- example - car price prediction. also called “msrp” or “manufacturer suggested retail price”

- first, we go through the “data preparation” phase

- we standardize the column names by lowercasing and replacing spaces with underscores -

df.columns = df.columns.str.lower().str.replace(' ', '_')

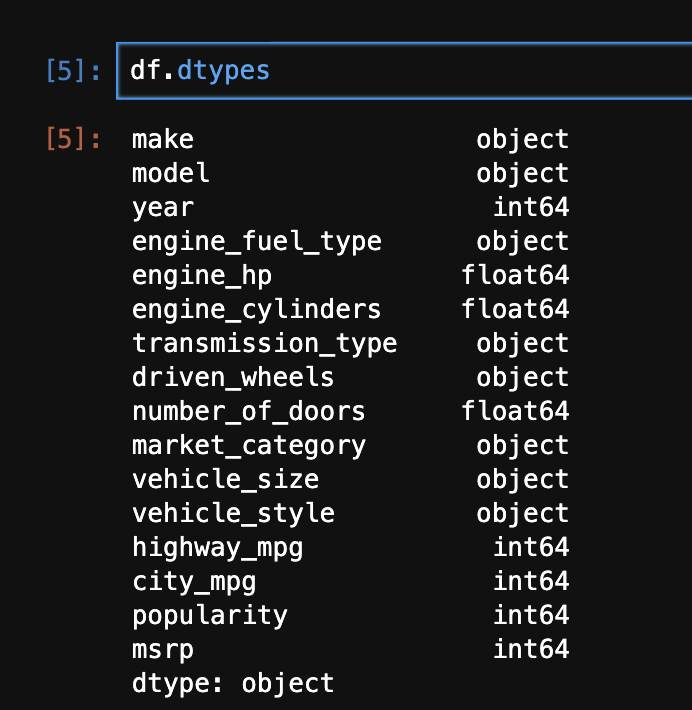

- next, we try to standardize the string columns of our dataframe as well. calling

dtypes on a dataframe returns us a pandas series, where the index is the column names, and the values are the types of the columns - hence, we use the below to standardize the string columns, by for e.g. lowercasing them -

str_cols = df.dtypes[df.dtypes == 'object'].index

for col in str_cols:

df[col] = df[col].str.lower()

- next, we perform some “exploratory data analysis”

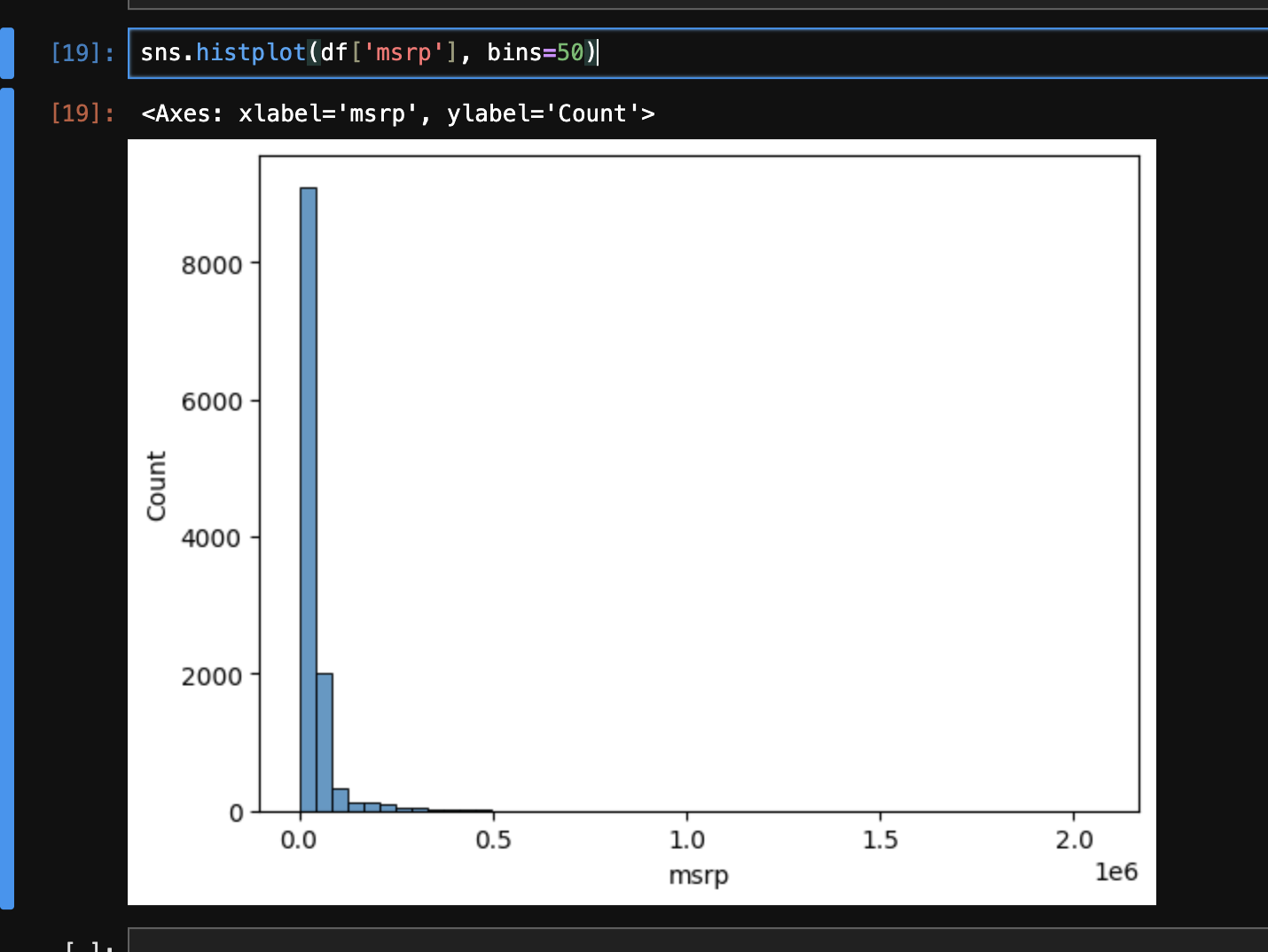

- when we try plotting the msrp, we see that its distribution is “skewed”. it is also called “long tail distribution”

- we can then use some techniques to verify our thesis, e.g. by plotting

sns.histplot(df[df['msrp'] > 500000]['msrp'], bins=50), we see that there are very few costly cars. this kind of distribution is not good for machine learning models - so, we apply the “logarithmic” transformation to it, as it makes the values more “compact”. it makes the distribution “normal”. see the example below to understand this -

np.log([1, 10, 1000, 1000000])

# array([ 0. , 2.30258509, 6.90775528, 13.81551056])

- log of 0 gives us a

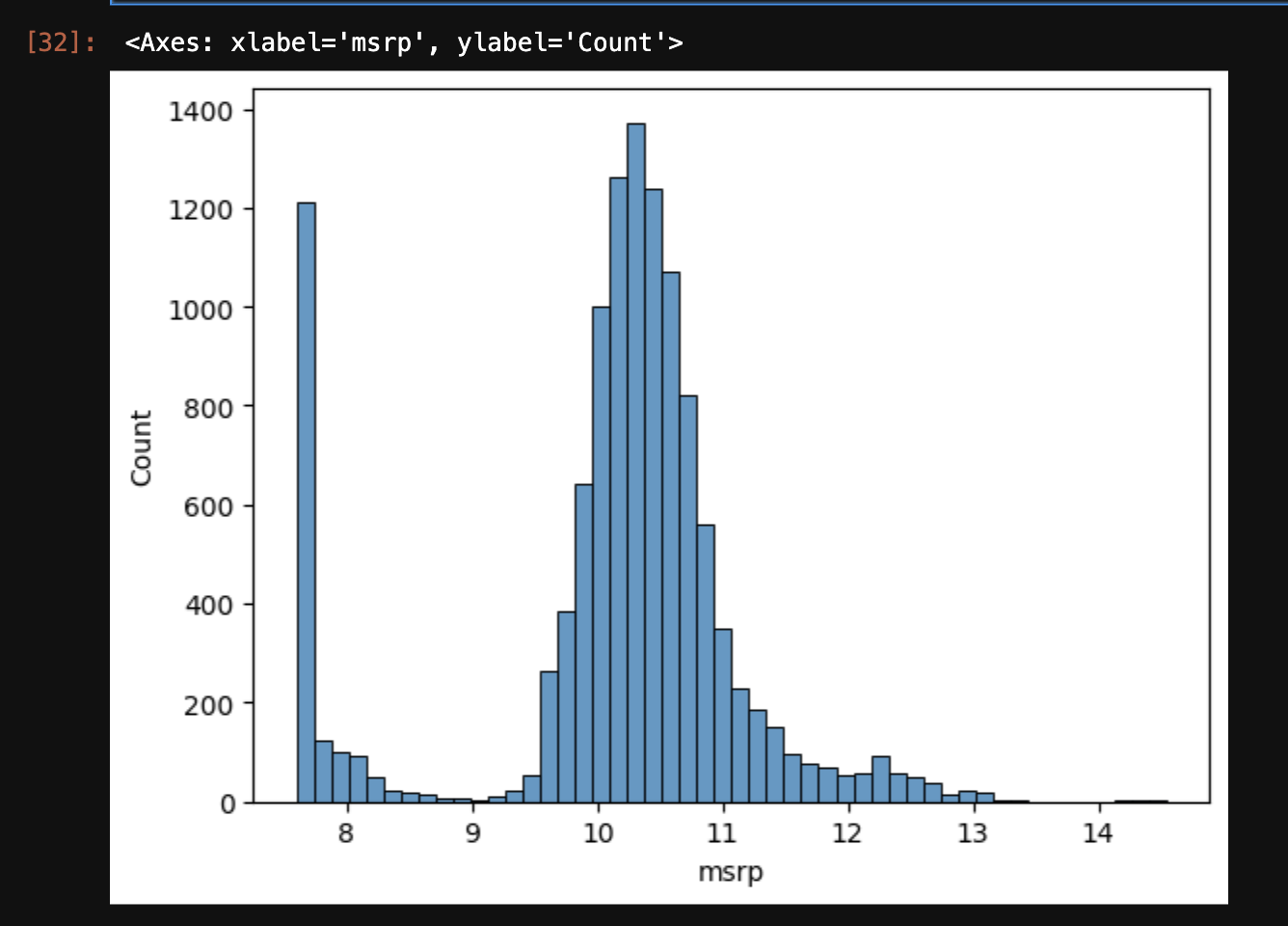

RuntimeWarning for dividing by 0. so, we can instead add 1 to all values, and then take a log. numpy has a built-in way of doing this by using log1p instead - np.log1p([0]) gives array([0.]) - the new histogram now looks as follows -

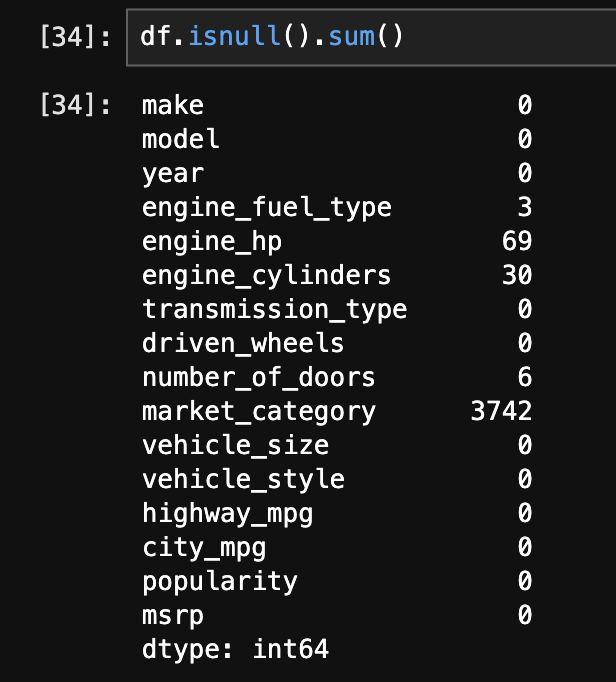

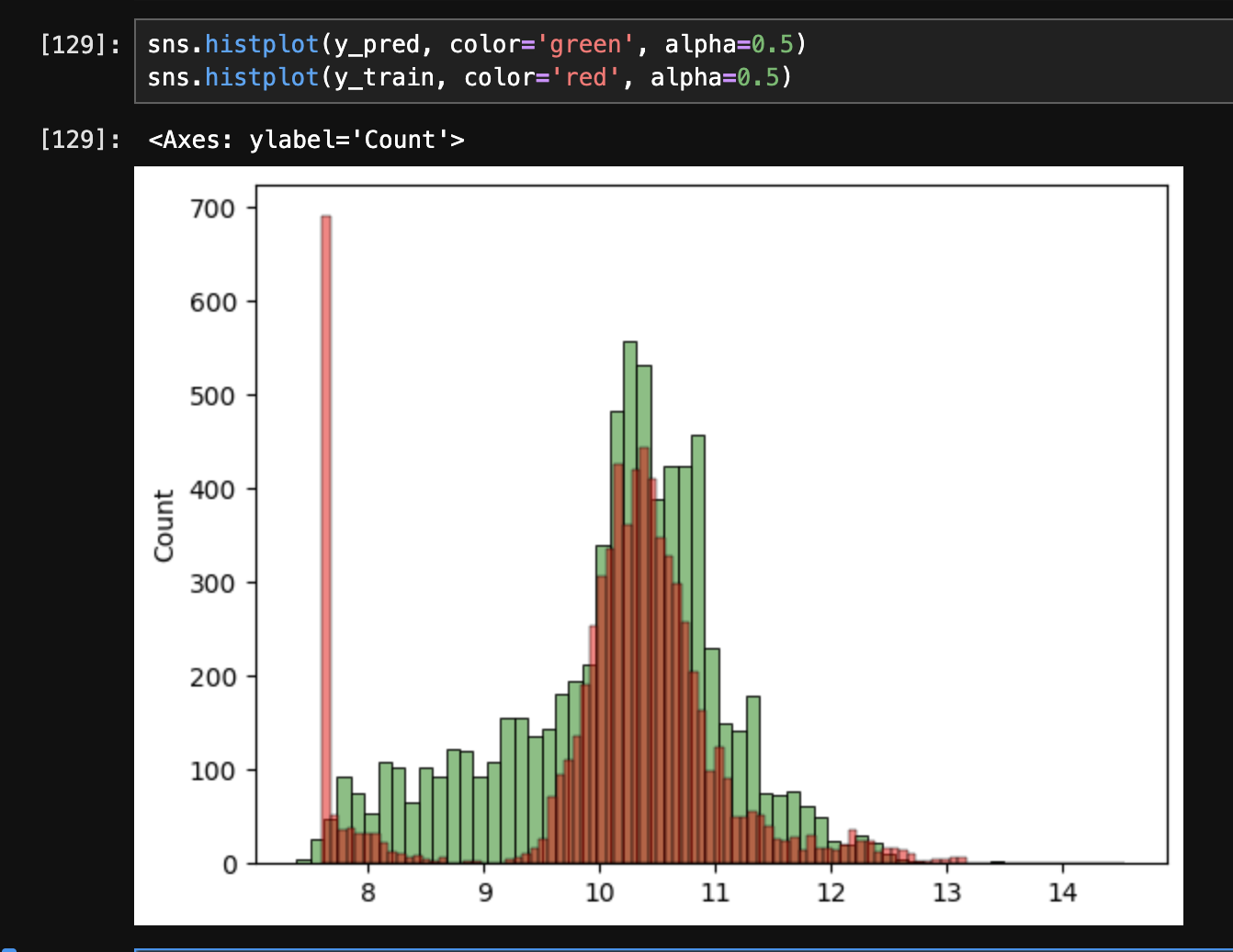

sns.histplot(np.log1p(df['msrp']), bins=50) - next, we get a sense of the missing values in the data using

df.isnull().sum() - now, we split the dataset into “training”, “validation”, and “test” sets. first, we determine their lengths -

import math

n = len(df)

n_test = math.floor(0.2 * n)

n_val = math.floor(0.2 * n)

n_train = n - (n_test + n_val)

n_train, n_test, n_val

- we observe that our dataset is grouped based on “make”, e.g. all cars with make bmw first and so on

- so, if we pick the elements from our dataset serially, e.g. validation first then training, our training data will not have any examples of cars with a make of bmw at all. so, we can instead, use for e.g. the technique below -

idx = np.arange(n)

np.random.shuffle(idx)

idx

# array([6236, 1578, 432, ..., 2381, 7640, 5545], shape=(11914,))

df_train = df.iloc[idx[ : n_train]]

df_test = df.iloc[idx[n_train : n_train + n_test]]

df_val = df.iloc[idx[n_train + n_test : ]]

- specify a seed for deterministic results -

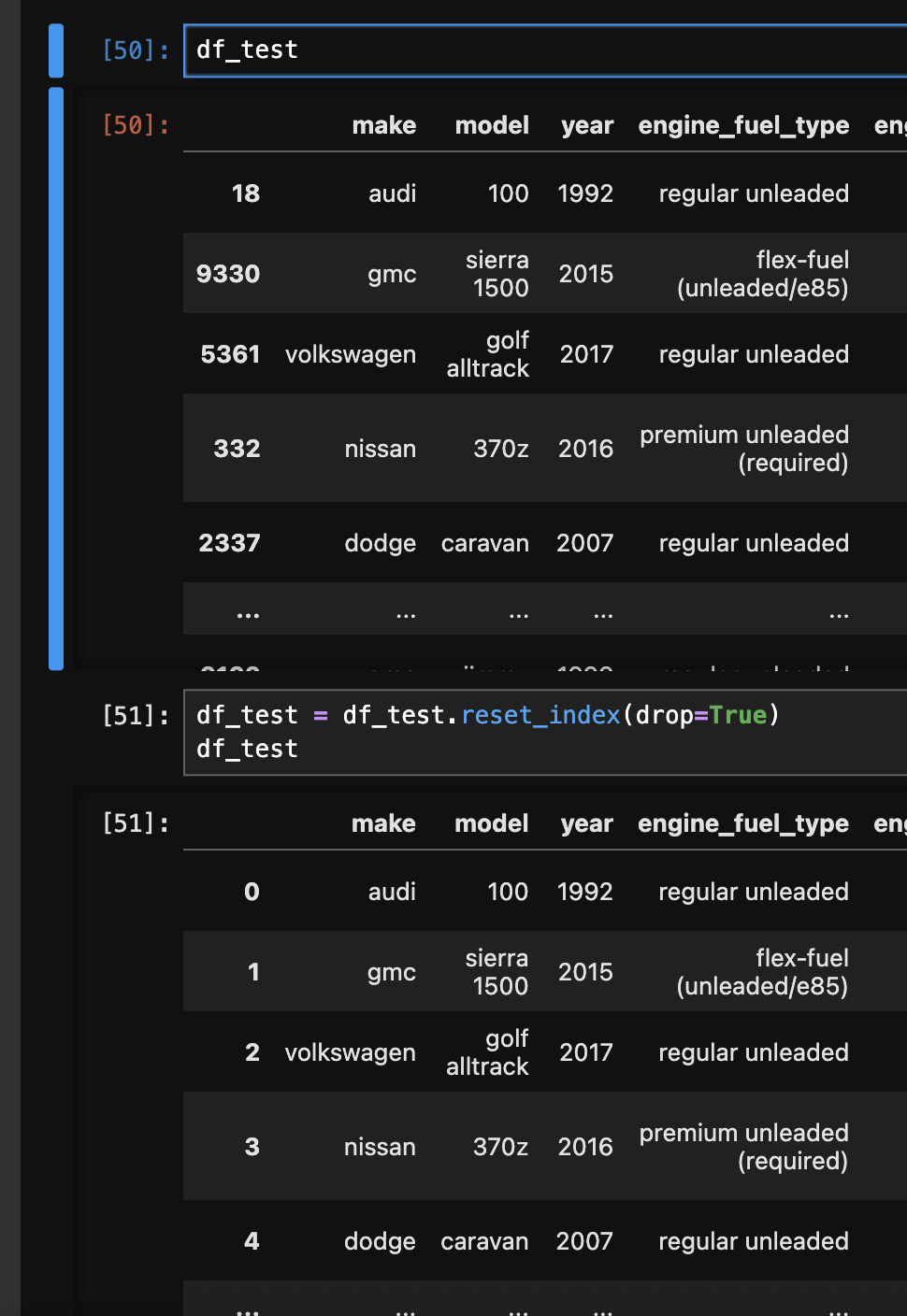

np.random.seed(2) - finally, the indices of all the datasets would be in random order (since we picked them in random order). so, we can reset the indices again using

df_test = df_test.reset_index(drop=True). refer the image below for the before and after - - next, we extract and separate the target variable vector from our feature matrix -

y_train = np.log1p(df_train['msrp'].array)

y_test = np.log1p(df_test['msrp'].array)

y_val = np.log1p(df_val['msrp'].array)

del df_train['msrp']

del df_test['msrp']

del df_val['msrp']

- the general formula for regression is like this - $g(x_i) = w_0 + x_{i1} \cdot w_1 + x_{i2} \cdot w_2 + … + x_{in} \cdot w_n$

- note - $w_0$ is called the “bias term”, which refers to the predictions if we have no information about the car

- this can be rewritten as $g(x_i) = w_0 + \sum_{j=1}^{n} x_{ij} \cdot w_j$

- assume that $x_{i0} = 1$, then we can rewrite it as $g(x_i) = \sum_{j=0}^{n} x_{ij} \cdot w_j$

- so, the idea would probably be to append a column of 1s to the list of features we receive

- we know that the summation portion is nothing but essentially a “vector vector multiplication”. so, we can rewrite it again as $g(x_i) = x_i^T \cdot w$

- this was for one record (the i in the formula denotes the ith record). when we consider for all the records / training data at once, it basically looks like this ($g(x) = x^T \cdot w$) -

\(\begin{pmatrix} 1 & x_{11} & x_{12} & \dots & x_{1n} \\ 1 & x_{21} & x_{22} & \dots & x_{2n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ 1 & x_{m1} & x_{m2} & \dots & x_{mn} \end{pmatrix} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} w_0 \\ w_1 \\ w_2 \\ \vdots \\ w_n \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} y_1 \\ y_2 \\ \vdots \\ y_m \end{pmatrix}\) - we need to calculate “weights” for the actual predictions. we cannot calculate the inverse of the feature matrix, because it is not a “square matrix”, it is (m * (n + 1))

- so, we construct a “gram matrix” to make it square. it is defined as $X^T \cdot X$

- finally after some basic math, $w$ can be calculated as $(X^T \cdot X)^{-1} \cdot X^T \cdot y$

- understand that this calculation would be an “approximation”. this is why the predictions and actual values do not align perfectly for the validation dataset as seen later

- some python code for calculating the weights -

def baseline_linear_regression(X, y):

ones = np.ones(X.shape[0])

X = np.column_stack([ones, X])

XTX = X.T.dot(X)

XTX_inv = np.linalg.inv(XTX)

w_full = XTX_inv.dot(X.T).dot(y)

w0 = w_full[0]

w = w_full[1:]

return w0, w

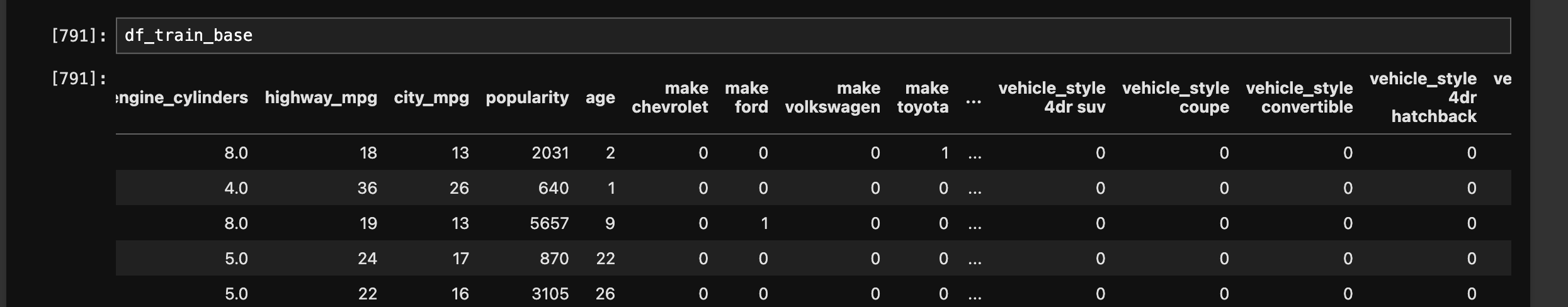

- now, we extract just the numeric features from the dataframe, since linear regression can only be applied to numerical features -

numeric_cols = df_train.dtypes[df.dtypes != 'object'].index

df_train_base = df_train[numeric_cols]

- next, we need to deal with missing values as otherwise, the matrix and vector multiplication will fail. filling with 0 is like for e.g. “ignoring” a feature. sometimes, it might not make sense. e.g. an engine with missing horsepower might not work, so we might want to fill it with the mean value instead

df_train_base = df_train_base.fillna(0)

- next, we calculate the weights -

w0, w = baseline_linear_regression(df_train_base, y_train) - finally, we make the predictions on the validation dataset as follows. note how we first need to perform the same transformations to the validation feature matrix that we did to the training feature matrix -

df_val_base = df_val[numeric_cols]

df_val_base = df_val_base.fillna(0)

y_pred = w0 + df_val_base.dot(w)

- we can compare our predictions with the actual values as follows -

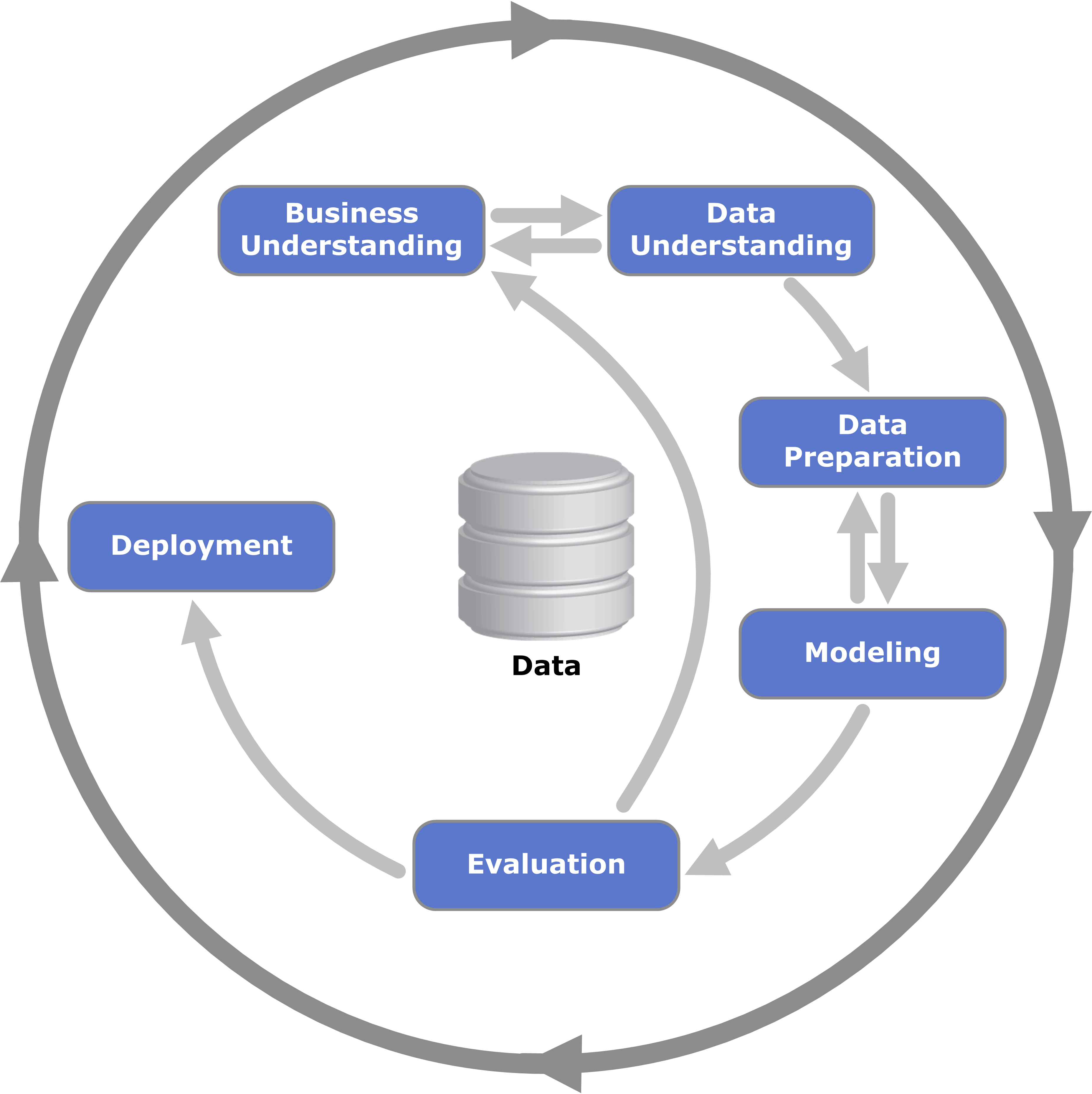

- we can evaluate regression models using “rmse” or “root mean square error”. it helps measure the error associated with the model being evaluated. it is the “metric” we discussed in crisp dm it can be used to compare the different models, and then choose the best one. the formula is as follows \(\text{RMSE} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} (g(x_i) - y_i)^2}\)

- here, $g(x_i)$ is the “prediction”, $y_i$ is the “actual value”, and $m$ is the number of records. we can implement it using python as follows -

def rmse(y_pred, y):

e = y_pred - y

se = e ** 2

mse = se.mean()

return math.sqrt(mse)

rmse(y_pred, y_val)

# 0.5146325131050283

- “feature engineering” is the process of creating new features. e.g. we change the year feature to “age” instead

- we create a “prepare x” function, so that the different feature matrices like training and validation can simply be passed to it. also notice how we create a copy at the beginning to avoid changing the original dataframe

def prepare_features(X):

numeric_cols = X.dtypes[X.dtypes != 'object'].index

X = X[numeric_cols].copy()

X['age'] = X['year'].max() - X['year']

del X['year']

X = X.fillna(0)

return X

- we see that rmse drops down to 0.49 from 0.51 when we do this

- “categorical variables” - typically strings, e.g. make, model, etc. however, some like number of doors are categorical but numbers

- we can do analysis on features like this as follows -

df_train['number_of_doors'].value_counts() - “one-hot encoding” - we have a binary column for each category value. e.g. the number of doors column is split into - is number of doors 2, is number of doors 3 and so on. each of these hold a 1 or 0, depending on the value that the record has for the number of doors column -

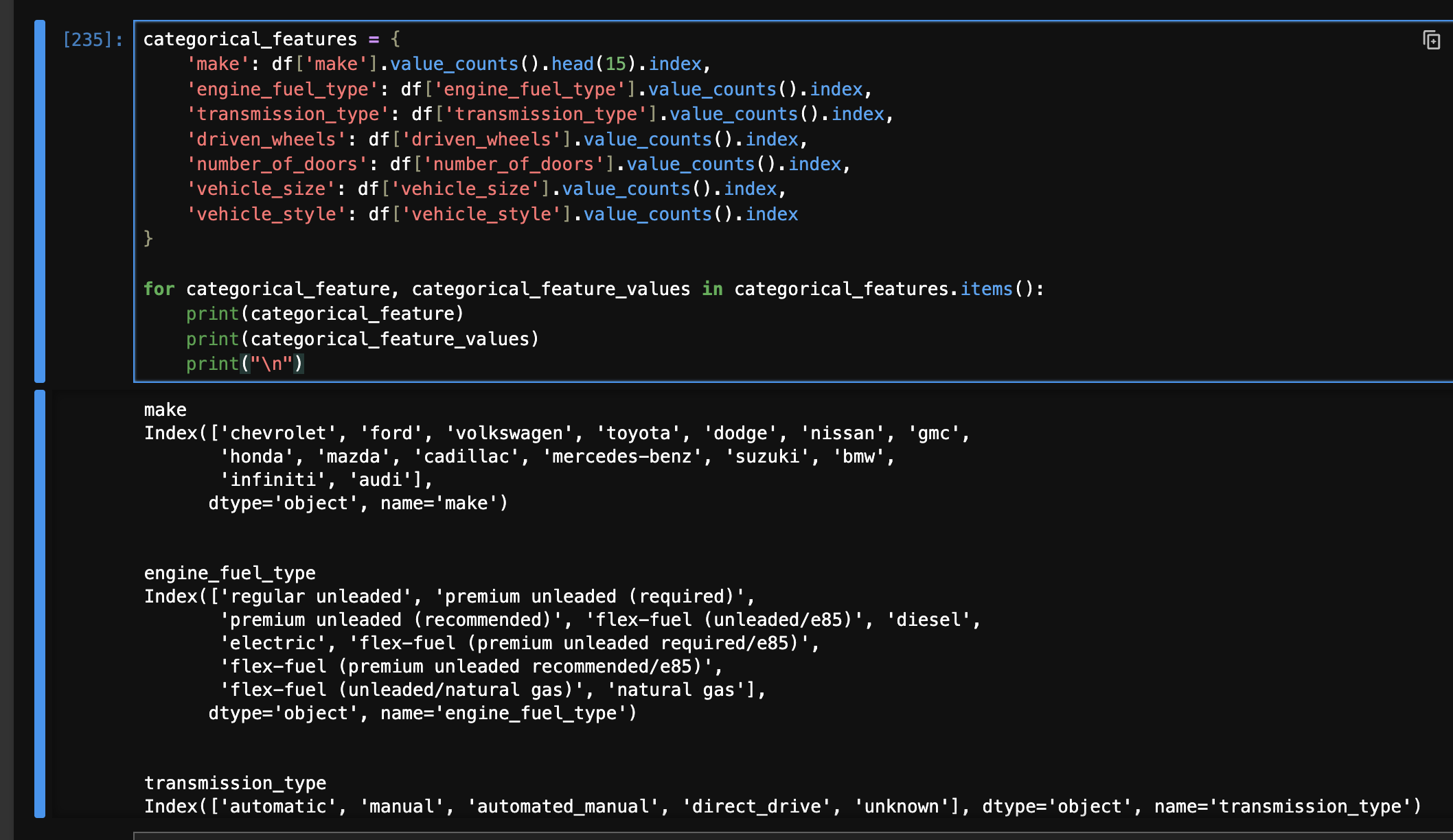

\(\begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ 3 \\ 4 \\ 2 \\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ \end{pmatrix}\) - as “make” has a lot of unique values, we only take the top 15 values. i guess the unpopular cars with none of the makes would hold a 0 for all the make related categorical columns

- now, we first construct a dictionary as follows -

categorical_features = {

'make': df['make'].value_counts().head(15).index,

'engine_fuel_type': df['engine_fuel_type'].value_counts().index,

'transmission_type': df['transmission_type'].value_counts().index,

'driven_wheels': df['driven_wheels'].value_counts().index,

'number_of_doors': df['number_of_doors'].value_counts().index,

'vehicle_size': df['vehicle_size'].value_counts().index,

'vehicle_style': df['vehicle_style'].value_counts().index

}

- we add this snippet to our prepare_features function -

for feat, vals in categorical_features.items():

for val in vals:

X[f'{feat} {val}'] = (X[feat] == val).astype(int)

del X[feat]

- the matrix now looks like this -

- however, now when we try predicting, we see the following problems -

- we notice that the rmse is now 1391

- sometimes on rerunning the entire notebook, i see the error that “the matrix is singular”

- w0 / bias shows a very huge value - np.float64(-4129369813575166.5)

- even some of the weights in our vector w are very huge

- this happens because the inverse of our “gram matrix” might not exist. we have a lot of features in binary form after we introduced the categorical features. because of this, some of them might become duplicate or basically, some column can be expressed as a linear combination of other columns. when this happens, the inverse of the matrix does not exist. we get the error that “the matrix is singular”. this can be demonstrated using a quick example below, where the second and third columns are identical -

x = np.array([

[1, 2, 2],

[3, 4, 4],

[5, 1, 1]

])

np.linalg.inv(x.T.dot(x))

# LinAlgError: Singular matrix

- the solution is “regularization”. we add a certain number on the diagonal. this ensures that the columns have different values, and thus can be inverted. this can be done quickly using the identity matrix. the larger the value we add i.e. the larger the multiplier (0.01 below), the more “in control” the weights would be. we can make the following modification to

baseline_linear_regression (add the second line) -XTX = X.T.dot(X)

XTX = XTX + (0.01 * np.eye(XTX.shape[0]))

XTX_inv = np.linalg.inv(XTX)

- note - the regularization technique of adding a value on the diagonal is called “ridge regression”

- after this, we see that the rmse becomes 0.44

- the regularization value we added i.e. 0.01 is a “hyperparameter”

- tuning the model means finding the best possible value of this hyperparameter. so, we change

baseline_linear_regression to accept it as a parameter instead, and iterate through its different possible values of the regularization as follows - - one common technique is that after finding the best model, hyper parameters, etc, we again train it but using both the training and validation data together. then, we test it against the testing data -

df_full = pd.concat([df_train, df_test])

df_full.reset_index(drop=True)

y_full = np.concat([y_train, y_val])

df_full_prepared = prepare_features(df_full)

df_test_prepared = prepare_features(df_test)

w0, w = baseline_linear_regression(df_full_prepared, y_full, r)

y_pred = w0 + df_test_prepared.dot(w)

rmse(y_pred, y_test)

- finally, recall that the target variable is using log1p, so to get the final price, we use

np.expm1

- example - the company determines and sends out discounts and promotions to customers to avoid churning

- $g(x_i) = y_i$. we use “binary classification” for the $i$th customer

- $y_i$ is the model’s prediction and belongs to {0,1}, where 0 indicates the customer is not likely to churn and 1 indicates the customer is likely to churn

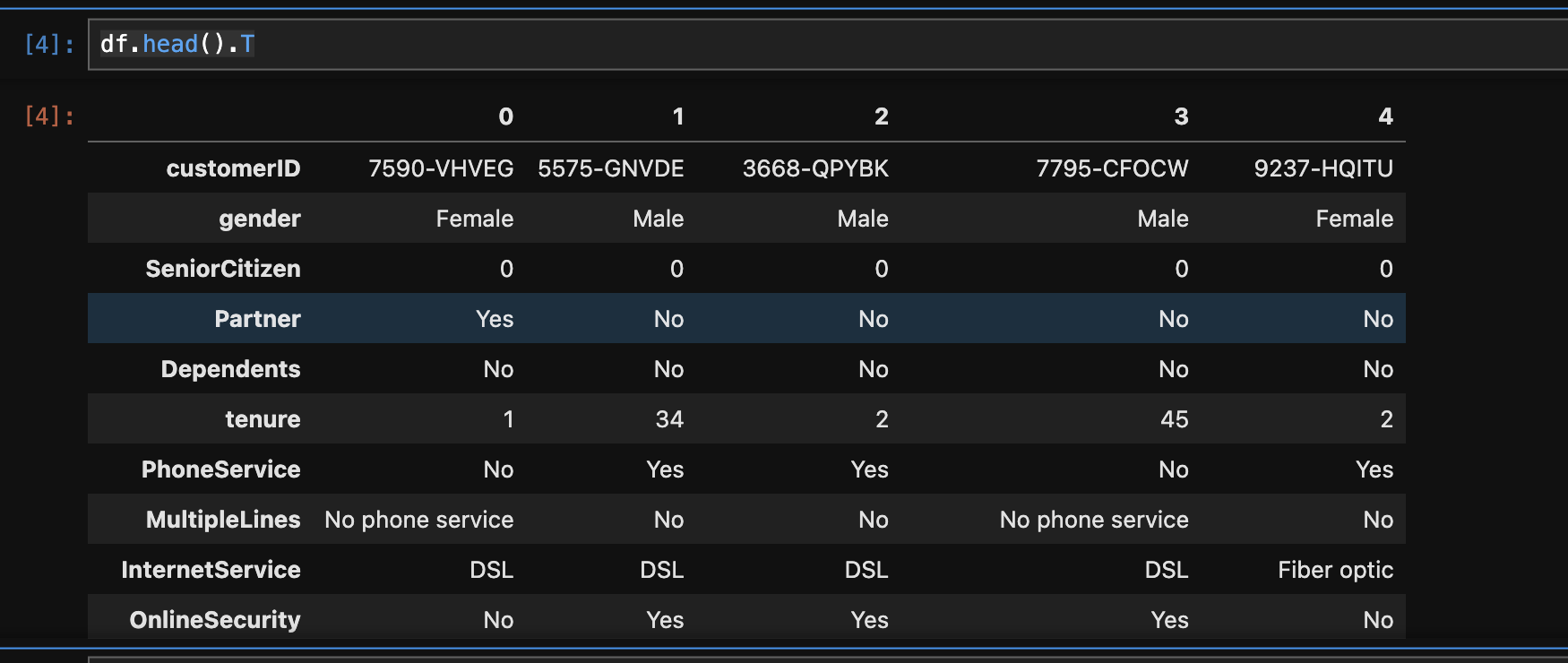

- one useful trick to analyze pandas dataframes with lot of columns -

df.head().T - data cleanup example for a numerical column -

- when we run

df.types, we see totalcharges of type object - when we try running

pd.to_numeric(df.totalcharges), we get the following error - ValueError: Unable to parse string " " - by some analysis, we can see that there are 11 records with totalcharges as a space

- so, use

pd.to_numeric(df.totalcharges, errors='coerce') instead to sets nan for such records

- so, our final transformation looks as follows -

df['totalcharges'] = pd.to_numeric(df['totalcharges'], errors='coerce')

df['totalcharges'] = df['totalcharges'].fillna(0)

- convert yes / no to integers -

df['churn'] = (df['churn'] == 'yes').astype(int) - finally, we run checks for null values using

df.isnull().sum() - recall our definition of $y_i$ i.e. churn earlier. so, to get the churn rate of our company, we can calculate the mean of the churn column now -

df['churn'].mean() - we will use sckit learn in this section, and not core apis of pandas and numpy directly

- splitting the dataset - note how we grab 25% of the full train dataframe so that we have the split of 60-20-20 -

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

full_train_df, test_df = train_test_split(df, test_size=0.2, random_state=1)

train_df, val_df = train_test_split(full_train_df, test_size=0.25, random_state=1)

full_train_df = full_train_df.reset_index(drop=True)

train_df = train_df.reset_index(drop=True)

val_df = val_df.reset_index(drop=True)

test_df = test_df.reset_index(drop=True)

full_train_y = full_train_df['churn'].values

train_y = train_df['churn'].values

val_y = val_df['churn'].values

test_y = test_df['churn'].values

del full_train_df['churn']

del train_df['churn']

del val_df['churn']

del test_df['churn']

- now, we try to look at the churns for different “groups”, and compare it to the “global churn” -

df['churn'].mean()

# np.float64(0.2653698707936959)

df.groupby('gender')['churn'].mean()

# gender

# female 0.269209

# male 0.261603

df.groupby('partner')['churn'].mean()

# partner

# no 0.329580

# yes 0.196649

- next, we define our numerical and categorical columns -

numerical_columns = ['monthlycharges', 'tenure', 'totalcharges']

categorical_columns = ['contract', 'dependents', 'deviceprotection', ... , 'techsupport']

- and we ensure we only use them for our analysis. we do not want to have columns like “customer id”, which are not relevant features for our analysis -

full_train_df = full_train_df[categorical_columns + numerical_columns]

train_df = train_df[categorical_columns + numerical_columns]

val_df = val_df[categorical_columns + numerical_columns]

test_df = test_df[categorical_columns + numerical_columns]

- observe the unique values per category -

df[categorical_columns].nunique()contract 3

dependents 2

deviceprotection 3

gender 2

...

- intuition - it tells us that the gender does not play a significant role in churn, while having a partner does

- technique 1 - “churn rates” - calculated as (churn of a group) - (global churn rate). if it is > 0, it means that the group is at a higher risk of churning. however, as we saw above, the “magnitude” matters as well i.e. customers having no partners are at a much higher risk of churning than the customer being a female

- technique 2 - “risk ratios” - calculated as (churn rate of group) / (global churn rate). a risk ratio > 1 indicates a higher risk of churning, while a risk ratio < 1 indicates a lower risk

- so, we can perform some “exploratory data analysis” for all the categorical variables as follows -

from IPython.display import display

for categorical_column in categorical_columns:

display(df.groupby(categorical_column)['churn'].mean())

print()

- “mutual information” - a concept from “information theory”, that tells us how much we can learn about one random variable, if we know about another random variable

- example how much do we learn about “churn”, if we know about a certain feature, e.g. type of contract - “month-to-month” vs “one year” vs “two year”

- sckit learn already implements this for us, and we can use it as follows. note - the order of columns does not matter. it clearly shows how gender does not matter unlike type of contract -

from sklearn.metrics import mutual_info_score

mutual_info_score(df['churn'], df['contract']) # 0.09845305342598942

mutual_info_score(df['churn'], df['gender']) # 3.7082914405128786e-05

- note - “mutual information” is applicable for “categorical variables” only

- so, we can use

df.apply to get the mutual information score for all the columns. apply accepts a function that gets called for every column of the dataframe. we also sort it in decreasing order to quickly analyze which columns are important -df[categorical_columns].apply(lambda series: mutual_info_score(series, df['churn'])).sort_values(ascending=False)

# contract 0.098453

# onlinesecurity 0.064677

# techsupport 0.063021

# ...

- for numerical variables, we use “correlation”. also called “pearson’s correlation”

- it is denoted by $r$, and $r \in [-1, 1]$

- negative correlation indicates that as for e.g. value of one variable increases, the other variable tends to decrease and vice versa

- the higher the magnitude, the more they are correlated - upto 0.2 is “low correlation”, 0.2 - 0.5 is “moderate correlation” and otherwise it is “strong correlation”

- look at the correlation of numerical features -

df[numerical_columns].corrwith(df['churn']) - here, we see a negative correlation with tenure - which basically means the longer a person stays with the company, the lesser is the churn rate. we can further perform analysis as follows, e.g. compare the churn rate for people who have stayed less than vs more than a year

df[df['tenure'] <= 12]['churn'].mean() # np.float64(0.47438243366880145)

df[df['tenure'] > 12]['churn'].mean() # np.float64(0.17129915585752523)

- this time, we perform one hot encoding using scikit learn -

from sklearn.feature_extraction import DictVectorizer

- since we are using “dict vectorizer”, we use

.to_dict(orient='records') to convert the dataframe to a list of dictionariestrain_dicts = train_df.to_dict(orient='records')

# [

# {'customerid': '8015-ihcgw', 'gender': 'female', ... 'totalcharges': 8425.15},

# {'customerid': '1960-uycnn', 'gender': 'male', .. 'streamingmovies': 'no'},

# ...

- we need to kind of “train” the vectorizer on some sample data. using that sample data, the vectorizer determines the different categories and their values, and accoridngly decide on the columns etc. note - we might end up having a lot of zeroes, and scikit learn would use compressed sparse matrices for efficiency etc. however, we set sparse as false here to have the original one hot encoding behavior of 0 / 1 for each value of the category as we saw in regression

dv = DictVectorizer(sparse=False)

dv.fit(train_dicts)

- note how we specified passed in all columns i.e. numerical and categorical to the fit. it is intelligent enough to leavre the numerical columns untouched, e.g. senior citizen and total charges would become - [senior citizen=0, senior citizen=1, total charges]

- why is this important - because remmeber, while we do not encode the numerical columns in this step, they still have weights in our actual prediction (how logistic regression works is discussed later)

- finally, we obtain the matrices with the encoding using

transformtrain_mat = dv.transform(train_dicts)

# array([[0.00000e+00, 1.00000e+00, 0.00000e+00, ..., 1.00000e+00,

# 4.10000e+01, 3.32075e+03],

# [0.00000e+00, 0.00000e+00, 1.00000e+00, ..., 0.00000e+00,

# 6.60000e+01, 6.47185e+03],

- note how it is no longer a dataframe, but a 2d numpy array i guess? we can obtain the corresponding feature names for the 2d array as follows -

dv.get_feature_names_out()

# array(['contract=month-to-month', 'contract=one year', 'contract=two year',

# 'dependents=no', 'dependents=yes',

- so, the final code snippet is as follows -

dv = DictVectorizer(sparse=False)

train_dicts = train_df.to_dict(orient='records')

val_dicts = val_df.to_dict(orient='records')

dv.fit(train_dicts)

train_mat = dv.transform(train_dicts)

val_mat = dv.transform(val_dicts)

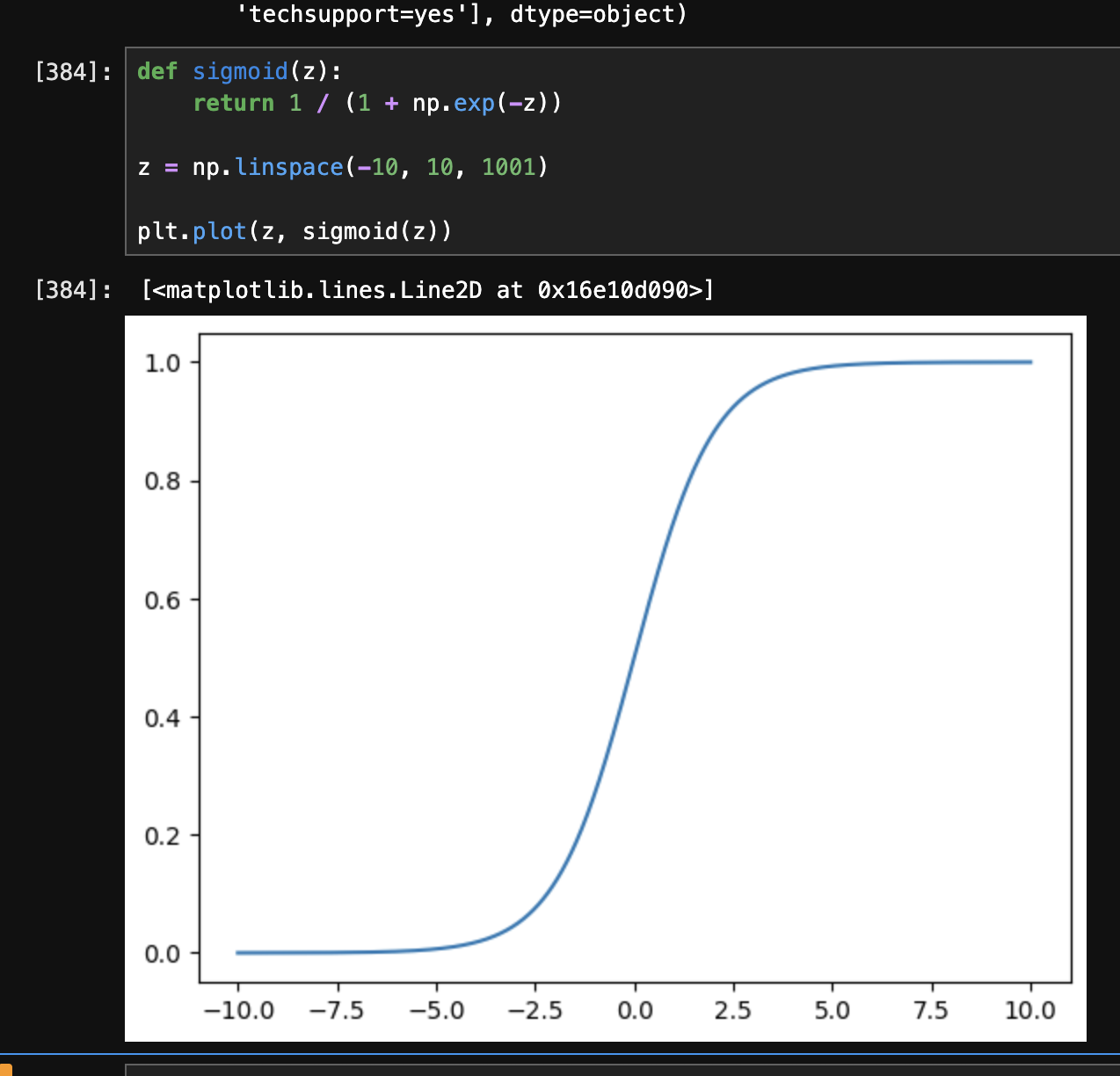

- recall how in our case, $x \in [-\infty, \infty]$ (i.e. x can be any real number, e.g. tenure), while $y \in {0, 1}$ (i.e. y can only be 0 or 1 i.e. the churn). in case of “logistic regression”, we apply the “sigmoid” function to the “linear regression” formula. the linear regression formula can give us any value from $-\infty$ to $+\infty$, while the sigmoid function converts the output to be between 0 and 1, thus helping us with “binary classification”. at $-\infty$, its output is 0 and at $+\infty$, its output is 1. at 0, its output is 0.5

- formula of sigmoid - $\sigma(z) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-z}}$

- we can look at its graph as follows -

- so, we can use the logistic regression model as follows -

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

model = LogisticRegression()

model.fit(train_mat, train_y)

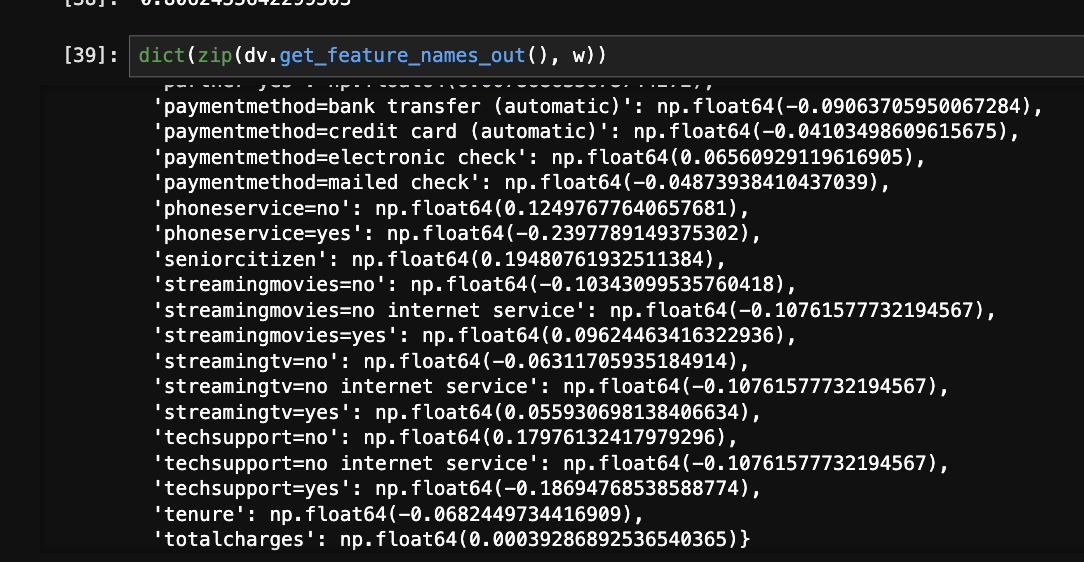

- we can obtain the weights from the model like this

w = model.coef_[0]

w0 = model.intercept_[0]

- understand what the weights are - they are the coefficients for all the features we have. e.g. look at the below image on how we can easily look at the correlation of each feature with the target variable. also, notice how numerical columns like total charges were considered automatically, as the dict vectorizer did not touch them -

- we can use the model as follows. the first one is called “hard predictions”, as it would have the exact label of 0 or 1 (churn or not churn). the second one is called “soft predictions”, as it would give the probabilities instead. note how in case of soft predictions, we see two elements per record as the first one is probability of 0 (not churn), and second is probability of 1 (churn)

model.predict(val_mat) # array([0, 0, 0, ..., 0, 1, 1], shape=(1409,))

model.predict_proba(val_mat) # array([[0.98157471, 0.01842529], ..., [0.30467382, 0.69532618]], shape=(1409, 2))

- recall that we used rmse in regression to measure the accuracy of our model. in this case we use a method called “accuracy” as follows i.e. average number of times our predictions were correct -

val_y_predict = model.predict(val_mat)

(val_y_predict == val_y).astype('int').mean()

- we can also use scikit learn for the same -

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

accuracy_score(val_y, model.predict(val_mat))

- finally, we do it for the training and validation dataset together, and predict it against the test dataset -

full_train_dicts = full_train_df.to_dict(orient='records')

test_dicts = test_df.to_dict(orient='records')

dv = DictVectorizer(sparse=False)

dv.fit(full_train_dicts)

full_train_mat = dv.transform(full_train_dicts)

test_mat = dv.transform(test_dicts)

model = LogisticRegression()

model.fit(full_train_mat, full_train_y)

pred_y = model.predict(test_mat)

accuracy_score(test_y, pred_y)

- “accuracy” as we saw in classification is the number of correct predictions / total number of predictions

- how the prediction was working - we used regression that spit out a real number, which was then passed via the sigmoid function to clamp it between 0 and 1. finally we used a threshold of 0.5 to label it as 0 or 1 i.e. below 0.5 is 0 (not churn) and above 0.5 is 1 (churn). this 0.5 is called the “decision threshold”. below is a python code breakdown. recall how

predict_proba works from classification i.e. using soft predictions. so, we only select its second column i.e. the probability of churn, and then look at all its values where it is >= 0.5pred_y_proba = model.predict_proba(test_mat)[:,1]

accuracy_score(test_y, pred_y_proba >= 0.5)

- my understanding - the decision threshold is therefore like a hyperparameter, which we can test as follows, and we see that accuracy is a little higher at for e.g. 0.6 -

- using decision threshold of 1 basically means we say no customers are going to churn. however, we can see that even this dummy model has accuracy of 75%, while our decision threshold of 0.5 has 81% accuracy

- this is happening because the data is “unbalanced”. this is called “class imbalance”, as we have more instances of 1 category than the other. 75% of the testing dataset contains of people who are non churning -

(test_y == 1).sum(), (test_y == 0).sum()

# (np.int64(348), np.int64(1061))

- so, instead of using “accuracy”, we use “confusion table”

- we have four scenarios. true means our prediction was correct, positive means that our prediction belongs to the “positive class” / 1 / customer actually churned

- “true positive” - we predicted churn, customer churned. $g(x_i) >= t$, $y_i = 1$

- “true negative” - we predicted no churn, customer did not churn. $g(x_i) < t$, $y_i = 0$

- “false positive” - we predicted churn, customer did not churn. $g(x_i) >= t$, $y_i = 0$

- “false negative” - we predicted no churn, customer churned. $g(x_i) < t$, $y_i = 1$

- we can write it in python code as follows -

actual_positive = (test_y == 1)

actual_negative = (test_y == 0)

t = 0.5

predict_positive = (pred_y_proba >= t)

predict_negative = (pred_y_proba < t)

tp = (predict_positive & actual_positive).sum()

tn = (predict_negative & actual_negative).sum()

fp = (predict_positive & actual_negative).sum()

fn = (predict_negative & actual_positive).sum()

tp, tn, fp, fn

# (np.int64(204), np.int64(943), np.int64(118), np.int64(144))

- this “confusion matrix” is usually represented in the following manner. we then “normalize” it / see the percentages of each type -

confusion_matrix = np.array([

[tn, fp],

[fn, tp]

])

confusion_matrix / confusion_matrix.sum()

# array([[943, 118], [144, 204]])

# array([[0.66926899, 0.08374734], [0.10220014, 0.14478353]])

- based on the confusion matrix, we can also see that “accuracy” was basically (tp + tn) / (tp + tn + fp + fn)

- “precision” - fraction of correct positive predictions. it can be calculated as (tp / (tp + fp)). e.g. in our case, it would mean that we would send the promotional email to an extra 33% of people who should not have gotten the email, thus leading to potential losses

p = tp / (tp + fp)

p # np.float64(0.6335403726708074)

- “recall” - fraction of actual positives that were correctly predicted. it can be calculated as (tp / (tp + fn)). e.g. in our case, it would mean that we would correctly send the email to only 58% of the customers who would actually churn, thus missing out on the remaining customers

r = tp / (tp + fn)

r # np.float64(0.5862068965517241)

- so, while the accuracy was high, precision and recall are not. hence, accuracy can be misleading in case of for e.g. “class imbalance”

- now, we will explore “roc curves” i.e. “receiver operating characteristics”

- it is a method of evaluating the performance of a binary classification model across many “thresholds” at once

- we are interested in two values fpr and tpr

- “fpr” or “false positive rate” = (fp / (fp + tn)) - basically, 1st row of confusion matrix i.e. where target variable is 0

- “tpr” or “true positive rate” = (tp / (tp + fn)) - basically, 2nd row of confusion matrix i.e. where target variable is 1

- note - looks like tpr and recall have the same formula?

- the goal is to minimize false positive rate / maximize true positive rate

- roc curves looks at multiple thresholds at once

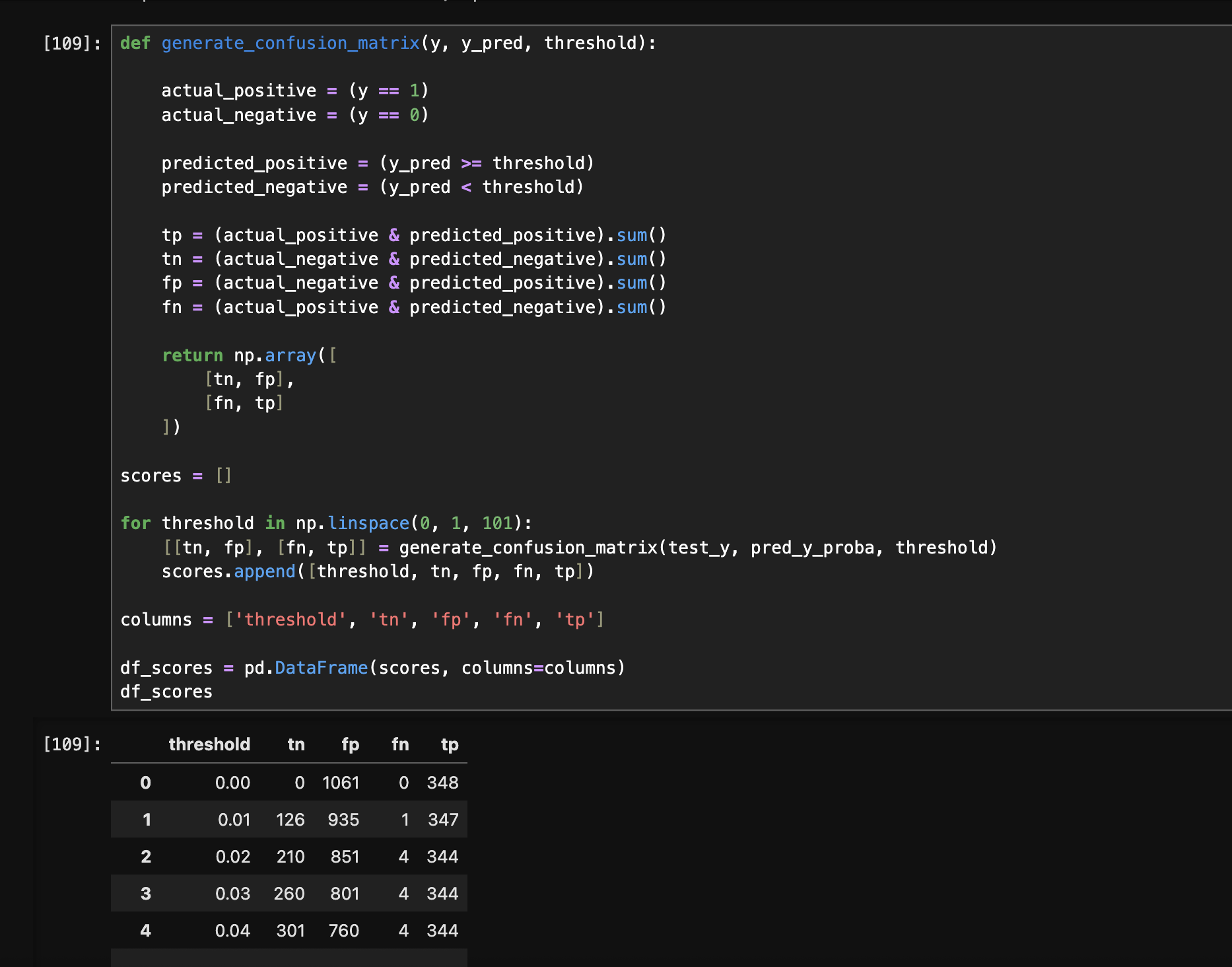

- first, we generate the following dataframe for the different thresholds and their respective values for the confusion matrix -

- next, we compute the remaining columns as follows -

df_scores['precision'] = df['tp'] / (df['tp'] + df['fp'])

df_scores['recall'] = df['tp'] / (df['tp'] + df['fn'])

df_scores['fpr'] = df['fp'] / (df['fp'] + df['tn'])

df_scores['tpr'] = df['tp'] / (df['tp'] + df['fn'])

df_scores

- note - whatever we did manually till now, can be done automatically using scikit learn as follows. we just pass it the actual y and probabilities, and it returns us all three - fpr, tpr and thresholds -

from sklearn.metrics import roc_curve

fpr, tpr, thresholds = roc_curve(test_y, pred_y_proba)

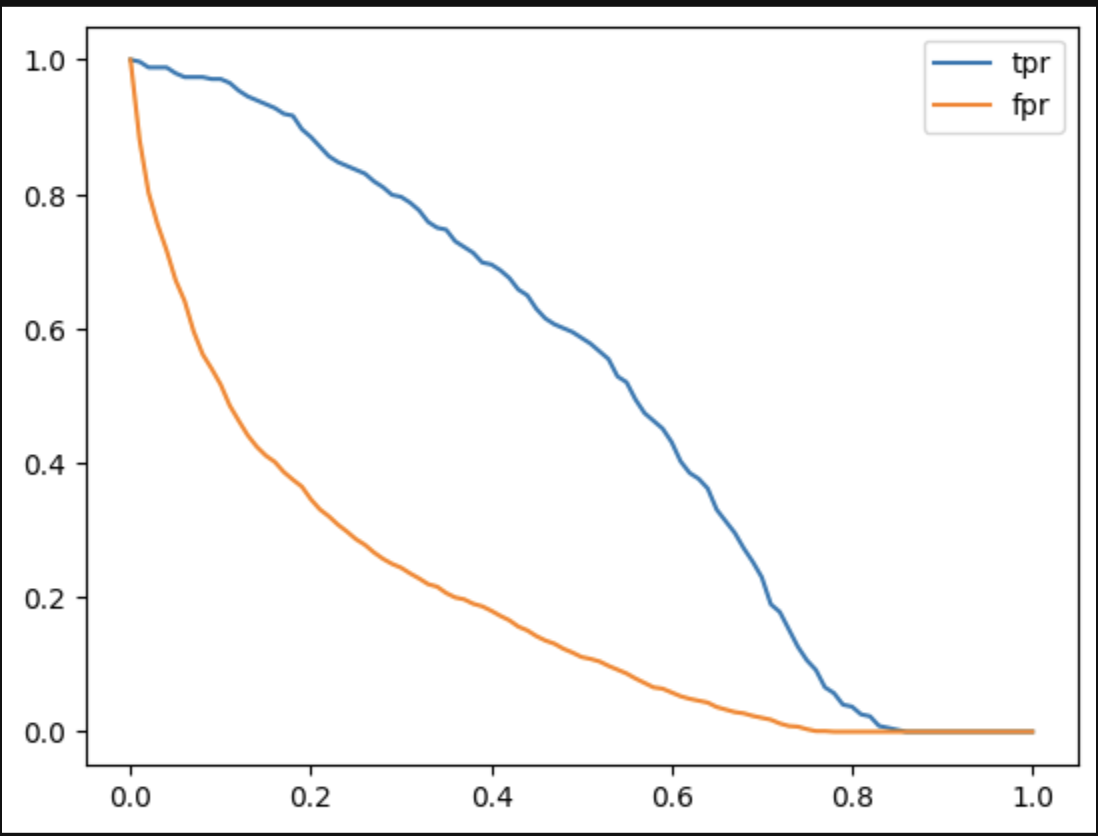

- next, we can plot the roc curves as follows -

plt.plot(df_scores['threshold'], df_scores['tpr'], label='tpr')

plt.plot(df_scores['threshold'], df_scores['fpr'], label='fpr')

plt.legend()

- we want fpr to be towards 0, and tpr to be towards 1

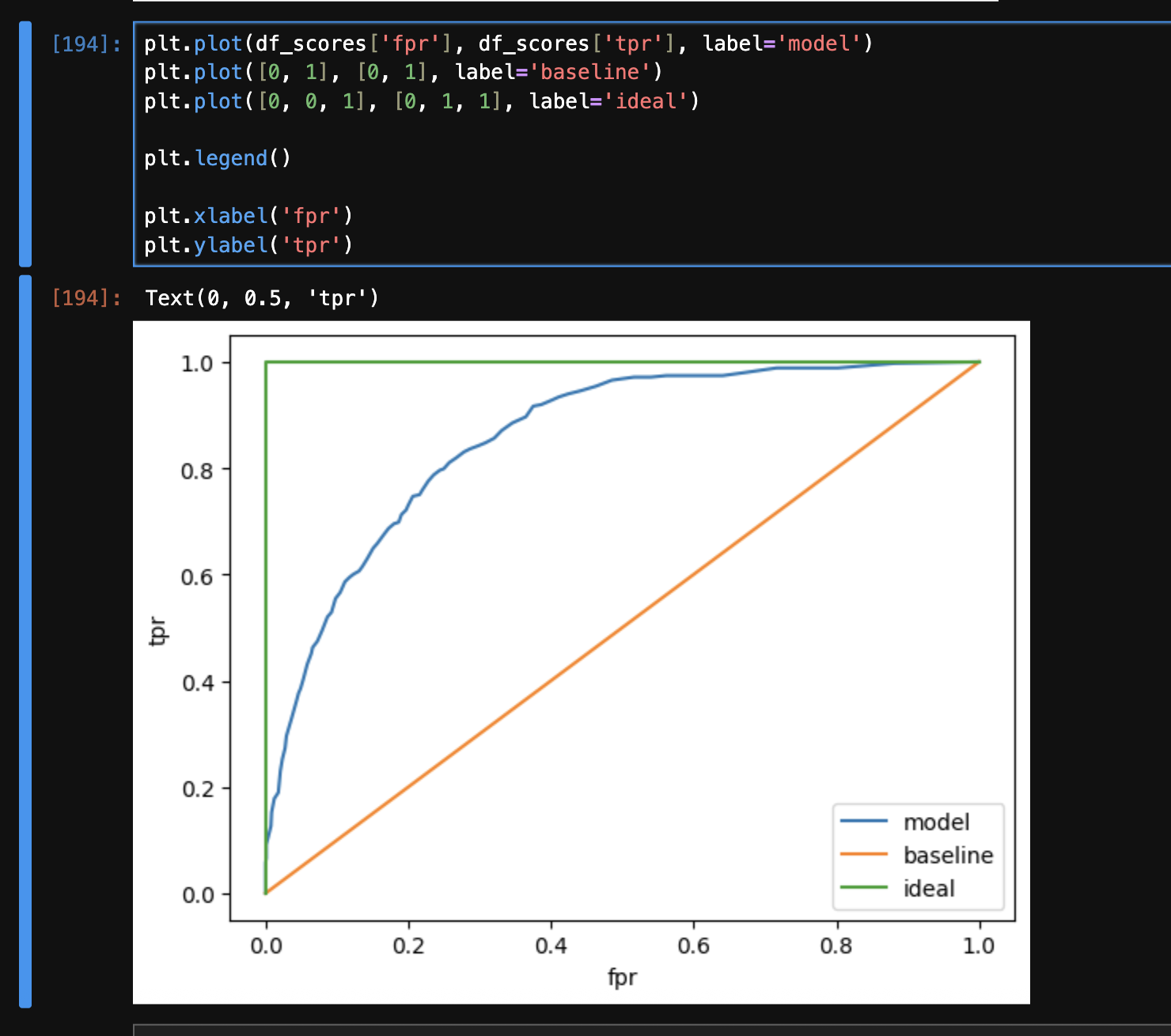

- now, we now plot tpr and fpr against each other. we plot the following three graphs

- note - below is intuition, there may be more math to it

- at the beginning of the curves, threshold is basically 0. so, our model does not predict anything as positive. so, fpr and tpr are both typically 0

- at the end of the curves, our threshold is 1. so, our model does not predict anything as negative. hence, we have both tpr and fpr as 1

- first, we add a baseline. the idea is usually that a models should never go below the baseline. the line for this is a straight line. this means as our tpr increases (which is good), our fpr increases as well (which is bad)

plt.plot([0, 1], [0, 1], label='baseline')

- then, we also plot our model’s tpr and fpr

- finally, we plot our “north star” / ideal state, which is basically tpr = 1 and fpr = 0. to complete the curve, we add the two additional points for thresholds 0 and 1

plt.plot([0, 0, 1], [0, 1, 1], label='ideal')

- “area under roc curve” is a useful metric of calculating the performance of a binary classification model

- for the ideal model, the area under the roc curve is 1, while for the baseline model, the area under the curve is 0.5. so, the area under roc curve for our model should be somewhere between 0.5 and 1

- scikit learn has a function called “auc” to calculate the area under any curve. we can use it as follows (recall that fpr and tpr were already calculated using

roc_curve) -from sklearn.metrics import auc

print(auc(fpr, tpr)) # model - 0.8569948649614871

print(auc([0, 0, 1], [0, 1, 1])) # ideal - 1.0

print(auc([0, 1], [0, 1])) # baseline - 0.5

- intrerpretation of area under roc curve - the probability that a randomly selected positive instance is ranked higher than a randomly selected negative instance. ranked higher is basically means higher probability. instance basically means actual labels / test y. this happens because assume we predict probability as 0.3. say our threshold is 0.5, we classify it as not churning, but it might actually be a positive instance i.e. a churned customer. so, area under roc curve basically tells us the probability that a randomly selected churning customer actually has higher probability as per our model than a randomly selected non churning customer. see how we can write the following python code to get the same result as the auc above -

import random

trials = 1000000

neg_instances = pred_y_proba[test_y == 0]

pos_instances = pred_y_proba[test_y == 1]

success_count = 0

for i in range(trials):

probab_neg = random.choice(neg_instances)

probab_pos = random.choice(pos_instances)

success_count += (probab_pos > probab_neg)

success_count / trials # np.float64(0.857021)

- we build a credit risk scoring model, that predicts whether a bank should lend money to a client or not

- we analyze historical data of customers who defaulted, given the details like the amount they borrowed, their age, marital status, etc

- this is a “binary classification” problem, where the model returns a 0 (the client is likely to payback the loan, and the bank will approve the loan) or 1 (the client is likely to default, and the bank will not approve the loan)

- first, we perform some data preparation

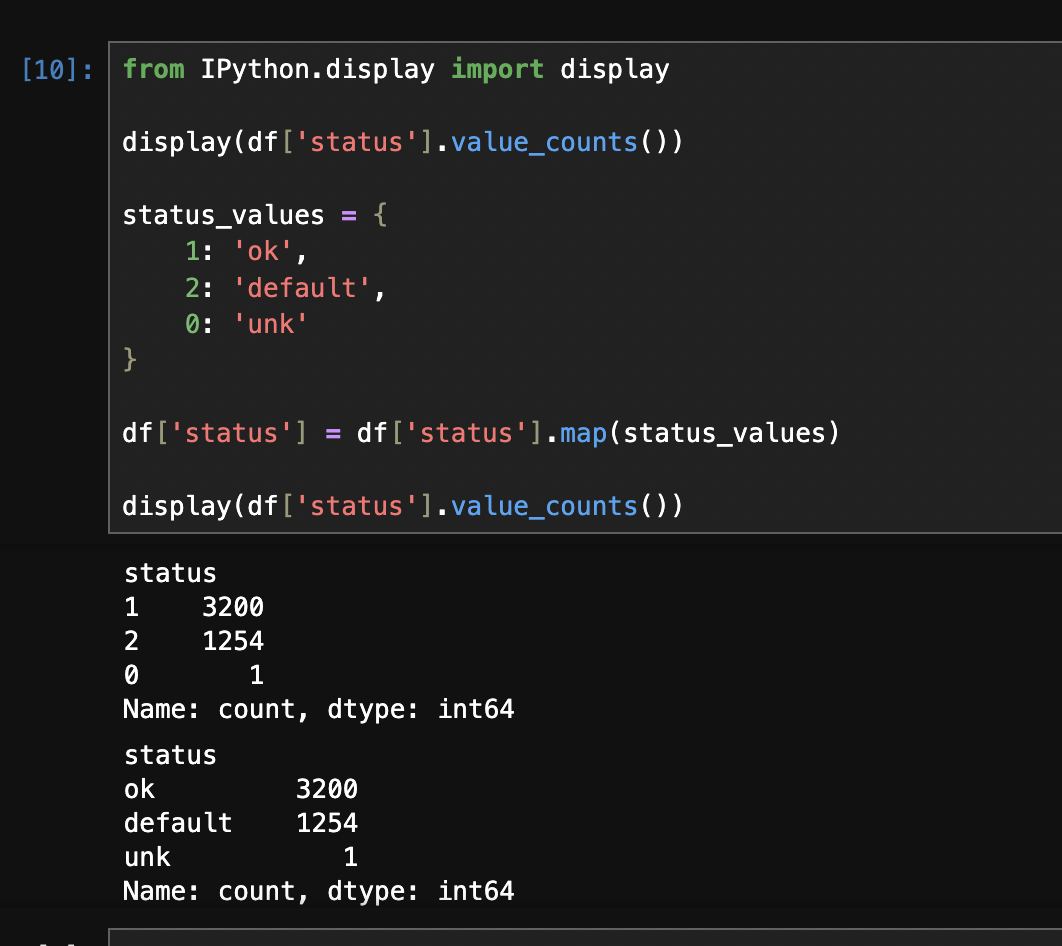

- we can use the following code to map numbers to strings for categorical features. i am guessing this is needed because it is for e.g. used by dict vectorizer. look at the before vs after of

value_counts -status_values = {

1: 'ok',

2: 'default',

0: 'unk'

}

df['status'] = df['status'].map(status_values)

- some columns have 99999999 for missing values. we can confirm this by running

df.describe(), as it shows the various stats of numerical columns. we can fix it as follows. after making this fix, we see how the various statistics like mean etc for these columns start making sense as well -df['income'] = df['income'].replace(99999999, np.nan)

- we can also fill them with 0s instead based on our judgement

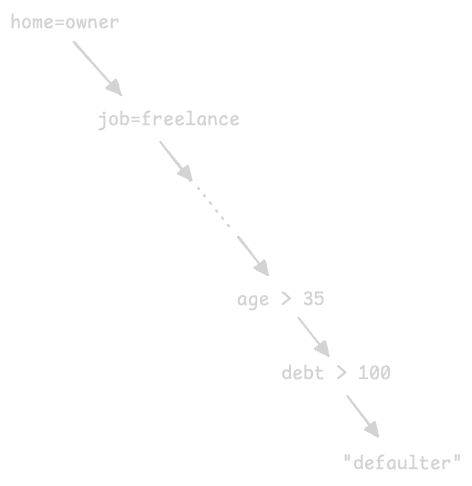

- “decision trees” - it has “nodes” which represent conditions (e.g. customer has assets with value > 5000), and the “branches”, which represent true or false. the records go through this tree from the root, until they reach the terminal node called “leaves”, which contain the value of the target variable

- these rules are learnt from the data - e.g if the customer has no past records of borrowing, and if they have no house, then they are a defaulter

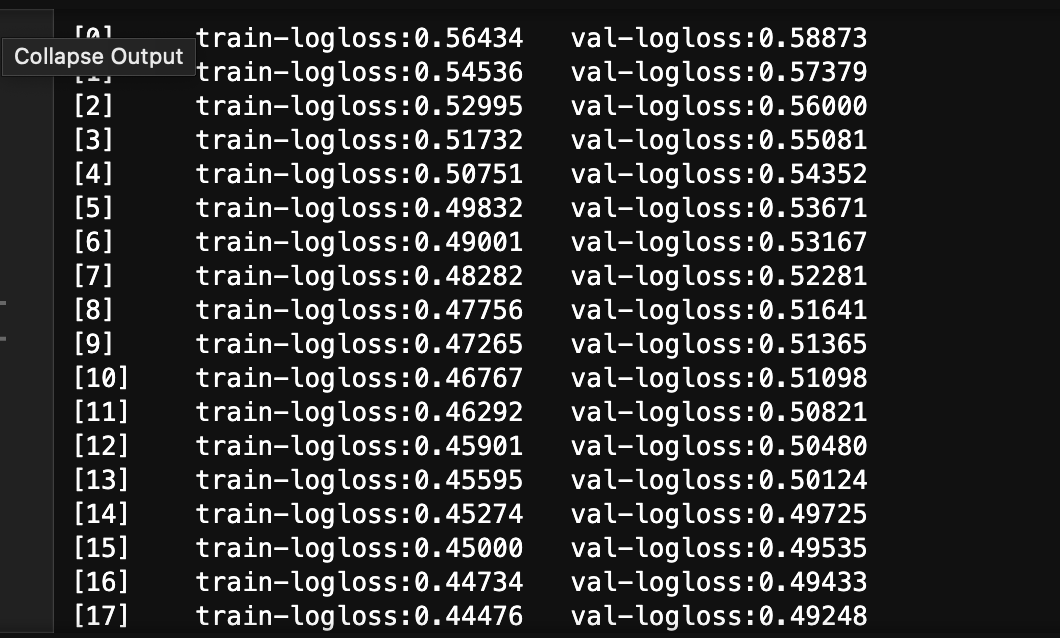

- using a decision tree classifier from scikit learn -

from sklearn.feature_extraction import DictVectorizer

from sklearn.metrics import roc_auc_score

dv = DictVectorizer(sparse=False)

dv.fit(train_dicts)

train_mat = dv.transform(train_dicts)

dtc = DecisionTreeClassifier()

dtc.fit(train_mat, train_y)

val_mat = dv.transform(val_dicts)

val_proba_y = dtc.predict_proba(val_mat)[:,1]

roc_auc_score(val_y, val_proba_y) # 0.654

train_proba_y = dtc.predict_proba(train_mat)[:,1]

roc_auc_score(train_y, train_proba_y) # 1.0

- so, 1 common problem with decision trees we see above - “overfitting”. we can see that auc for roc is 1 for the training dataset, but around 65% for the validation dataset. this is happening because our decision trees grow to large depths, thus memorizing the training data and failing when given the testing data. the leaf nodes then end up containing only 1 or 2 training data records

- so, we limit the depth of the tree, and we see that the scores improve automatically -

dtc = DecisionTreeClassifier(max_depth=3)

roc_auc_score(val_y, val_proba_y) # 0.7389079944782155

roc_auc_score(train_y, train_proba_y) # 0.7761016984958594

- we can visualize the decision tree as follows -

from sklearn.tree import export_text

print(export_text(dtc, feature_names=dv.get_feature_names_out()))

# |--- records=no <= 0.50

# | |--- seniority <= 6.50

# | | |--- amount <= 862.50

# | | | |--- seniority <= 0.50

# | | | | |--- class: 1

# | | | |--- seniority > 0.50

# | | | | |--- class: 0

# | | |--- amount > 862.50

# | | | |--- assets <= 8250.00

# | | | | |--- class: 1

# | | | |--- assets > 8250.00

# | | | | |--- class: 0

# | |--- seniority > 6.50

# | | |--- income <= 103.50

# | | | |--- assets <= 4500.00

# | | | | |--- class: 1

# | | | |--- assets > 4500.00

- how a decision tree learns - using “missclassification”. assume we have a condition for customers having assets > 3000 on the root node of the decision tree. this would split our data into two parts. however, the left part can have both defaulters and non-defaulters, and so can the right part

left_non_defaulters = (df[df['assets'] > 3000]['status'] == 'ok').sum() # 1776

left_defaulters = (df[df['assets'] > 3000]['status'] == 'default').sum() # 419

right_non_defaulters = (df[df['assets'] <= 3000]['status'] == 'ok').sum() # 1397

right_defaulters = (df[df['assets'] <= 3000]['status'] == 'default').sum() # 815

- so, “missclassification rate” for right part basically means, assume our model would have predicted “defaulter” for right part. what is the rate by which it would have failed? it would be 1397 / (815 + 1397) = 0.368 in this case

- then, say we can say take weighted average of left and right parts (weighted because for instance, no. of records on left can be more than right)

- we are basically trying to evaluate the “impurity” at the leaf nodes

- “missclassification” is a type of this impurity check for decision trees. however, we can use other metrics as well, e.g. “entropy” and “gini”

- “threshold” - while we hardcoded 3000, we would have to iterate for different possible values of this threshold, to “minimize the impurity”

- the pseudo algorithm for how decision trees work can be as follows (recall how we hardcoded a threshold of 3000, but that too can change) -

for all feature in features:

for all threshold in thresholds for feature:

split the dataset using feature > threshold

compute the impurity (e.g. missclassification rate) for the left and right parts

compute score using weighted average of the two halves

select the best (feature + threshold) combination with the lowest impurity

use it to split the dataset into left and right

- now, we keep applying this algorithm recursively to the left and right subtrees of our nodes

- the stopping criteria for this recursion can be -

- when the group is already pure / has reached a certain level of purity

- when the tree reaches the depth (we explored this earlier for overfitting)

- when the group size becomes too small to split into left and right. e.g. if we have 100 samples, it makes sense to run the algorithm, but it does not when the group size is say 5

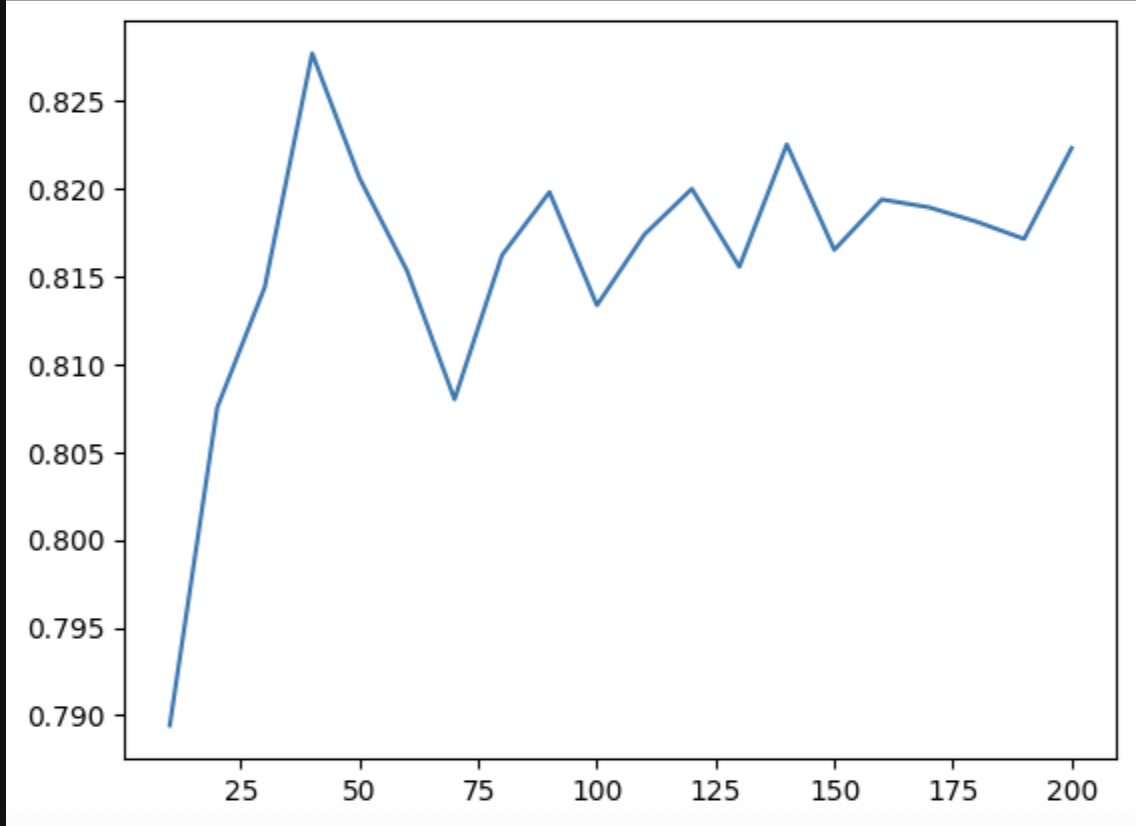

- so, we can now tune our model using the three parameters - “max depth” and “min samples leaf” (i.e. a node would be split only if it contains at least these many records)

for max_depth in [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]:

for min_samples_leaf in [1, 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50]:

dtc = DecisionTreeClassifier(max_depth=max_depth, min_samples_leaf=min_samples_leaf)

dtc.fit(train_mat, train_y)

val_proba_y = dtc.predict_proba(val_mat)[:,1]

score = roc_auc_score(val_y, val_proba_y)

print("%2d, %3d: %.3f" % (max_depth, min_samples_leaf, score))

- one technique in case of large datasets - to avoid the m*n loop, we first try finding the optimal subset of max depths first by setting a hard value for min sample leaf. then, we try finding the optimal value for min sample leaf using this subset of max depths that we obtained

- the lesser the depth of the tree, the more it tends to overfit

- note - while we only use it for classification here, decision trees can be used for regression as well

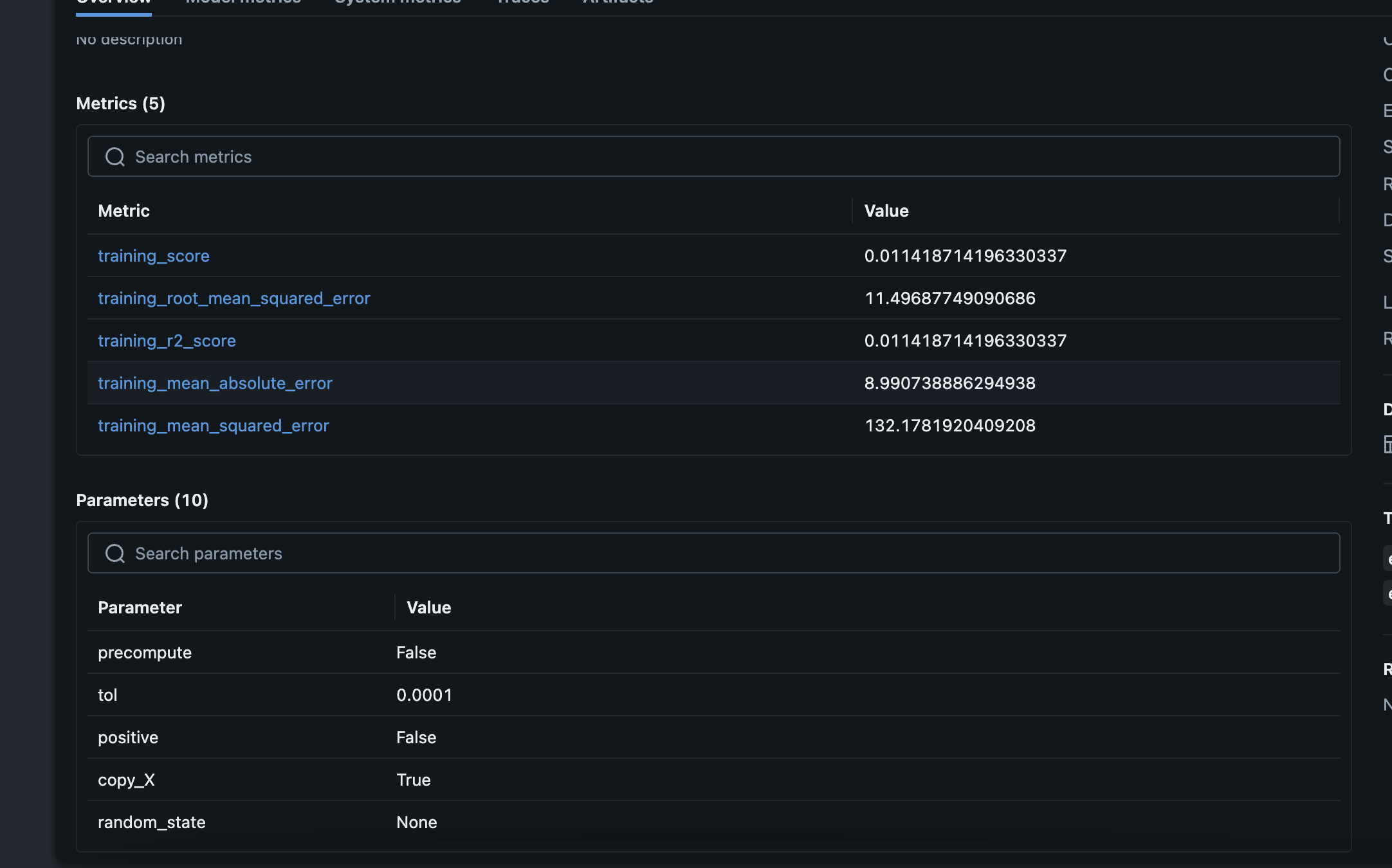

- assume we train a model as follows -

X, y = datasets.load_iris(return_X_y=True)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42

)

params = {

"solver": "lbfgs",

"max_iter": 1000,

"random_state": 8888,

}

lr = LogisticRegression(**params)

lr.fit(X_train, y_train)

y_pred = lr.predict(X_test)

accuracy = accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred)

- start a local server -

mlflow server --host 127.0.0.1 --port 8080 - in our code, we point to it as follows -

import mlflow

mlflow.set_tracking_uri(uri="http://localhost:8080")

mlflow.set_experiment("mlflow quickstart")

- we initiate a “run” that we will log the model and metadata to

with mlflow.start_run():

# ... rest everything comes here ...

- if we wrap everything around the

start_run block, what if some intermediate step has a failure? so, it is advised to have all the metrics, artifacts and models materialized prior to logging. this avoids unnecessary cleanup for partial runs later. which is why, the following code will all be wrapped inside start_run after we generate the model and metrics successfully - next, we log the model’s performance and metrics

mlflow.log_params(params)

mlflow.log_metric("accuracy", accuracy)

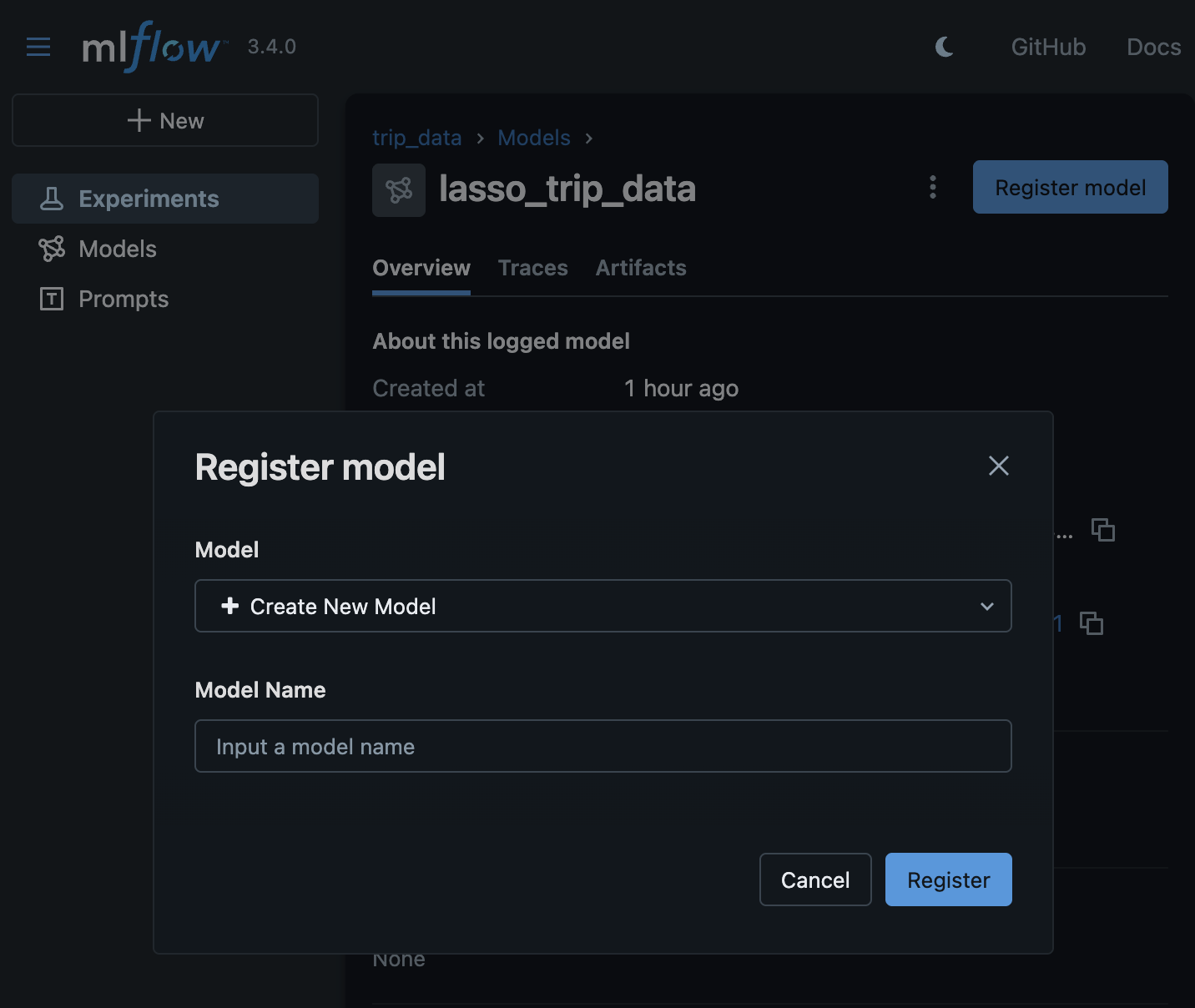

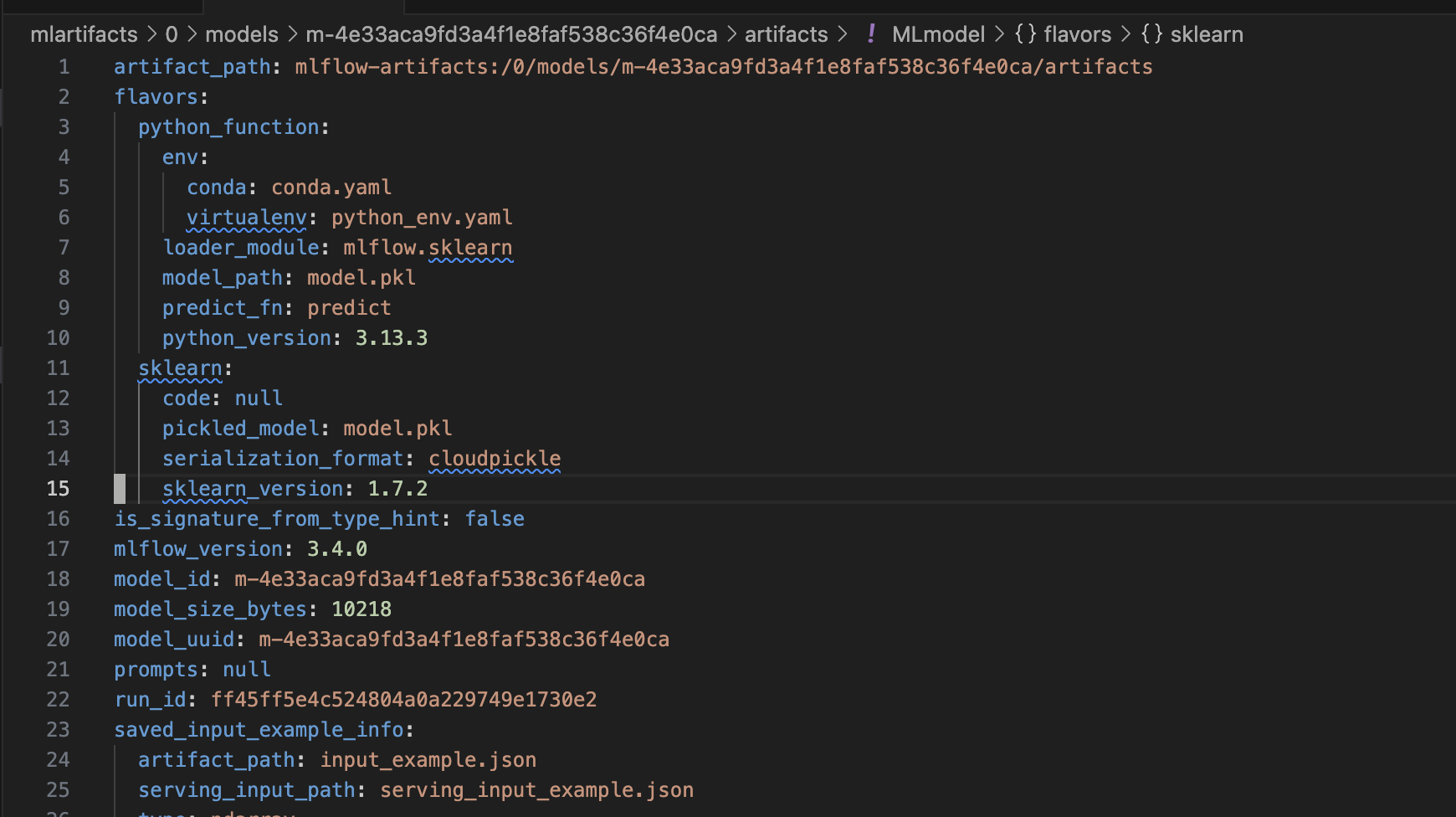

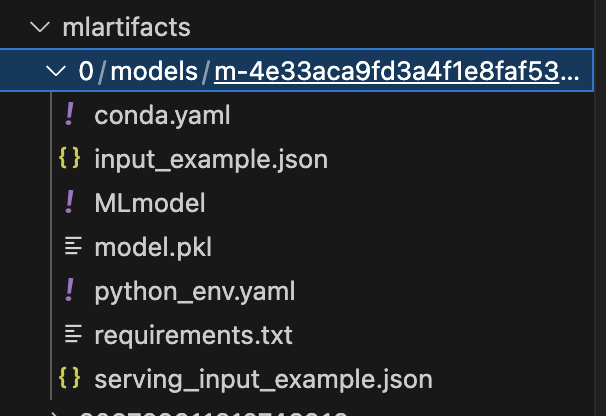

- we can “log” and “register” the model with mlflow’s model registry as follows. note how we also log the signature of the model -

signature = infer_signature(X_train, lr.predict(X_train))

model_info = mlflow.sklearn.log_model(

sk_model=lr,

name="iris_model",

signature=signature,

input_example=X_train,

registered_model_name="tracking-quickstart",

)

- we can tag the model as follows for easy retrieval later

mlflow.set_logged_model_tags(

model_info.model_id, {"Training Info": "Basic LR model for iris data"}

)

- now, we can load the model as a python function and use it for inference as follows -

loaded_model = mlflow.pyfunc.load_model(model_info.model_uri)

predictions = loaded_model.predict(X_test)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()