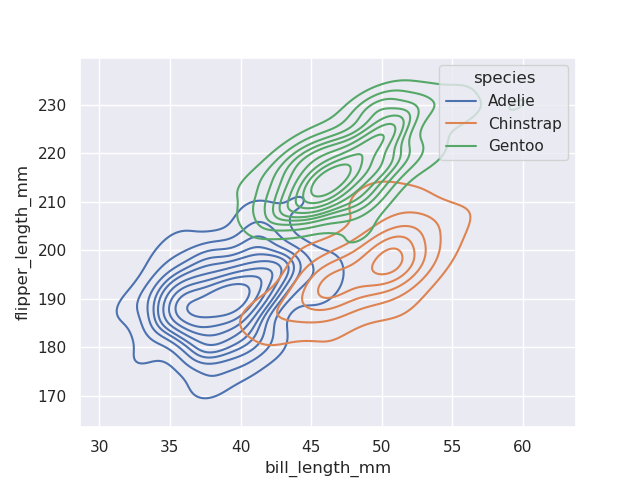

- we can look at bivariate distribution plots as well i.e. analyze two features at once, both on x and y axis

- kde bivariate distribution plots - try looking for smoother curves (like the hollow i believe?)

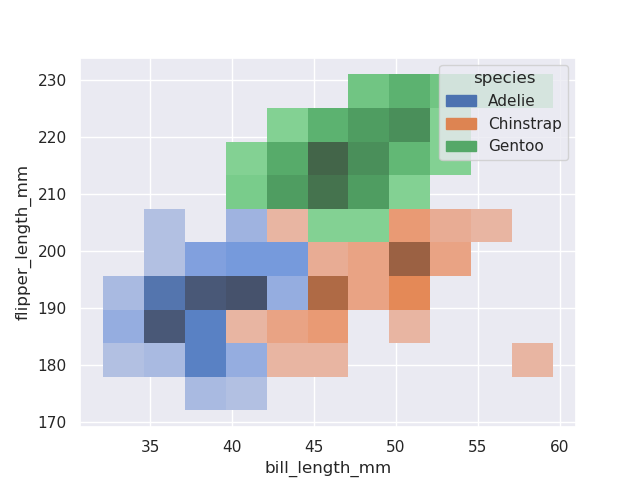

sns.kdeplot(data=penguins, x='bill_length_mm', y='flipper_length_mm', hue='species')

- histogram bivariate distribution plots - try looking for the concentrated coloring (like a heat map)

sns.histplot(data=penguins, x='bill_length_mm', y='flipper_length_mm', hue='species')

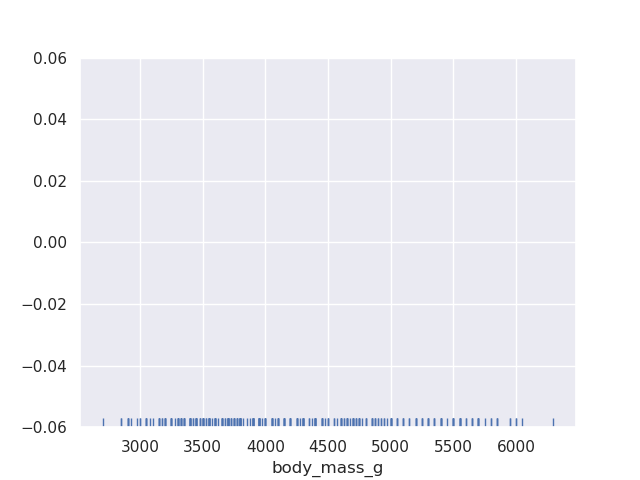

- rugplots - ticks along the x or y axis to show the presence of an observation

sns.rugplot(data=penguins, x='body_mass_g')

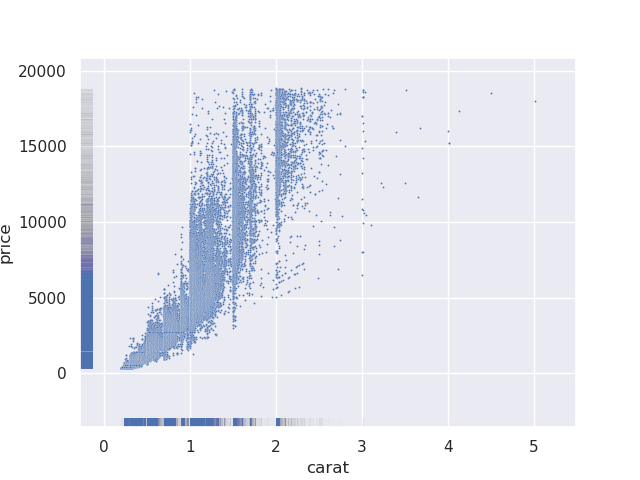

- this is not very useful by itself. because rugplots are useful when used with other plots. e.g. below, from our scatterplot, it is difficult to find out where the majority of the values lie, so we supplement it with a rugplot

sns.scatterplot(data=diamonds, x='carat', y='price', s=2)

sns.rugplot(data=diamonds, x='carat', y='price', alpha=0.005)

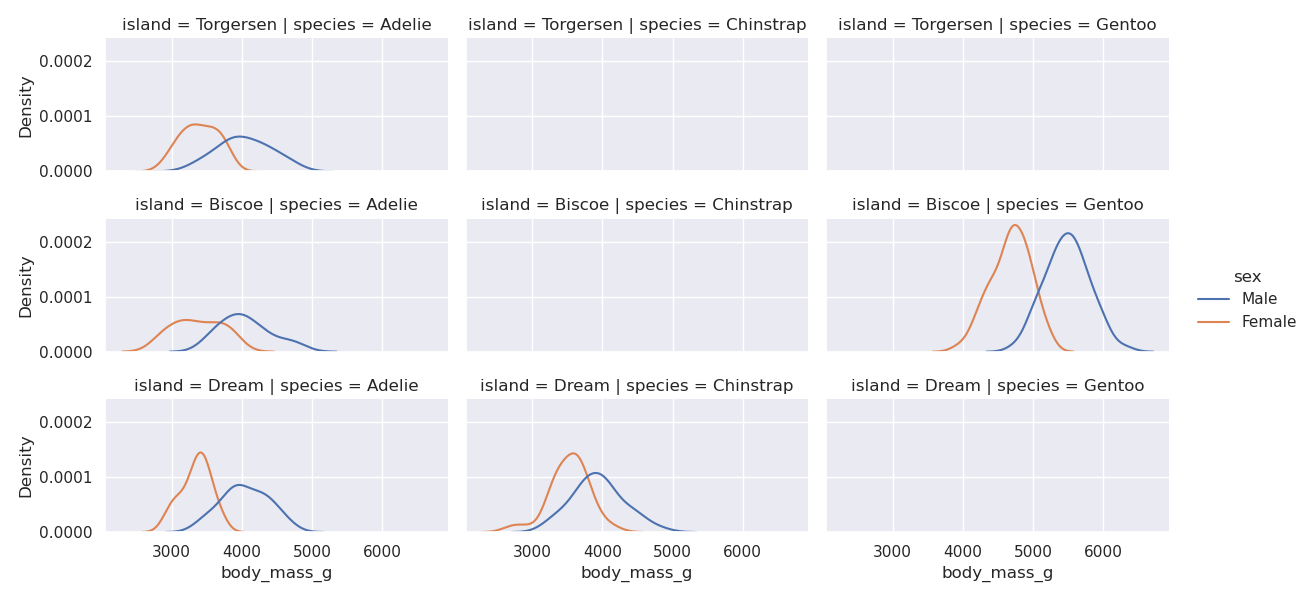

- we use displot for the figure level plot of distibution plots, no surprises here

sns.displot(data=penguins, kind='kde', x='body_mass_g', col='species', row='island', height=2, aspect=2, hue='sex')

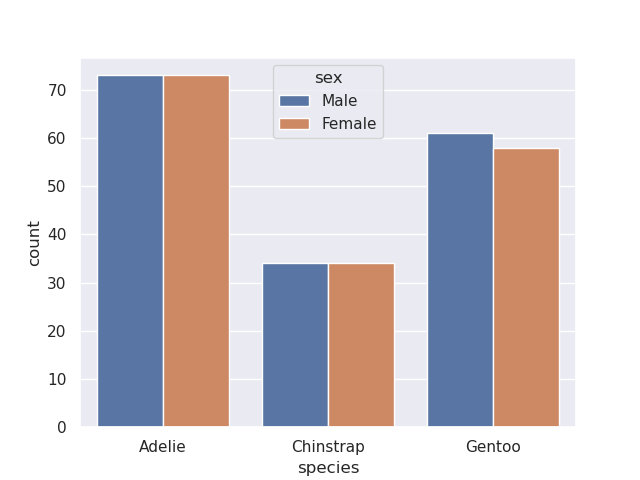

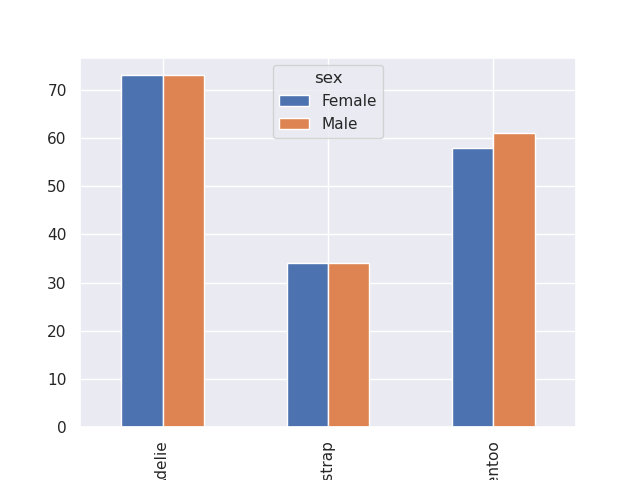

- count plot - displays count. but unlike histograms which typically used for numerical data, count plots are typically used for non numerical data

sns.countplot(data=penguins, x='species', hue='sex')

- to achieve something similar when using matplotlib by itself, i did the following -

penguins[['species', 'sex']].value_counts().unstack('sex').plot(kind='bar')

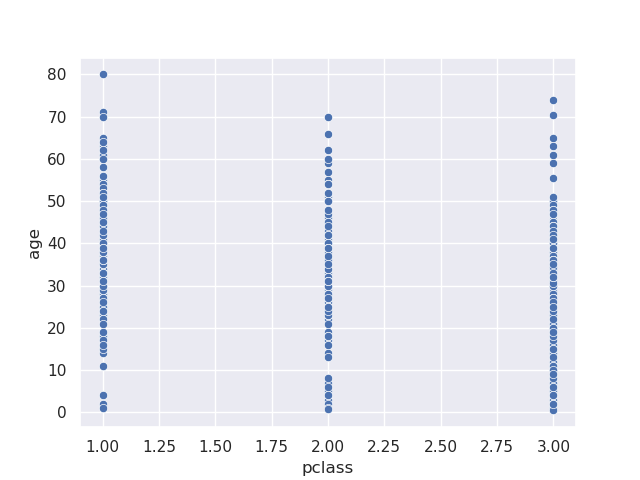

- issue - if we tried to make a scatterplot for categorical data - it would be hard to comment on the density -

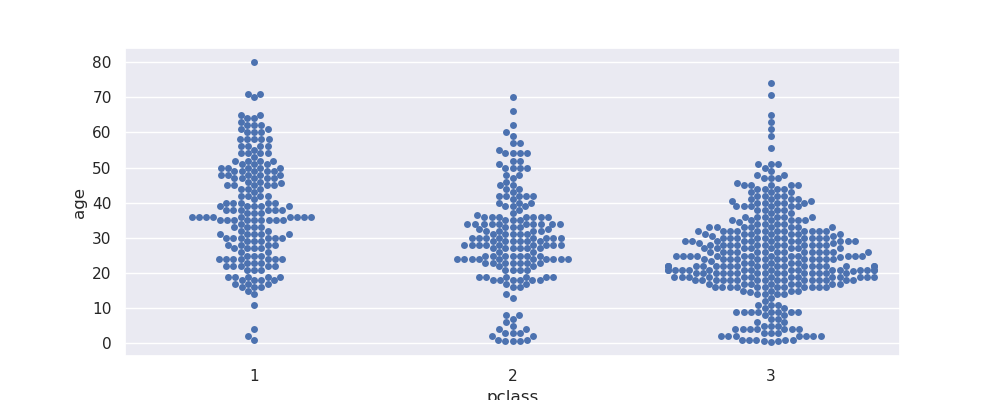

sns.scatterplot(data=titanic, x='pclass', y='age')

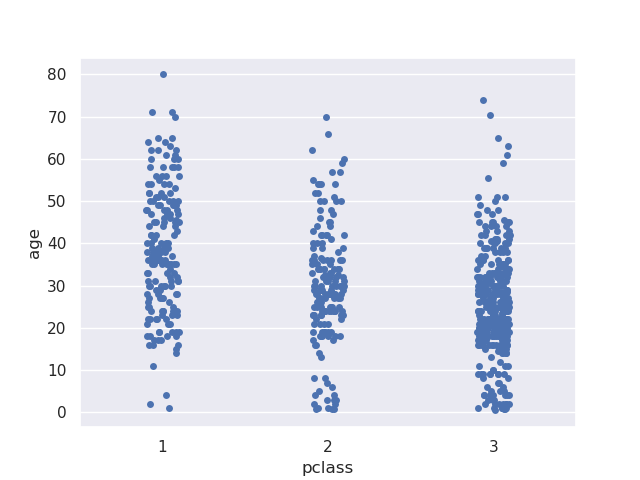

- solution 1 - we can use stripplot - it introduces a little bit of jitter to improve readability -

sns.stripplot(data=titanic, x='pclass', y='age')

- solution 2 - we can use swarmplot - it ensures points are non overlapping to improve readability. my understanding - use this only for smaller / sampled datasets, otherwise achieving this can become difficult

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 4))

sns.swarmplot(data=titanic, x='pclass', y='age')

- note how i had to adjust the figuresize, otherwise i get the warning -

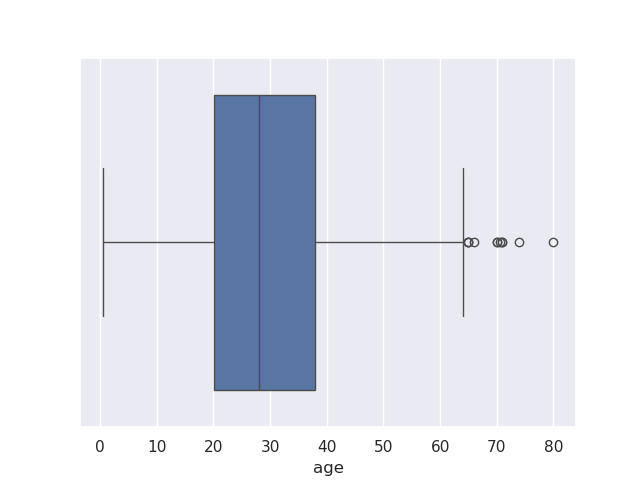

UserWarning: 15.2% of the points cannot be placed; you may want to decrease the size of the markers or use stripplot. - box plots - helps visualize distribution of categorical data easily. features -

- q1 represents the 25% value

- q3 represents the 75% value

- we have the median value plotted in between

- the range between q1 to q3 is called iqr or inter quartile range

- the lines surrounding iqr are called whiskers. they are placed relative to q1 and q3, and default to 1.5 i believe

- finally, we have outliers outside these whiskers

sns.boxplot(data=titanic, x='age')

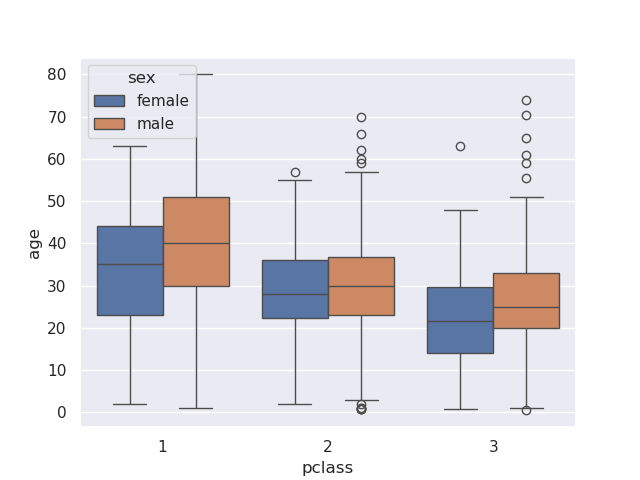

- using boxplot for categorical data -

sns.boxplot(data=titanic, x='pclass', y='age', hue='sex')

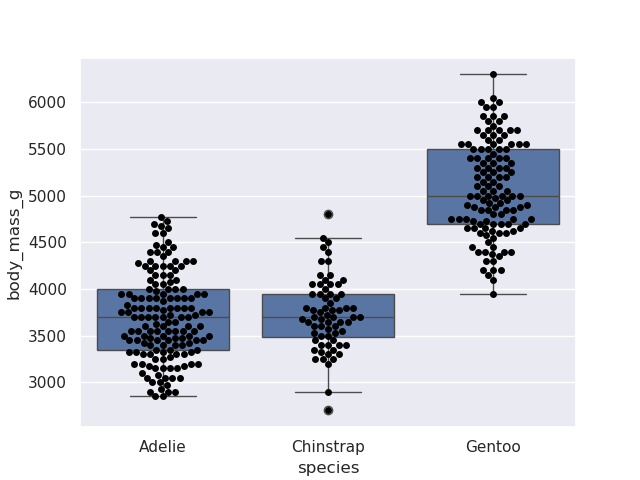

- combining boxplot and swarmplot. small reminder from matplotlib that they go into the same figure and axes since we do not call a

plt.figure() in betweensns.boxplot(data=penguins, y='body_mass_g', x='species')

sns.swarmplot(data=penguins, y='body_mass_g', x='species', color='black')

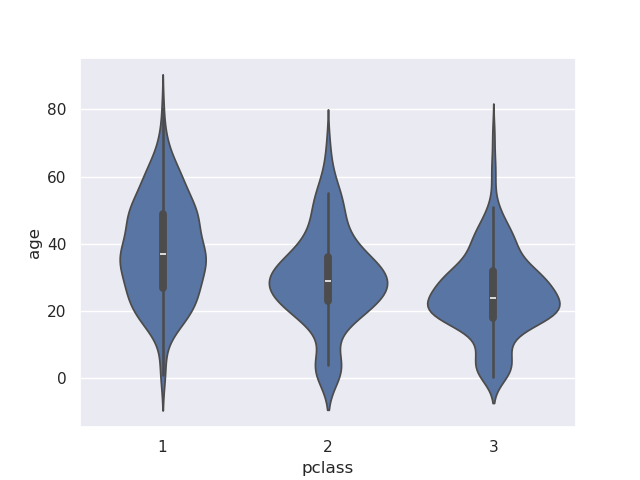

- violin plot - has the box plot at the center along with the kde curve. carefully look at the black line to see the median, inter quartile range and whiskers

sns.violinplot(data=titanic, x='pclass', y='age')

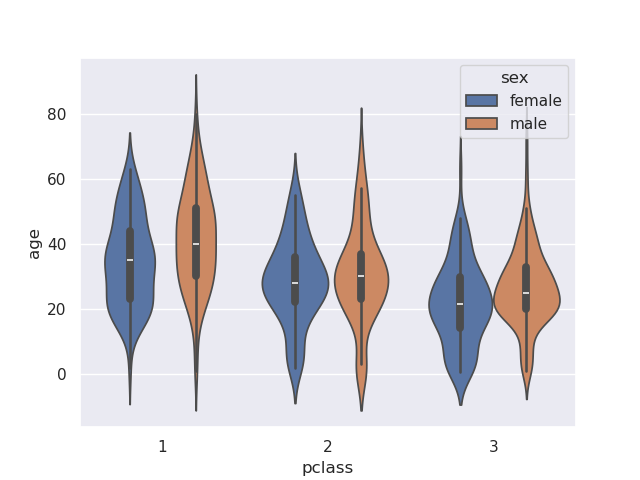

- note - if we add a hue, it creates different violin plots side by side

sns.violinplot(data=titanic, x='pclass', y='age', hue='sex')

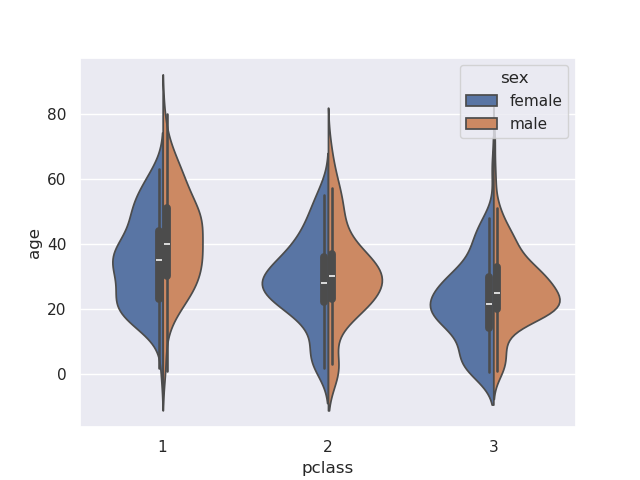

- we can however, change this behavior by providing the split parameter

sns.violinplot(data=titanic, x='pclass', y='age', hue='sex', split=True)

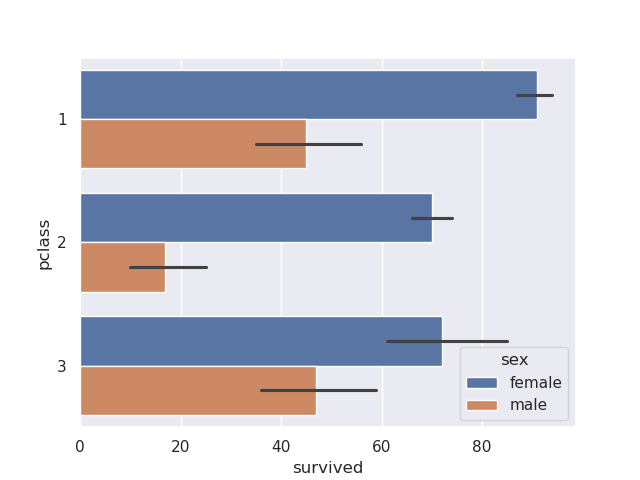

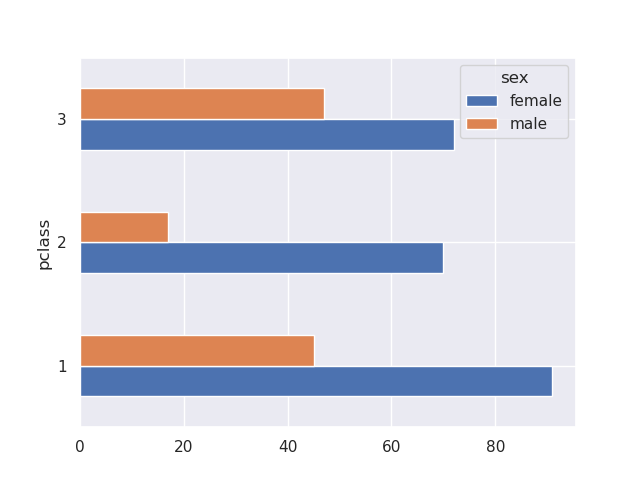

- bar plot - again, compare the difference from matplotib, where there is no calculation - it just plots, while seaborn grouping and using an estimator like we saw in line plots

sns.barplot(data=titanic, y='pclass', x='survived', hue='sex', estimator='sum', orient='h')

- the black line i believe helps with approximation and thus faster plotting and calculations

- plotting the same thing using matplotlib -

titanic.groupby(['pclass', 'sex'])['survived'].sum().unstack().plot(kind='barh')

- categorical plot - figure level plot, not bothering as there is nothing new

![]()

![]()

![]()