Physical Time

- we need time for various use cases in distributed systems -

- record when an event happened in logs, databases, etc

- when to expire things from cache

- measure performances, profiling, etc

- “physical clocks” - count no. of seconds, tell us the date and time, etc

- most computers use quartz crystal oscillators to keep track of time

- these oscillators vibrate at a constant frequency

- they use “piezoelectric effect” underneath. this basically means they generate an electric signal when mechanical stress is applied and vice versa

- since they are crystals, they are prone to error

- error is measured in “ppm” or “parts per million” - 1 ppm is 1 microsecond per second or 32 seconds in a year

- as a rule of thumb - most quartz clocks will have errors around below 50 ppm

- for a much more accurate clock, we can use “atomic clocks”

- it uses caesium (very expensive) or rubidium atoms (cheaper) underneath, but they are bulky in nature

- their precision is 1 second in 3 million years

- these clocks are what get used in gps etc underneath

- “gmt” or “greenwich mean time” - there is a line in the laboratory. when the sun falls on it, the time is noon gmt

- issue - we have two different ways of measuring time - quartz / atomic clocks (“quantum physics”) and earths rotation (“astronomical”)

- so, “utc” or “universal coordinated time” is used - it is based on atomic clocks but adjusted with earths rotation

- this “adjustment” is called “leap seconds”

- so every year on 30 june or 31 december, one of these three things may happen -

- a leap second may be added - clock jumps from 23:59:59 to 23:59:60 and then to 00:00:00

- a leap second may be removed - clock jumps from 23:59:58 to 00:00:00

- nothing may happen

- the two common ways to represent time in computers are -

- “unix time” - no. of seconds (epoch) since 1 january 1970

- “iso 8601” - e.g. 2025-12-26T14:28:56+00:00 - a human friendly format for year, month, day, hour, minute, second, timezone offset

- we can inter convert between these two formats easily

- however, computers ignore the leap seconds correction completely

- this was the issue on 30 june 2012, when there were issues across multiple systems because of the leap second addition

Clock Synchronization

- computers use quartz clocks, which are prone to “drift”

- solution - “clock synchronization” - periodically get the time from a more accurate source (e.g. atomic clocks)

- e.g. “ntp” or “network time protocol”

- we can see the ntp server configured for our macos devices under the settings for date and time

- “stratum” - clocks are arranged in a hierarchy

- “stratum 0” - atomic clocks

- “stratum 1” - directly connected to stratum 0 server

- “stratum 2” - connected to stratum 1 server

- uses strategies like querying multiple servers to remove outliers etc. with ntp and a good network, clocks can be synchronized to within a few milliseconds

- now, the client compares the time it has locally vs the time received from the server, and based on it, it makes one of the following decisions -

- “slewing” - used when the difference from server is less than 125ms. it slightly changes its clock speed by say 500 ppm for a few minutes to gradually sync up

- “stepping” - used when the difference from server is between 125ms and 1s. it immediately sets its clock to the server time i.e. there is a “jump” in the time

- “panic” - used when the difference from server is more than 1s. it raises an error and does not sync. it requires manual intervention

- e.g. because of the skew observed in the quartz crystal, the clock applies a slew of 500ppm to gradually bring the ntp server and the client in sync

- there are two kinds of clocks -

- “time of day clock” - both slewing and stepping are applied

- “monotonic clock” - only slewing is applied. so, it can only move forwards, never backwards

- issue with time of day clock - due to the stepping, the elapsed time can also be negative, or can be much bigger

long start = System.currentTimeMillis(); // some processing long end = System.currentTimeMillis(); long elapsed = end - start; - apart from the superficial difference of milliseconds vs nanoseconds, this api uses monotonic clocks instead

long start = System.nanoTime(); // some processing long end = System.nanoTime(); long elapsed = end - start; - time of day clock can measure epoch / tell us the exact date and time

- advantage - can be used to compare across nodes

- disadvantage - can move backwards because of stepping

- monotonic clock is an arbitrary clock e.g. time elapsed since the machine booted up

- advantage - can be used to measure elapsed time correctly

- disadvantage - do not have any meaning when compared across different machines

Causality

- assume the following scenario -

- node a sends a message to node b and node c

- node b sends a reply for this message to node a and node c

- node c might receive the reply from node b before the original message from node a

- this can happen because of network delays etc

- thus, the messages would not make sense to node c

- so, despite our efforts with clock synchronization, we are still unable to order events correctly in distributed systems

- so, we need “happens before relationship” in distributed systems

- we say a -> b (a happens before b) iff -

- a and b are events in the same process and a occurs before b

- a is the event of sending a message in one process and b is the event of receiving that message in another process (receiving can only happen after sending)

- there is an event c such that a -> c and c -> b (transitivity)

it is possible that neither a -> b nor b -> a. in that case, we say a b (a is concurrent with b) - this phenomenon is called “partial order” (as some events are incomparable)

- note - concurrent does not mean happening at the same time. it means there is no causal relationship between the two events

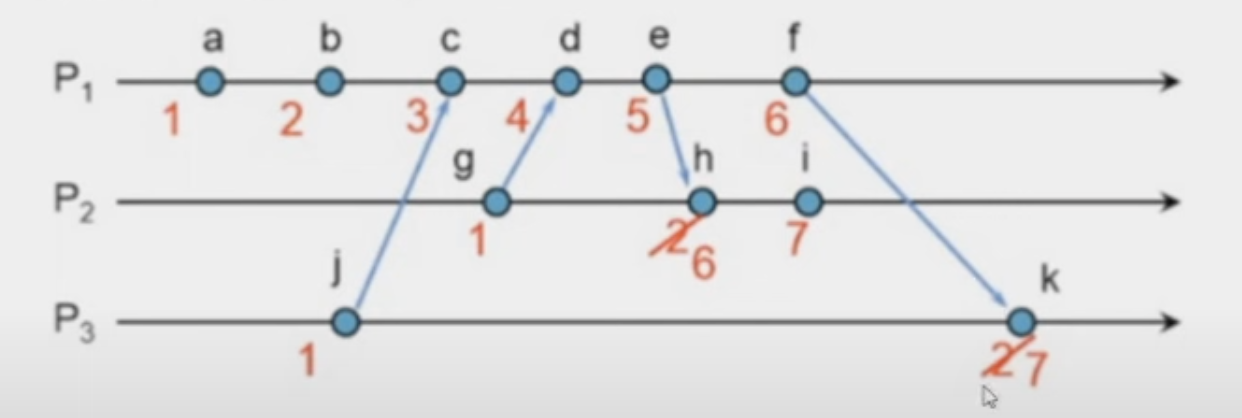

Example

- due to rule 1 - a -> b, c -> d, e -> f

- due to rule 2 - b -> c, d -> f

- due to rule 3 - a -> c, a -> d, a -> f, b -> d, b -> f, c -> f

a e, b e, c e, d e

Causality

- if a -> b, then a “might have caused” b

if a b, then a “cannot have caused” b - so, happens before encodes “potential causality”

Conclusion - Ordering Events

- our scenario’s problem was our inability to order events correctly in distributed systems

- we basically want to ensure the correct order of events in the distributed system

- if a -> b, then a should appear before b in that order

however, if a b, then a and b can appear in any order

Logical Time

- even with “clock synchronization”, physical clocks cannot help us with causality

- so, we use “logical clocks” to capture causality

- they use a counter for the number of events, and have no relation to the actual time

- we want our logical clocks to capture this accurately - if a -> b, then T(a) < T(b)

- two kinds of logical clocks - “lamport clocks” and “vector clocks”

Lamport Clocks

- initialize with 0 for each node

- on any local event on the node, do t = t + 1

- on sending a message -

- do t = t + 1

- send (t, m) i.e. attach the timestamp when sending the message

- on receiving a message (t’, m) - do t = max(t, t’) + 1

- issue with lamport clocks (my understanding) - it does not work across nodes

- in the above diagram, we cannot say for e.g. if j happened before a or vice versa or if they are concurrent

- so, we need vector clocks

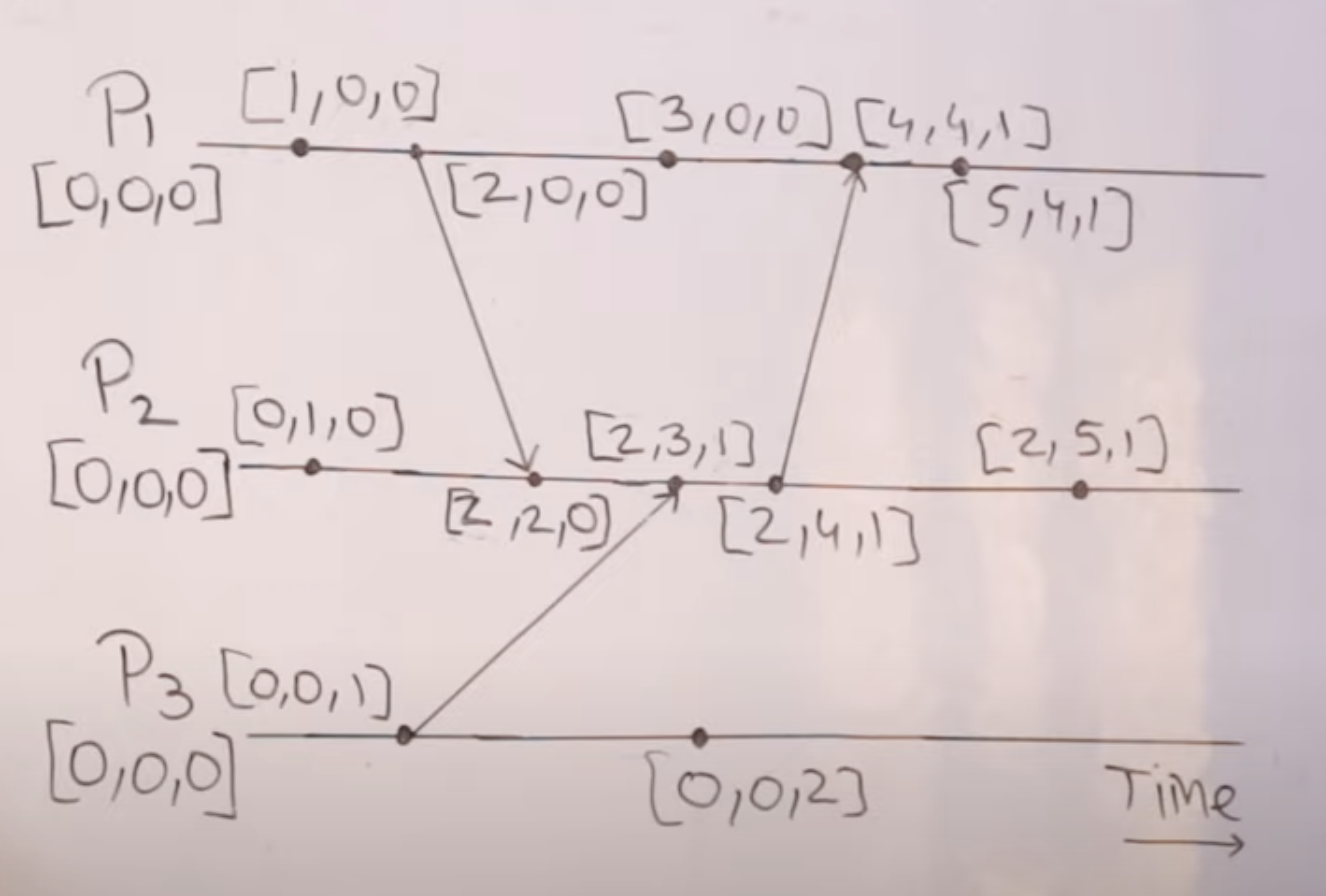

Vector Clocks

- initialize with (0, 0, … 0) for each node

- on any local event on the node, do t[i] = t[i] + 1

- on sending a message -

- do t[i] = t[i] + 1

- send (t, m) i.e. attach the timestamp when sending the message

- on receiving a message (t’, m) -

- do t[j] = max(t[j], t’[j]) for all j

- then, do t[i] = t[i] + 1

- now for e.g. 2,2,0 would represent not only this event

- but also all events that happened before it - e.g. 1,0,0, 2,0,0 and 0,1,0

- now, we have the following things -

- $T = T’ \iff \forall i, \; T[i] = T’[i]$

- $T \leq T’ \iff \forall i, \; T[i] \leq T’[i]$

- $T < T’ \iff T \leq T’ \; and \; T \neq T’$

- $T \parallel T’ \iff neither \; (T < T’) \; nor \; (T’ < T)$

- so, we can now accurately capture the “happens before” relationship -

- $V(a) < V(b) \implies a \to b$

- $V(a) \parallel V(b) \implies a \parallel b$

- vector clock disadvantage - vector clocks can become huge / difficult to store, and hence not fit inside the 64 bit space

Redis

Memcached

- it uses “shared nothing architecture”, which helps it with high throughput

- facebook uses memcached, as redis was not around back then

- there, out of 50 million requests, only 2.5 million reach the persistent storage, i.e. it has a cache hit rate of 95%

- now we discuss about redis, and how it differs from memcached

Features

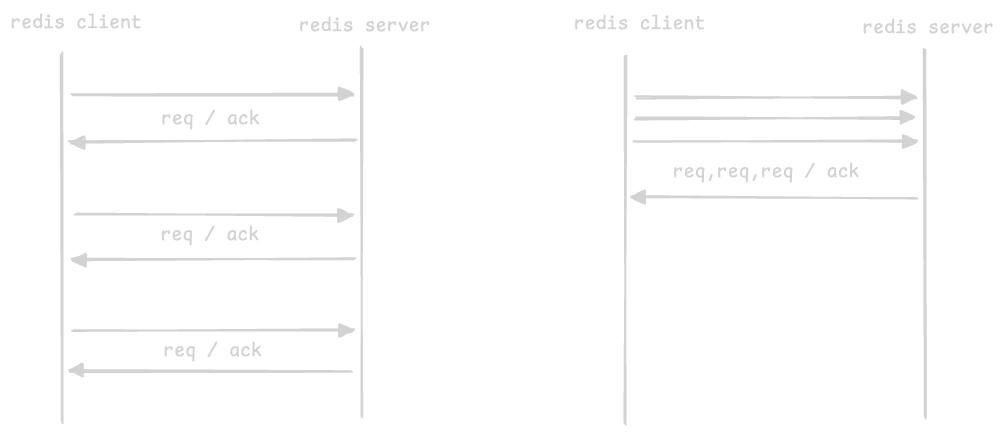

- “pipelining” in redis -

- redis uses “pipelining” to reduce the number of “rtt” or “round trip time” spans

- basically the client does not wait for every request’s response

- advantage - reduces time spent in socket io, context switching, etc

- the multiple requests are processed independently, e.g. one might return an error and another a success

- “data structures” in redis -

- in memcached, both key and values are stored as strings. so, values need to be serialized before storing / we cannot manipulate the values

- however, redis supports “data structure storage” instead of retrieving the data, manipulating it and finally storing it back, we can make in house changes

- it supports sorted sets, bitmaps, hashmaps, etc

- by using ram primarily, caches can easily use complex data structures like sorted sets, bitmaps, hashmaps, etc without worrying about how to store them

- “single threaded model” in redis -

- redis uses a single threaded model, thus avoiding complexities around context switching, locking, etc

- this is why some setups run multiple instances of redis on a single server to utilize multi core systems better

- since redis is single threaded, all operations performed on redis are atomic in nature

- memcached, however can efficiently use multi core system / multithreading unlike redis

- “persistence” in redis -

- it provides configurable persistence, which can help reconstruct the cache in case of restarts

- firstly, it periodically take snapshots and store dump files on the disk

- secondly, it can also log all operations to a wal file

- we can opt-in to these persistence mechanisms, or keep everything in memory only

- memcached uses ram only. it uses 3rd party tools for implementing non volatile storage

- “expiration policies” in redis -

- use the “expire” command manually

- set expire arguments in set commands (like ttl)

- supports managed eviction policies like lru

- writes happen via primary, which then go to secondary using wal files, similar to dynamodb

- sharding happens using the key we choose, so we should choose it wisely to avoid “hot partitions”

- one crude way to scale in redis - write the key to multiple servers (e.g. append random numbers multiple times to the key). now. we can then read it from any of the multiple servers we wrote to as well

- note - in redis, the “client” knows about all the servers, and routes the requests to the right server

- the servers are each aware of each other using the gossip protocol

Redis Streams

- this covers “streams” in redis, and its comparison with kafka

- think like kafka - but has some differences in how it works

- “redis stream” is basically a data structure - so it is basically the value part for a specific key

- its basically an “append only” log - we can only add data to it - this is much like kafka

- kafka writes to disk and uses os page caching. so, reads etc needs to be sequential

- however, redis is in memory first, but supports persistence using snapshots etc. so, reads are much faster. additionally, access can be much more random as well. however, it may not be as durable as kafka

- kafka achieves scaling by “partitioning” the topic

- to achieve the same in redis, recall that the stream is basically a value. so, we can have multiple streams instead (say data_stream_1 and data_stream_2). this are basically multiple key value pairs of redis, and since they are independent of each other, they can be present across multiple redis servers

- each “entry” in redis streams has three parts - an id (which is a combination of epoch and sequence number) and is also a key and value pair

- writing to a stream -

add <key_of_stream> <id> <key> <value>- id can be*for generate it automatically - reading from a stream -

read <key_of_stream> <id>- id can be$for reading from the end - specifying the id when reading is like specifying “offsets” in kafka

- we can use “range queries” on streams, since it is internally sorted by id (think bst)

- redis supports “consumer groups” like kafka, but the principle is different

- in kafka, the partitions are assigned to different consumers, so each consumer reads from its own partition

- however in redis, all consumers read from the same stream. recall how streams can be thought of as one partition of the kafka topic

- so, the consumer group in redis ensures that each entry in the stream is read by only one consumer in the group

- so, one advantage of this model - say in kafka, one of the consumer handles partition 1, and another handles partition 2. if consumer 1 is much faster, it would sit idle, while consumer 2 is doing its job. however in redis, since multiple consumers read from the same stream using consumer groups, the faster consumer can continue reading more entries

- if a consumer fails, other consumers can read the unacknowledged entries from it after a timeout. this is called “claiming” the entries

- one use case of redis streams - it can basically act as a “asynchronous job queue”

- a consumer group of multiple “workers” can keep consuming items from this stream

- if there is a failure in the worker, other workers can claim it after a timeout

- the guarantee here is “at least once” processing i.e. multiple workers might be assigned the same item in case of failures (e.g. a worker continues processing an item but crashes before acknowledging it)

Redis PubSub

- unlike redis streams, redis pubsub does not store messages durably in disk or in memory

- it has no overhead of offsets, consumer groups, etc

- it has at most once delivery semantics

- this is also called “fire and forget” model

- use case - it has much much higher throughput than redis streams because of this

Redis Sorted Sets

- example use case - leaderboard for top 5 tweets

- again, the sorted set is basically a data structure stored as the value for a specific key in redis

- each entry has two parts - “score” and “key”

- we can only have one entry for a specific key, and the set is sorted by “score”

- adding to the sorted set -

add <key_of_sorted_set> <score> <key> - so, we can add tweets based on id for key, and number if likes for score

- for updating the number of likes for a particular tweet, we can simply call the add command again with the new number of likes but the same tweet id (same key new score)

- we can do some complex operations - e.g. remove all but top 5 elements -

remove_by_rank <key_of_sorted_set> 0 -5 - adding the elements and maintaining the sorted list takes log(n) time, so keeping the n small by performing the above operation periodically keeps our performance fast

- again, to scale this, we need to have multiple sorted sets, as a sorted set is basically a value and lives on one node only. at the time of querying, we query all of them and merge the results to get the final top 5 tweets

- internally, it is implemented using a combination of “hashmaps” and “skip lists”

- hashmap - o(1) access to the “score” of a specific “key”

- skip list - like a bst, sorted by score. o(log n) insertion, deletion, etc

- another use case of sorted sets are “geospatial indices” i.e. they use sorted sets underneath

- it exposes a very easy to use api which we can leverage

- we can add locations like this -

geo_add <key_of_index> <longitude> <latitude> <identifier>. e.g. we add a bike to our inventory -geo_add bikes 77.5946 12.9716 bike_1 - then, we can query for members within a radius using -

geo_search <key_of_index> <longitude> <latitude> <radius> <unit>. e.g. we search for bikes within 1 km of a particular location -geo_search bikes 77.5946 12.9716 1 km - how it works underneath - a “geohash” is generated using the latitude and longitude, which is then used as the score in the sorted set. then, we are basically performing range queries on the sorted set

- i was thinking that if asked to scale it in interviews, we can for e.g. scale using specific areas i.e. one sorted set per area, as one sorted set lives on one node only